How far has India progressed on securing welfare of all? This blog is part of a series which uses data to unpack the status of health, education and policy reforms in India’s 71st year of freedom. The first blog of the series can be found here.

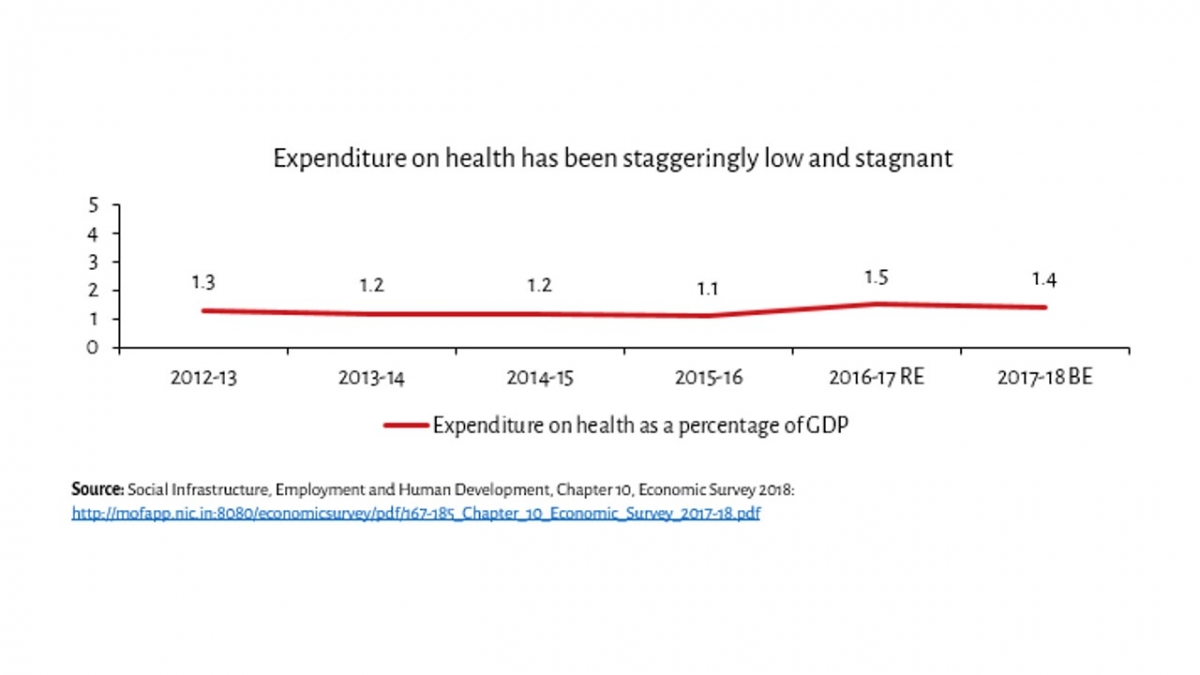

Poor health and nutritional deficiencies have become somewhat of a staple in the country. The loss of life due to ill-health are astronomical in both personal and social terms. These come along with significant economic losses to families, a large number of whom live on the margins of society. With such deprivation and the changing shape of India’s health crisis, one would expect the government in any developing country to ramp up healthcare funding. However, these expectations are dashed while looking at government spending (state and centre combined). The share of expenditure on health as a proportion of GDP has remained stagnant over the years.

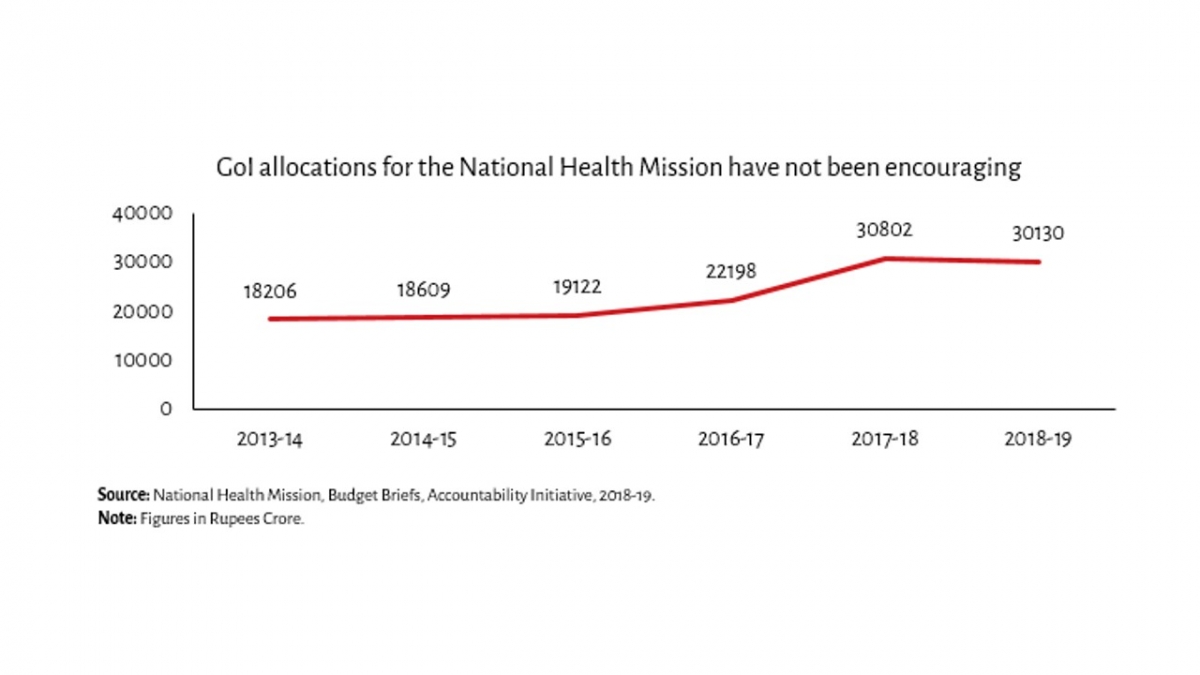

Funding for the National Health Mission (NHM), the Government of India’s largest health programme, too remained largely immobile from 2013-14 to 2016-17. While allocations jumped in 2017-18, they have decreased by 2 per cent in 2018-19, in a year when the health crisis that India faces has been in sharp focus from the government. This decline in allocations is puzzling, considering the government has launched schemes like Ayushman Bharat only recently. While spending more isn’t a panacea, a lack of spending appears to reflect the low priority of public health in the government’s agenda.

Even within the limited funds spent by the government, spending smartly would be a priority. However, there seems to be a disconnect between the disease burden in the country and the direction of funding. Curiously enough, just a trivial 4 per cent was allocated to non-communicable diseases out of the total budget in 2016-17, while 6 out of 10 deaths in India are now a consequence of non-communicable diseases. To make matters worse, only 33 per cent of that meagre amount was actually spent.

A paralysed system

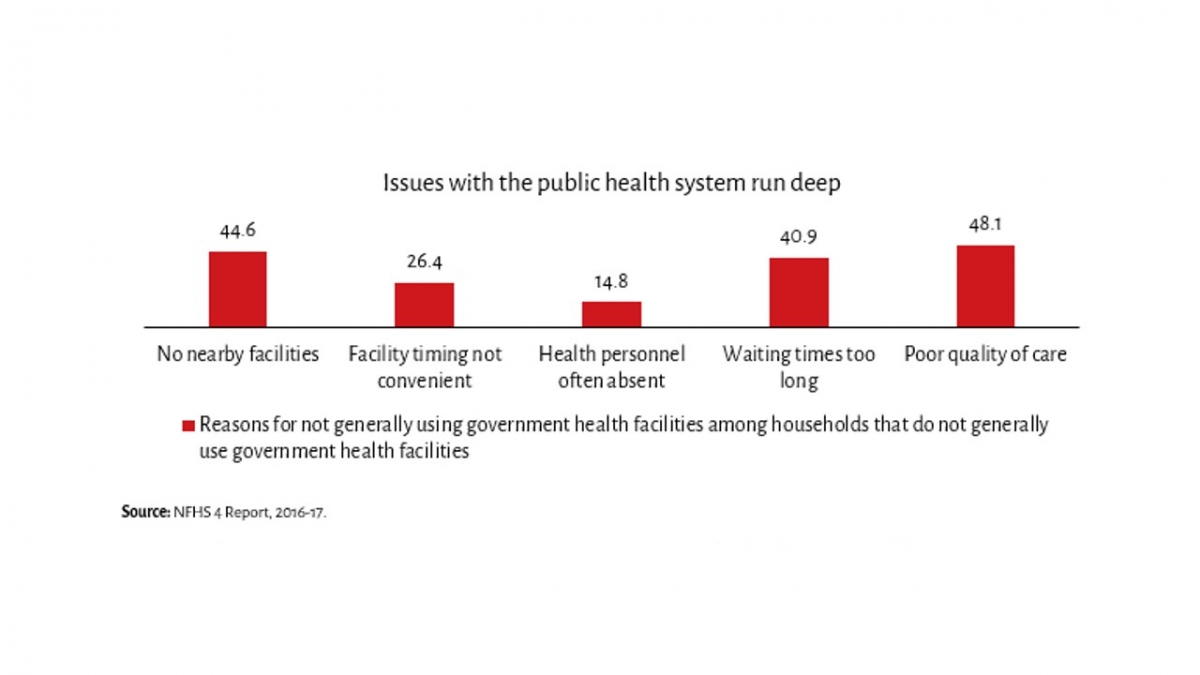

The Indian health system is paralysed in myriad ways and not yet adept in tackling the shifting disease burden. Given the increase in non-communicable diseases, specialists (surgeons, physicians, gynaecologists, and obstetricians) will be required with even greater urgency. There is however a shortfall in specialists, with 82 per cent out of required posts at Community Health Centres lying vacant.

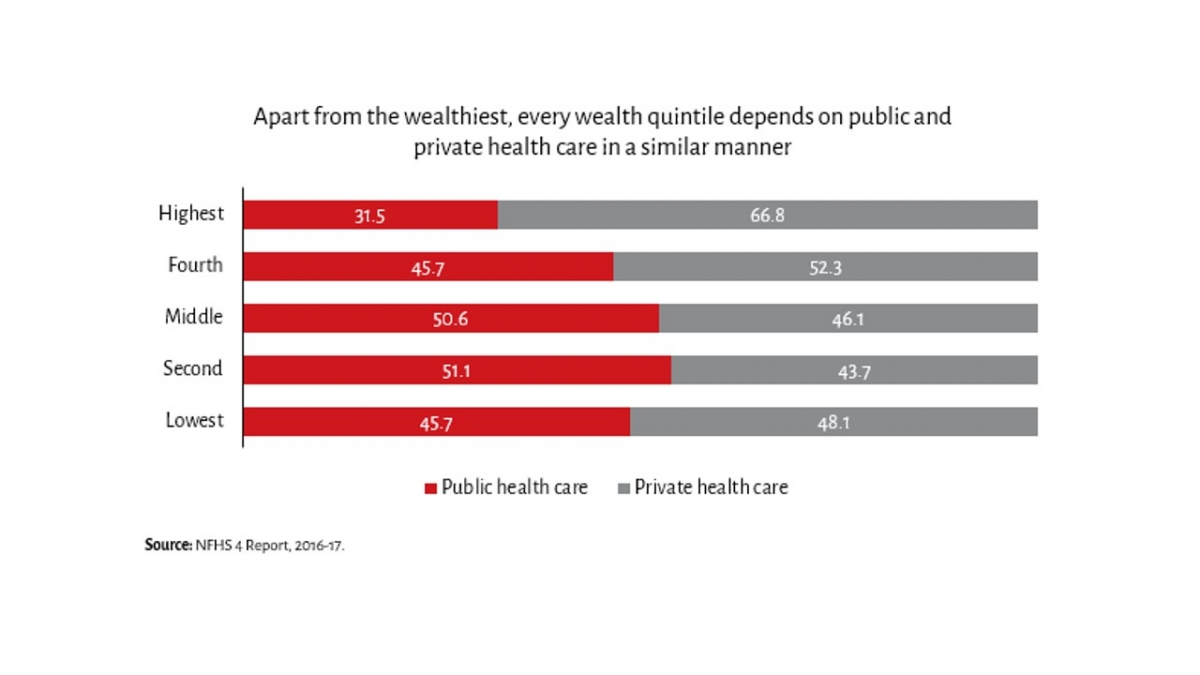

The ailing public health system has pushed several households, across the income spectrum to access private health care options according to various sources. NSS 2014 shows that there is a preference for private hospitals: In cases where hospitalisation was needed, 58 per cent used private hospitals in rural areas, while this number was 68 per cent in urban areas. NFHS 4 data shows a similar story.

One would expect the poorest to be more reliant on government services. However, the high percentage of people even amongst the poorest accessing private healthcare and the proliferation of spurious “doctors”, without formal medical training, who are sought for up to 75 per cent of primary care visits in rural India reflects the extent to which the public health system is paralysed. This has far-reaching implications in terms of poverty and inequality.

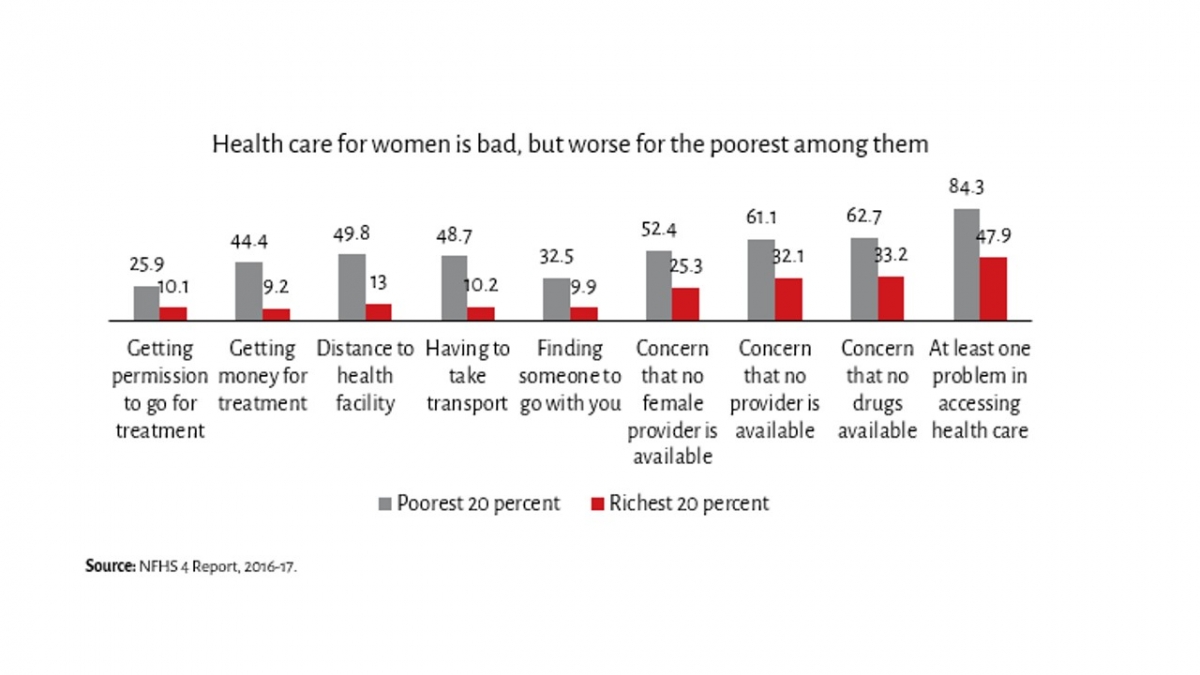

Amongst the poorest 20 per cent women, a staggering 84 per cent had at least one problem in accessing healthcare. Every single issue caused by the health system affects the poor far more than the rich. At the same time, a substantial 48 per cent women of the richest 20 percent faced at least one issue in accessing health care. The magnitude of the health care crisis that India faces is multifaceted – issues such as gender and caste discrimination and the way they play out cannot be ignored.

The maintenance of poverty

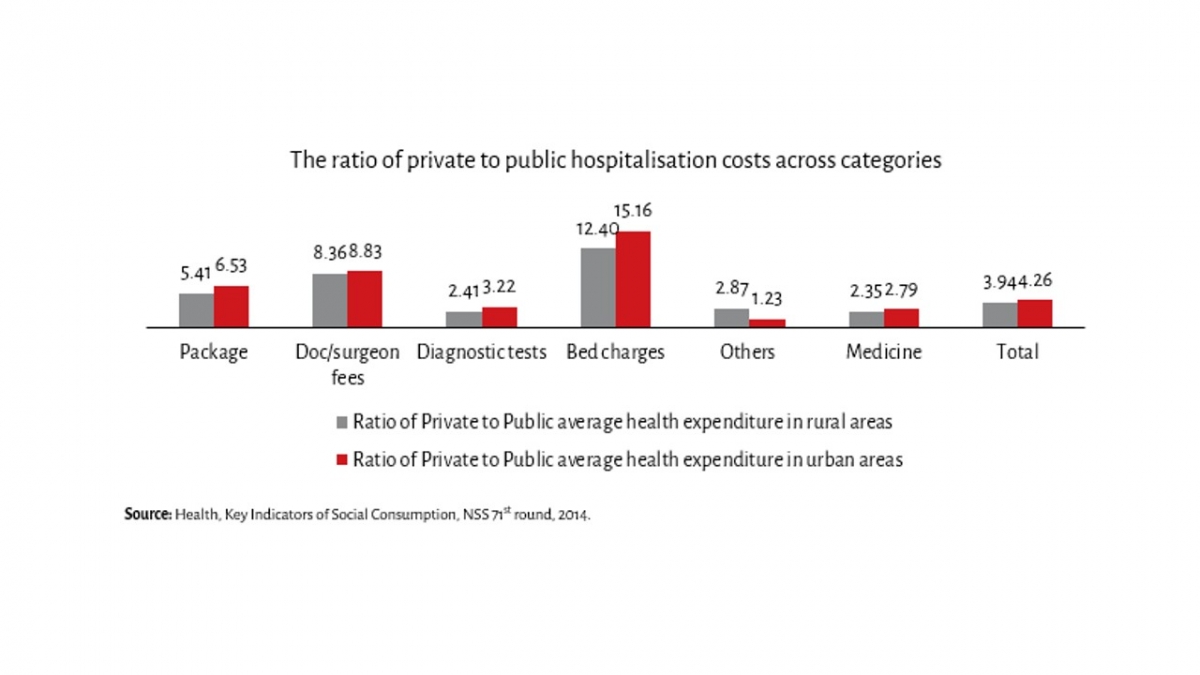

Due to obvious necessities, families end up spending far more than they would, had our public health care system been effective. The average hospitalisation cost in a private hospital is almost 4 times that of a public hospital in rural areas, and a little more than 4 times for urban areas. In particular, private hospitals charge far more for beds, doctors and surgeons, and medicines. In fact, bed charges in private hospitals are more than 12 times bed charges in government hospitals. Even private doctors are costlier than public hospitals – the average total medical expenditure for treatment per person was ₹462 in public hospitals in rural areas, versus ₹581 for private doctors or clinics. The corresponding figures for urban areas are ₹394 in public hospitals, and ₹658 for private doctors or clinics.

A shift in the disease burden to non-communicable diseases like cardio-vascular illnesses and cancer compound the problem. Out of 100 deaths in India, 28 are caused by cardiovascular diseases, 11 by chronic respiratory diseases, and 8 by various cancers. Private hospitals are four times as costly for cardiovascular diseases and chronic respiratory diseases, and three times as costly for cancer, compared to government hospitals.

This makes private health care unaffordable for many. Those that feel that private options are better end up paying a very high price for healthcare, often resorting to borrowing. As per NSS 2014, 25 per cent rural health expenditure and 18 per cent of urban health expenditure is financed by borrowings (excluding money borrowed from friends and family). Insurance may go some ways in easing the cost burden on families, but only 29 per cent households in the country have at least one member insured. This leaves a large number of people in a precarious position, susceptible to destitution due to health risks not covered by the state or personal wealth.

Since these expenditures are usually unplanned, they are a source of great anxiety for many. Imagine a household whose income is improving and may be close to escaping the clutches of poverty, but is pushed back down the income ladder due to a sudden expense. While the rich can draw on their wealth to deal with the problem, the poor often find their hard earned wealth quickly dissipating\and inequality in society persists.

Crucially, the costs of healthcare have been pushed on to individuals and families, and this has only added to the instability and uncertainty in the lives of the poor and in a mind-bogglingly unequal country, leaving people in a precarious position.

Can the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) help? The jury is still out, but lessons from previous insurance schemes like the RSBY clearly suggest that public funding for the private sector may be an exercise in vain. The profit-seeking private sector charges a higher amount than the public sector, and the government will have to shell out the costs. Furthermore, predatory practices (over-charging or over-treating), inadequate monitoring capability, and low state capacity are just some of the hurdles that PMJAY is likely to encounter. Instead, the state must step up in a more direct way rather than leave things to the private sector, if we are serious about larger goals – poverty alleviation and achieving basic human dignity and equality.

Another session that sent the students into an excited frenzy was the session on the reading of the Budget documents, where we think we encouraged many students to begin their own quest to become successful ‘fiscal detectives’.

Another session that sent the students into an excited frenzy was the session on the reading of the Budget documents, where we think we encouraged many students to begin their own quest to become successful ‘fiscal detectives’.