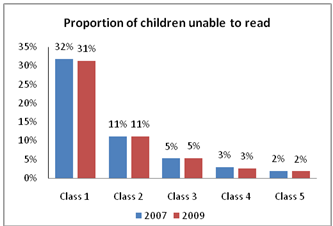

For quite some time now, India’s education system and policy has been in a state of torpor and seems to be waiting for little short of a miracle to shake itself out of the rut it’s in. While it is clear that the education sector has historically suffered from underfunding, this is only part of the story. What is as important as the resources we pour into the machine is what we are able to extract from it. And here, as a quick comparison of reading levels for primary school students across India shows, we have an almost perfect status quo across three years (see Figure 1). The number of children unable to solve a simple arithmetic problem (not shown here) also shows a very similar pattern. This is all the more disturbing since absolute allocation to education has increased in the recent past, though it is still significantly short of the normative target of 6% of GDP. Clearly, we need to look beyond the monetary aspect and take a closer look at service delivery, or the quality of teaching if we are serious about making a tangible difference in education outcomes, especially if we take into account that a large part of the education budget is dedicated to teacher salaries.

Source: www.asercentre.org

The problem of making teachers more accountable in order to raise the quality of teaching is not a problem endemic to India. Recognising the falling standards of the public education system in the US, President Obama and the Dept. of Education launched the Race to the Top programme in 2009, whereby states wanting access to programme funds must, amongst achieving other targets “improve teacher and principal effectiveness based on performance”. This has spawned extensive debate on assessment of teacher efficacy and how to best incentivise teachers. Teacher compensation in the US is a function of individual qualifications and experience and is generally negotiated by unions. Hence, the concomitant lack of performance based pay has led to claims that the current policy pushes high performers out of the profession and pulls in low performers. Performance incentives for teachers thus have two main objectives: to reward better performance with better pay and to retain better performers in the teaching profession. The most common way of assessing teachers is through examining student performance, the premise being that students of effective teachers would show greater improvement in test scores. While this seems like a sensible hypothesis, we should not take it at face value. Studies from across the globe have shown mixed results, though most of them corroborate our proposition. The difference in these results most likely emerges from the form of incentive given to teachers, study design as well as local conditions.

A 2009 paper by Muralidharan and Sundaraman looks at this problem in a very detailed manner. It describe the results of a randomised evaluation of a teacher incentive programme conducted in government-run primary schools (for two academic years 2005-06 and 2006-07) in rural Andhra Pradesh. 500 schools were chosen randomly and split into 5 groups of equal size.

| Group | Incentive

Category |

Description |

| A | Individual | Teachers to receive bonus based on performance of their students |

| B | Group | Teachers to receive bonus based on performance of all students in the school |

| C | Supplies | Schools received cash grants for supplies |

| D | Teacher | Schools received cash grants for an extra teacher |

| E | None | Control group |

The average cash bonus for teachers was approximately 3% of a typical teacher’s salary. Students were evaluated at the beginning and end of the academic year and surprise visits were made during the year to assess teacher and student attendance and teaching methods. At the end of the evaluation period, researchers saw that students in Group A and B schools did better than those in control group schools for all classes in consideration. Individual school characteristics (size and infrastructure) or student demographics apart from household income levels did not seem to have a bearing on the results. Interestingly, children’s grades in science and social science also improved despite the fact that only mathematics and language teachers had been offered bonuses, indicating the presence of positive spillovers. There was also some evidence of change in teacher behaviour – while attendance rates did not alter significantly, interviews revealed that school teachers in Group A and B were more likely to have set class and home assignments, taken extra classes and paid more attention to weaker students. Teacher incentives also turned out to be more cost effective than cash grants to schools: while incentives and cash grants both cost an average of Rs.10,000 a year, students in teacher incentive schools “showed test score gains that were three times larger than students in schools that received a grant or an extra teacher.” Finally, while Group A and B school performance had been evenly matched in the first year of the study, individual incentives worked better than group incentives in the second year of the study.

This study thus sends a strong message that individual incentives work; however, implementing a merit pay system is not as easy. Firstly, the context specific nature of a randomised evaluation study means that it is not easy to generalise these results. More importantly, before thinking about adopting this on a broader basis, we need to have standardised notions about how much improvement should entitle a teacher to make the grade, literally. Also, if we accept the fact that tests are not the best indicator of student ability, how can the same test score in turn be a gauge of the teacher’s performance? The biggest problem now is that if teachers themselves are not in favour of such a policy (if the mass protests by unions in the US are any indicator), they will have an incentive to subvert the “top-down push” for evaluation.

With the implementation of the Right to Education, making teachers accountable has never been more essential for India. The push for an evaluation system for teachers definitely has great appeal to academics and policymakers and has shown positive impacts on learning levels in studies; however it is unlikely to create much of an impact unless we can create a comprehensive and smooth rollout strategy which has never really been India’s forte. It is perhaps time to get down to the drawing board.

Anirvan Chowdhury is a Research Associate with the Accountability Initiative.

The

The  Mandakini Devasher

Mandakini Devasher In Bihar, the Paisa survey was held from 12th to 16 December in Purnea and Nalanda districts. In total, the survey covered 40 schools in the state. In the attached article, Dinesh Kumar a PAISA Associate with the Accountability Initiative in Bihar shares some of the experiences of the survey in Purnea. The article is in Hindi.

In Bihar, the Paisa survey was held from 12th to 16 December in Purnea and Nalanda districts. In total, the survey covered 40 schools in the state. In the attached article, Dinesh Kumar a PAISA Associate with the Accountability Initiative in Bihar shares some of the experiences of the survey in Purnea. The article is in Hindi.

Under AI’s flagship project,

Under AI’s flagship project,