In the second of a 4 – part series on social sector spending in India, the Accountability Initiative in collaboration with Live Mint, looks at expenditure under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA). For a ready reckoner (image) click here. For a detailed analysis see the article – RTE fails to lift learning outcomes.

Archives: Blog

What are we reading – Feb 24th

This EPW article, of which our advisor Mr Raghunandan is a co-author, examines various issues concerning the accounting mechanism for Centrally-Sponsored Schemes and attempts to develop a comprehensive systemic solution to the problems. It requires an EPW login id and password.

This volume by Vikram K. Chand evaluates processes of change and reform in public service delivery in a range of states and sectors over the last decade. Demonstrating how reforms unfolded in a highly complex environment laden with uncertainty, it points to the importance of contextual factors in shaping reform choices as well as the role of leadership in fashioning strategies for change.

The draft of the “Redressal and Whistleblowers’ Protection Bills” proposed by NCPRI (Actually it is Whistleblower’s Protection Bill 2011 and The Right of Citizens for Time Bound Delivery of Goods and Services and Redressal of their Grievances Bill, 2011”…quite a mouthful isn’t it?). This particular webpage has a series of background documents on the above bills.

Decentralisation in India: Poverty, Politics and Panchayati Raj by Craig Johnson : This paper reviews the literature on Indian decentralization and assesses the extent to which the Indian States of Andhra Pradesh (AP) and Madhya Pradesh (MP) have devolved political, administrative and fiscal authority to local Panchayats.

The Annihilation of Caste by Dr. B.R Ambedkar – A classic piece

Report of the B.K.Chaturvedi Committee on Restructuring of Centrally Sponsored Schemes.

Thanks to Gayatri, Shailey, Adarsh and Laina for the suggestions.

Understanding Local Dynamics and Tracking Fraud/Corruption in NREGS

In a previous blog post, Yamini talked about the study on social audits[i]. It was for this study that I was in Andhra Pradesh from 5th Feb to 18th Feb. The study aims to analyse the efficacy of the social audits as a platform to capture the universe of complaints and whether it leads to effective grievance redressal.

We were a team of 12; 10 enumerators and 2 supervisors. We had to interview 4 categories of wage seekers from 8 villages. The four categories were

1 – Random wage seeker[ii],

2 – Wage seeker who attended a village/ mandal level social audit meeting,

3 – Wage seekers who worked at a fraudulent worksite, i.e., a worksite where monetary irregularities like inflated material records or work not completed but shown a completed in records or inflated measurement records have been identified during the social audits.

4 – Wage seekers whose names appear in the social audit reports.

My main purpose during the survey was to understand the local dynamics in a village and track frauds, i.e., understand how corruption occurs and identify the various ‘actors’ involved in it. Understanding the local village dynamics would help us in analyzing whether the social audits have been able to capture the universe of complaints and tracking frauds would give us a background context when looking at the grievance redressal system.

For understanding the local dynamics in a village, my strategy (if you can call it one) was to talk to different communities in the village. Caste dynamics, I found, played a major role in the allocation of work and (timely) payment of wages. If the Field Assistant (FA), an Employment guarantee scheme (EGS) staff who is responsible for allocating and supervising work at the village level, was from the OBC community then the non-OBC community wage seekers had a string of complaints regarding wages not being paid, work not being allocated, corruption etc against the FA. And, if the FA was from the SC community then the non SC community had complaints against the FA.

In my quest for understanding the dynamics of the village I came across an interesting aspect with respect to providing work. In Andhra Pradesh work is allocated to groups; if one wants to work under NREGS, he/she has to be part of a group. A group can be formed with a minimum of 5 members and has an upper limit of 30 members. There are two types of groups, the Shrama Shakti Sangam (SSS)[iii] groups and ‘temporary groups’. A SSS group membership is fixed. Anyone one not included in the SSS group will be added to the ‘temporary group’. The temporary group is flexible about changes within a group.

So how does this affect one’s chances of getting work? Work is allocated to a group only if the group has the capacity to complete the work. For example, in ‘silt work’ you need about 5-6 people to unearth soil, 3 people to load the soil onto a tractor and another 3 people to offload the soil from the tractor. So on the whole, the group should have at least 11-12 members to complete the assigned task. Group dynamics affects the number of people willing to work together. Problems are further escalated if the groups have been formed without consulting the wage seekers, especially if it is a SSS group. Ideally the groups, both SSS or temporary groups, must be formed only after consulting the wage seekers Thus the availability of group member willing to work together determines whether a group gets work or not.

My second goal of tracking frauds proved to be quite a challenge. The EGS staff was always on their guard when we talked to them as they thought that we were from the government doing an evaluation. But the advantage of this was that they did not refuse to talk to us. However, towards the end, we did catch a break with an FA who was candid enough to share his knowledge about fraud in NREGS.

The two most common types of fraud/complaints cutting across the villages we’ve surveyed were “benami names” and inflated records. “Benami names” is the term used to represent ghost workers, i.e., a wage seeker who is not working under NREGS but has been marked as ‘present’ (worked) in the muster roll/records. The wage seekers are pretty vocal about pointing out benami names during the social audit, though they will not say who is responsible for it. The general feeling among the wage seekers is “If I have worked so hard that the skin on my palm has ruptured, why should you get wages without working?”

With respect to inflated records, the most common complaint was the inflated number of tractor trips used for transporting soil. Soil is used to make the farm land fertile and it’s applied before the rains. De-jure, 2.5 cubic meters should be transported per trip. But to save fuel costs, tractor owners load more than the prescribed limit. So the basic estimation of ‘so many trips for so much soil’ does not hold. One way misappropriation happens is that the FA/TA may still use the 2.5 cubic meters per trip even though the tractor owner took fewer trips. And, from the ATR[iv] reports, most of the tractor owners are not concerned about the additional money drawn using their name. When I enquired about this type of misappropriation, the FAs maintained that the village social auditors do not verify the facts correctly and that the tractor owner or farmer might have forgotten the number of trips by the time the social audit is conducted.

Then, there are few unwritten rules followed at the village level for allocating soil to farmers which makes it difficult to track misappropriation during the social audits. If the farmer for whom soil has been sanctioned does not require it, he can give his share to another farmer, through either a written or an oral statement to the FA. In some cases the sarpanch/panchayat orders the FA to give soil to an unsanctioned farmer.

Apart from caste dynamics, local politics influences the implementation of NREGS. Due to local political interference, many of the villages we visited did not have a village level social audit meeting during round 2 and round 3 social audits. The social audit staff I spoke said that when there is a threat from the local influential/political people in the village, they don’t conduct the village level audit meeting or they conduct the village level audit meeting but don’t read out all the complaints.

These issues however have been addressed in the 4th round of the survey. From the 4th round onwards, the Mandal Revenue Officer (MRO) is mandated take part in the village level social audit meeting as an independent observer. This means that there would be added security at the village level audit meeting and the presence of a higher official at the audit meeting gives a sense of security to the audit team. The presence of the MRO also increases the probability of issues getting resolved at the village audit meeting.

Another new feature that would strengthen the social audit process is the introduction of ‘Mobile Courts’. Based on the quantum of misappropriation, mobile courts would be available at selected villages after the mandal level public meeting. The main purpose of the mobile courts is to facilitate the follow up of the complaints registered at the village and mandal level social audit meetings.

On the whole, the EGS staffs are of the opinion that Social audits have a positive impact. Because of social audits there is a fear among the EGS staff of being embarrassed in front of the village if involved in corruption/fraud. Though they have complaints against round 2 and round 3 social audits, they feel that

[i] Click here for more information about social audits

[ii] Beneficiaries of NREGS.

[iii] Shrama Shakti Sangam, a Self help group of 20 to 30 members formed by the government of AP

[iv] Action Taken Report; a report stating the action to be taken on various complaints as decided in the

mandal level social audit meeting

What are we reading? – Feb 17th

The New York City Charter Schools Evaluation project analyzes the achievement of 93 percent of the New York City Charter school students who were enrolled in test-taking grades (grades 3 through 12) in 2000-01 through 2007-08. The technical report, accessible here, which describes the methodology of assessment is what has interested our researchers

The Justice Select Committee in the United Kingdom has scheduled its first “evidence session” on possible revision of the Freedom of Information law. This Guardian article talks about the Information Commisioner, Christopher Graham’s response to requests for repealing the law.

A simple idea on linking financial literacy and education by Stephen J. Dubner on the ever-popular Freakonomics blog

Does linking teacher pay to performance work? – An evaluation by Karthik Muralidharan and Venkatesh Sundararaman which aims to contributes to the debate on the relative effectiveness of input-based versus incentive-based policies in improving the quality of schools. The study involved a randomized evaluation of a teacher performance pay program implemented in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh (AP).

A Freedom of Information blog-post on the order of the India Central Information Commission telling the Ministry of Environment & Forests to put more information on its website.

An incisive commentary by Paul Krugman on how morality and money is connected, and how the US should keep its focus steady on inequality, instead of focusing attention on the so-called declining moral values.

Daniel Schuman at the Sunlight Foundation has come up with benchmarks to measure success in making legislative data available online.

An interesting book which examines identities, violence and conflict in the context of internal migration within India. The second volume in this annual series, India Migration Report 2011 focuses on the implications of internal migration, livelihood strategies, recruitment processes, and development and policy concerns in critically reviewing the existing institutional framework.

An interesting debate – Surjit Bhalla in an Indian Express column tried to measure corruption by looking at NREGA performance. Martin Ravallion in this EPW paper, responds to Bhalla’s comments.

Thanks to Shailey, Gayatri, Ambrish, Indrojit, Yamini and Laina for this week’s list.

Rants of a Public Finance Junkie

For the past few months, my colleague and I had been holed up at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), trying to “uncover” the wonderful world of state budgets. Our task appeared to be simple – we wanted to categorise the elementary education budget for various states into more accessible and functional categories, thereby enabling us to estimate the “cost” of various inputs in delivering elementary education. This would further allow us to compare differing state priorities on the basis of the “type” of allocations/ expenditures. So for instance, since we were working on education, the categories consisted of:-

- School Infrastructure

- Teacher salaries,

- Teacher inputs (such as training, materials etc),

- Entitlements for children such as uniforms, textbooks etc,

- Mainstreaming of children (out of school etc),

- “Quality” related inputs and,

- Administration.

Did I say simple? Umm… not so much. Let me explain.

The existing system of classification divides the Consolidated Fund of India (namely, the fund from which all expenditures of the Government are incurred into Revenue and Capital Sections (for more details on revenue and capital expenditure please see here) and requires that all expenditures be categorized into these two broad divisions at the highest level. At the operational level, all allocations and expenditures are classified using a 6 tier hierarchical classification. These are:-

| Classification | Type of Classification |

| Major Head | Represents the major functions of the government |

| Sub-Major Head | Represents the sub-functions of the government |

| Minor Head | Refers to government programmes |

| Sub-Head | Schemes of the government |

| Detailed Head | Representing sub-schemes |

| Object Head | The economic “type” of expenditure |

Thus for example in education, if we wanted to know the amount of money being allocated for the Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) providing grants in aid to SCERT for teacher training institutions, we would have to drill down from:-

2202- General Education (Major Head)

01 – Elementary Education (Sub-Major Head)

001- Teacher Training (Minor Head)

85- Teacher Training Institution

99- Grants in aid to SCERT

31- Grants in aid to SCERT (CSS)

(for more details on Minor Heads and Major Heads, please see here)

OK, now having detailed the task at hand, let’s get to the problems (this is going to be a long list). So reader patience is advised.

1) Logistical

One of the first (though probably the least important given the list!) is the sheer logistics of looking at state budgets. Many states do not have their budgets online, or if they do the links don’t always work, and past years’ budgets are unavailable. Moreover, often while the overall budget is available, the “detailed demand for grants” (necessary for disaggregation) is not. The task thus requires access to a library such as NIPFP and a LOT of manual data entry! Moreover, the sheer volume of budgets (some states have 9 volumes) results in a lot of heavy lifting! Further, some budgets are only in Hindi, which makes it difficult for those whose vernacular is not Hindi to access such documents

2) Lack of Uniform Accounting systems

a. Differing Budget Heads:

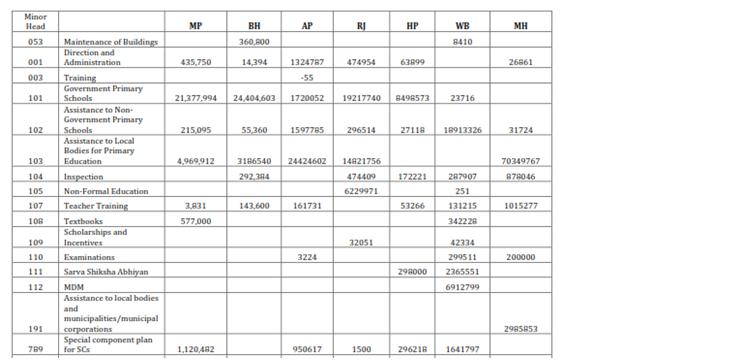

Under the current system of classification, functions not only repeat themselves under revenue and capital sections but more importantly, there is no uniformity of classification in terms of budget heads across states. A look at the table below containing collated information for 2008-09 indicates the basic problem. For each state, allocations are booked under different budget heads. To give an example, while Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan should technically be a sub-minor head (as it is a scheme), it is sometimes included as a minor head (a government programme). As a result, while Himachal Pradesh and West Bengal give SSA separately as a minor head (111), for other states it comes as a sub-minor head under government primary schools (101). Similarly, for some states such as Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal, textbooks have been mentioned separately, it does not mean that other states do not provide textbooks. The truth is that in other states it is booked under a detailed head.

Source: Compiled from the Comptroller and Auditor General, State Finance Reports. Numbers are provisional.

b. Functional Categories not always “functional”

As the recently released Rangarajan Committee Report (see here) – (a must read for those interested in public finance) aptly recognises, “functional heads should be really functional” – though that is often not the case. For instance, a major head like 2552 (North Eastern Areas), does not really signify any “function” of the government and even expenditure on education in North Eastern Areas is shown under this head. As such, as the report highlights “This is a geographical attribute camouflaged as functional attribute”, increasing the difficulty in classifying budgets.

c. Lack of Uniform Measurement units

Related to the lack of uniform budget heads is the lack of uniform units of measurement. While some states report in lakhs, others in crores, others in thousands, some states such as West Bengal report actual numbers. Collating these in itself becomes a cumbersome process and requires us to have our 0’s in order!

d. Decoding some of the Budget Heads

A further complication caused by the lack of uniform budget heads was the fact that often the detailed object heads were missing, resulting significant problems with decoding the budget heads. For instance, a budget head such as “Assistance to local bodies” consists broadly of monies provided to Gram Panchayats etc for the delivery of education. Within it, however there would be components of salaries, administrative expenditure, maintenance works, inspection, and even actual schools built by the Zilla Parishad.

3) Dealing with Multiple Departments or Budget heads other than 2202.01

While some states, such as Karnataka and Rajasthan classify their budgets only according to budget heads, for most states it is done department wise. An example below:

One would imagine that education would be under the Department of Education. Unfortunately, that is not necessarily true. State governments also draw funds from the Tribal Welfare Department, Social Welfare and Justice Department, the Planning Department and Public Works Department amongst others. While some states book grants from Tribal Department and Social Welfare Department within 2202.01 as Tribal Area Sub-Plan and Special Component Plan for Scheduled Castes, others would require going through each and every department within the state budget. For instance, a state such as Chhattisgarh had the education budget head in 14 different departments , while in Maharashtra, the planning department gives elementary education for each district (35 of them) separately!

In other cases, within the department of education itself, other budget heads such as 2059 (public works), 2225 (welfare of SCs), 2235(welfare of STs etc) are included further complicating the collating system.

Given the current push for accountability and transparency, it is surprising that detailed state budgets continue to be inaccessible to most. It is no wonder that for many (including me!), understanding and more importantly analyzing them remains an extremely daunting task. While, initiatives such as the the RBI’s annual State Finances –A Study of Budgets by the RBI (link here) are commendable, they still do not give the disaggregation required for us public finance junkies !

I am happy to report that we managed to task at hand, at least for the 7 states we were studying (For a look at the results, please look here), and since we are gluttons for punishment, we hope soon to do similar classifications for more states and even more sectors. Wish us luck (and sanity)!

What are we reading? – Feb 10th

Here is this week’s reading list. Hope you enjoy reading the articles and watching the videos!

- Improving governance through Budget Transparency: Twenty years ago hardly any organizations focused on budget transparency as a key to improving democratic accountability and improving outcomes for poor. Now, over 200 groups in at least 119 countries engage in such work. An interesting Huffington post which talks about improving governance through budget transparency.

- A report on State Budgets Transparency by CBGA. As the report says, the total expenditure incurred from the State Budgets accounts for more than half of the Total Public Expenditure in the country. That’s quite a strong case for State Budget Transparency!

- School autonomy and accountability go together – A very interesting World Bank blog which makes the case for school autonomy

- An interesting blog by Diane Spears from Rice Institute on whether India’s Total Sanitation Campaign improving Children’s health?

- How do we combat obesity? According to Dan Ariely, giving nutritional information alone to people has not helped people make better choices. An interesting research by him gives an alternative.

- The loo that saves lives in Liberia – The title says it all

- An old article on how we need a wikipedia for data. The discussion on HackerNews on this article is most interesting.

- A Delloite report on “Unlocking Growth – How open data creates new opportunities for the UK”

- Project updates on Wipro’s “Applying thought in schools” initiative.

- An interesting article by Ajay Shah on the Joint Entrance Examination for IIT’s and the economics behind it.

Procurement Policies under SSA

There is something to the way the government functions. It might not always be clear and transparent, or accountable for that matter, but it seems that there is the proverbial ‘order to the madness’. Emblematic of these order-inducing impulses, are documents known as Manuals. Manuals are essentially guidelines which are issued to constrain and determine government action (or inaction). In my quest to understand the inner workings of the government, I have perused through several of these guiding documents. My current favourite is the Financial Management and Procurement Manual[1] for the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA). Specifically, I’ve been focussing on the section on procurement.

According to the Manual, the procurement of goods and works for the implementation of SSA is supposed to take place at five levels: 1) School/community; b) BRC/CRC; c) District-level; d) State-level; and e) National-level. School-level procurement relates to the purchase of material for the repair and maintenance of the school, school equipment (e.g. drinking water facilities, blackboard), and teaching learning material (e.g. Charts, globes). Block-level procurement includes the procurement of items for the functioning of the Block Office. Items required at the school level are typically not purchased at this level, as procurement is done from the grants disbursed to the Block Office for their own expenditure. In contrast, District and State-level procurement includes items which are required by schools. Such items include textbooks, specialized kits for pre-school children, teaching aids for improving the quality of education, and other requirements for disabled children. Given that many of these items have design specifications and need to be purchased in bulk, procurement of these items has been assigned to the District and the State.

Items are procured either through tenders[2] or with the help of communities. In addition, under SSA, it is mandatory for all civil works relating to school construction to be conducted through community participation, that is, with the involvement of School Management Committees (SMCs)/ Gram Panchayat-level bodies etc. In carrying out this responsibility, SMCs can either carry out the work directly or by organizing workers from their community. Thus, SMCs have been not only been given the responsibility for procuring goods for schools, but provisions have also been made to ensure their involvement in carrying out the construction of civil works.

In a sense then, by restoring such responsibility to the community, the Manual asserts the importance of ensuring that procurement of goods is conducted through a decentralized process. However, while the manual places such an emphasis, it is interesting to see that at the ground level the autonomy enjoyed by the community to procure goods is not as extensive. During an intervention exercise that was conducted by Accountability Initiative and Pratham-Andhra Pradesh in partnership with the District Administration of Hyderabad, to assist schools in the making of their School Development Plans[3], we found that while in theory the SMC may have the responsibility for determining school-level expenditure, SMC resolution is often insufficient to procure material required for meeting school level needs. For instance, for the permission of desks and chairs, school’s reported that they were required to take permission from the State Implementing Society (body responsible for implementing SSA in the State). Further, even for conducting roof repair work, the SMC is required to take permission from the Junior Engineer, who typically needs to inspect the work and approve the plans before the work can begin.

Thus, while the guidelines may imply one thing, the ground level realities seem to paint a different picture. The picture, however, may not be as skewed. Permissions are often necessary for checking against inefficiencies in spending. Nevertheless, the fact that the SMC resolution is often not enough to determine procurement has an effect on the Committee’s capacity to both plan and meet school needs in a timely manner.

So where does this leave us? Probably in the unenviable position of having more questions than answers. In our future work, we intend to investigate precisely these issues by mapping the de-jure and de-facto procurement policies and investigating their implication for school level planning.

[1] For Details see: http://ssa.nic.in/financial-management/manual-on-financial-management-and-procurement

[2] The manual prescribes three types of tenders, 1) open tender, 2) limited tender and 3) single tender. For more details see-

[3] Under Section 22(1) of the RTE, schools are required to prepare a School development plan. The school development plans contain the list of prioritized activities to be undertaken at the school level.

Do regular citizen-led efforts to demand accountability from government result in systemic changes in service delivery?

Do repeated, regular social audits make a difference? Put a different way, do regular citizen-led efforts to demand accountability from government result in systemic changes in service delivery? Three Accountability Initiative researchers, landed in Hyderabad last night in pursuit of answers to this fundamental, yet complex research question. We hope to find our answers through a qualitiative research study where we will interview participants of social audits along with government officials to gather their perspectives on the effectiveness of successive social audits in Andhra Pradesh.

For the uninitiated, social audits, first evolved by the Mazdooor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), are a process by which citizens review and monitor government actions on the ground, and use findings from these reviews to demand accountability from government through the mechanism of a public hearing or Jansunwai. At the hearings, aggrieved citizens place their testimonies in the public domain and government officials are invited to respond to these testimonies and answer questions. The MKSS first experimented with social audits in the mid 1990’s.

In 2005, the Indian Parliament passed the National Rural employment Guarantee Act, now renamed the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), amidst widespread concerns about corruption. Social audits were introduced within the Act as a key mechanism through which corruption would be monitored and checked. According to the Act, social audits must be conducted every six months by the Gram Sabha. Unsurprisingly, there is a vast gap between the law and reality and most parts of the country are yet to implement these audits with one exception, the state of Andhra Pradesh. Consequence of a unique political environment and a rural development (RD) secretary who was keen to find innovative solutions to problems of corruption, Andhra Pradesh took the social audit provision seriously and actually set up an institutional mechanism to carry out social audits. The state now has a social audit society called the Society for Social Audits Accountability and Transparency under the RD department. Since 2006, when the NREGA was launched in the state, as many as 1,736 social audits have been conducted across the state.

Just about the time that the social audits were being initiated, I joined a team of researchers to try and understand the effects of the audits. Since those were early days, we primarily focused on the effects of the audits on people’s awareness about their rights and entitlements under the NREGA. We undertook a 6 month study where we visited over 800 NREGA beneficiaries 3 times over an 8 month period. – once before the social audit, then one month after the audit and finally 6 months after the audit. The findings were unanimous: the audits made a significant difference to raising awareness levels. We also found a few (albeit statistically less significant than the awareness data) improvements in the implementation of the MGNREGA related particularly to wage payments. Crucially, we found that the social audit had some effect on building people’s confidence to question the government and approach officials to resolve their problems. (If you are interested, details of the study can be found on the following link.

Although the study was completed in 2007-08, I had caught the social audit bug. However, as fascinated as I was with this effort at mobilizing citizens (some of the Andhra audits are attended in 1,000’s), I was always left wondering what happens after? Once the noise has died down, does an audit of this nature create enough disincentives to prevent malpractice? From a citizens perspective, once you’ve spoken at an audit and placed your testimony, does government respond and if so, does this ensure that citizens get their rights? In other words, do audits lead to systemic improvements in service delivery and perhaps most important, does this help reduce corruption? These questions have become even more critical in recent years as social audits have now entered the government nomenclature as the appropriate solution to all corruption problems. Having written a few papers on the subject, I find myself being invited on an almost regular basis to government meetings of different departments to talk to them about doing social audits for their various schemes. Of course no one has given any thought to whether the social audit is the appropriate tool or not, it’s now become the accepted solution!

And so, I made my way back to AP in March last year to try and get answers to my question. A lot has changed between 2007 and 2011. The audits have become institutionalized (and almost bureacratized) and to ensure follow up action the RD department has even set up an extensive grievance redressal system. Impressive to say the least! But on looking closely at the data, new questions emerged. My colleagues Sowmya Kapoor and Salimah Samji and I explored social audit data for 3 rounds of audits across 13 districts in the state to find that despite regular audits there has been little change in the nature of complaints (i.e. the nature of corruption) and the officials implicated through the social audits. The same type of official (invariably the field assistant who is responsible for managing the worksite, the branch post master who handles wage payments and the technical assistant or engineer who sanctions works and measures the sites) seem to be indulging in malpractice and inefficiencies, undeterred by social audits. To me, this suggests that there is something specific to the incentive structure of these official posts that encourages such activities, something that social audits have not been able to resolve (for details see this following paper).

And so we asked the obvious question – is this because of ineffective grievance redressal? Or is this a consequence of the very structure of the state at the local level?

To explore these questions, we are now in Hyderabad. The plan is to undertake a detailed qualitative analysis in 10 villages spread across 2 Mandals (blocks) in Medak district (we chose Medak because we have already done significant field work here). In each of these villages, we will identify (through the social audit reports) beneficiaries who complained or expressed a grievance during the social audit and follow what happened after. We will also interview a sample of local officials – those in decision making positions and those who have been implicated in the audits (these would include officials who have been fired or asked to pay money back to beneficiaries in the event of being caught red handed).

My own hunch is that we will find that while social audits are a critical space for strengthening democratic action and creating the relevant pressure points for change, their effectiveness is constrained by structural failures within the state. It is these structural failures that make it difficult for the system ro resovle complaints that emerge from social audits and create disincentives for malpractice. Effective administrative reform is essential and the key ingredient that needs to be mixed in with social audits if we want to see change. Will our field work bare this out? Watch this space for further updates.

What are we reading?

Here is this week’s reading list. Hope you enjoy!

- Olivier De Schutter, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food speaking about why we need to unite food movements.

- Karthik Muralidharan on the challenges and opportunities for Achieving Quality Universal Primary Education in India

- Report of the High Level Expert Committee on Efficient Management of Public Expenditure (Rangarajan Committee report)

- Rukmini Banerji on NDTV speaking on the topic of “Sarkari Schools: Padhna Hai Bhool?“

- Second Administrative Reforms Commission first report on “Right to Information: Master Key to Good Governance“

- Putting Government Data online by Tim Berners Lee: Introduces the idea of linked data and answers very briefly the question of “If you want to put government data online, what should you do”

- More unequal than others by Pranab Bardhan : He creates holes in the argument that everyone has an equal chance in a democracy when in fact there are a number of invisible factors that make sure the rich perform better.

- School Choice – videos – A collection of really interesting videos on education

- Guardian article: Sierra Leone launches online mining database to increase transparency

- Understanding Poverty : This volume brings together twenty-eight essays by some of the world leaders in the field of economics, who were invited to tell the lay reader about the most important things they have learnt from their research that relate to poverty.

Citizen Accountability

A few months ago I attended the launch of Rohini Nilekani’s latest book, ‘Uncommon Ground’, in which she brings a selection of the country’s leading industrialists and social activists together to “explore the middle ground between the ideological divisions that often polarise the business and voluntary sectors”, and deals with questions such as why, despite decades of liberalisation, does economic prosperity with social inclusion remain a distant goal. The event consisted of a panel discussion chaired by Nilekani with guest speakers Nikhil Dey and Gautam Thapur[1] [2]. The former played a major role in the introduction of the Right to Information Act and the latter currently runs a private corporation which provides goods and services from power generation and distribution to the manufacture of paper and pulp.

My interest in this conversation was in the views of the bazaar (businesses) and the samaaj (citizens) represented by Thapur and Dey respectively. I was curious to hear their suggestions about how the two should interact and the most appropriate ways for citizens to hold businesses accountable. To this end, there were three sets of comments that stood out for me. First, the importance of accountability mechanisms considering the sources of India’s recent growth; second, the need for such mechanisms considering changes to the demands of citizens; and third, the implications for citizens themselves.

My first reflection was triggered by Thapur’s suggestion that over the last 20 years, India’s growth has been predominantly built upon 3 sources – natural resources, land and licensed businesses – the first two of which are extremely public in nature and intrinsic to the livelihood of numerous communities. Dey pointed out how the development of these sources can be particularly contentious due to the fact that for many in India land is one of the precious few things they own or have a sense of belonging to. Consequently, any sudden or insensitive appropriation of land and/or resources from citizens often unsettles communities and breaks important bonds that have existed for generations, effects which are extremely difficult to place a value on. If Thapur and Dey are right, their points underline the need for appropriate transparency mechanisms between citizens and businesses. If India is to grow in a way that fosters social inclusion, proper mechanisms for highlighting and addressing negative externalities and impacts on society of business decisions need to be in place.

The second (and related) set of comments that struck me relates to how the demands of citizens have changed over the years. Specifically, the panel considered the increasingly active role played by social sector and non-governmental organisations as well as the readiness of public and press to protest and campaign. Dey offered a simplified explanation of the social inclusion problem in relation to businesses, that while the government exists to serve the interests of the public, it can come across as more consistently serving the interests of the private sector. Thapur recognised this perception but felt any such negative impacts were being increasingly mitigated because, in his view, people no longer tolerate being told what to do and increasingly want to be consulted.

Thapur’s view is encouraging for those working to strengthen participatory democracy. Indeed, in India, attention over the past few years has focussed on strengthening consultative processes with respect to the government. But the wider implication of Thapur’s suggestion is that there is scope for private enterprise to play a greater role in the shaping of communities if planning processes were stronger (ie. the way local governments decide about business ventures in their areas). The UK, for example, has successfully done this under the Section 106 Agreement in the Town and Country Planning Act (1990) which is used by local councils as a requirement of developers of large developments. It involves public consultation, an assessment of the social and economic costs and benefits and a needs assessment to ensure the benefits are maximised for the community. This way, an official consultative process acts as a check against business decisions.

My last point is more of an observation than a comment on what was said. Throughout the discussion, there was an implicit assumption that what was required was for citizens to be able to hold either the government and/or businesses accountable so that social inclusion could be brought about. But what about citizens themselves? Don’t the public yearn for cheaper and cheaper goods and services? Don’t we want things to be faster, more accessible, more premium but low cost? And is our sense of civic responsibility developed enough to consistently make socially considered purchasing decisions? After all, I was under the impression that market mechanisms respond to demand. Hence, if we demanded goods and services that fulfilled certain social criteria – as is happening in the markets for fair trade coffee and chocolate – wouldn’t the market be forced to provide these?

Thapur’s response to my question was clear – it was not necessarily the case that business decisions that accounted for social impacts led to increased cost and hence, higher prices for consumers. Basically, we can have both. And Dey was quick to admonish those consumers who favour low prices at the cost of social decision making, pointing out the irony of a ‘low-cost, high quality’ outcome. I don’t disagree with Dey and I hope Thapur is right, though I believe there remains a need to consider how and under what conditions the public holds itself accountable considering the significant role it plays in providing the demand for businesses in the first place.

[1] N.Dey works for the MKSS(Mazdoor Kishan Shakti Sangthan), Suchna Evum Rozgar Adhikar Abhiyan and NCPRI(National Campaign for People’s Right to Information). G.Thapur is the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of The Avantha Group.