This blog is part of a series on the rollout and progress of e-Governance in India.

Last week, the Government of Karnataka announced that it would make the Aadhar number compulsory through legislation. The government said that its draft law would be modelled after the ones enacted in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Haryana.

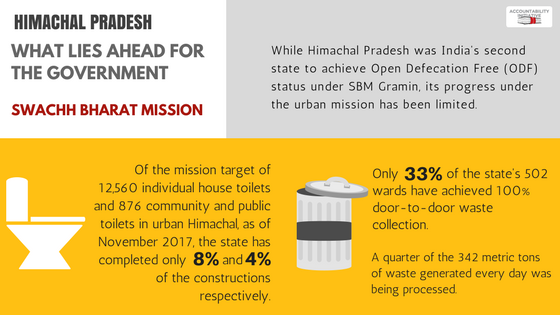

I have been walking the tightrope on Aadhar since the time it was introduced. I see on the one hand, the possibility of using a unique identity number for easing the process of obtaining a multitude of services from the government. Yet, I also see that the premature linking of Aadhar to various services by bureaucrats and politicians driven callous by their ambition, has led to many tragedies in the lives of the poor. Stories abound of distraught parents being unable to admit their children to school under the Right to Education Act, because they did not get their Aadhar numbers in time. There have also been instances of ration shops being unable to distribute rations because the lack of connectivity does not enable them to update the central database, which uses Aadhar, to record the rations given to individual card holders. We even watch mutely with horror at the recent report that a child, bereft of an Aadhar card, starved to death for lack of ration.

Looking beyond the current grim reality that faces many – particularly the poor – there is the not so remote possibility that an illiberal, malafide government that cares little for democratic freedoms, might use the Aadhar to conduct surveillance of a magnitude that cannot be imagined. This would be a horror scenario where dissidents may be electronically confined, with their bank accounts and credit cards frozen, their properties seized, their conversations tapped, their emails read and who knows their physical location tracked so that assassins can pick their time and place to pick them off.

Let us suspend for a moment, our scepticism and fear about a leviathan government running us into slavery through its ability to snoop over all of us, and look closely at what the Karnataka Government promises, in return for making Aadhar compulsory. The reports say that an Aadhar based platform created by the Central government, named the DigiLocker, will be adopted by the state. This will enable citizens to store all their critical documents in their own virtual locker in cyber space, thereby obviating the need for documents to be stored physically. Therefore, citizens will be able to keep virtual copies of their caste and income certificates, ration cards and other essential documents, in a secure space on the Cloud. The citizen, when applying for a government service that requires some of these essential documents, will be able to give access to the relevant government department to dip into the DigiLocker, extract the document required and issue whatever it is that they want. Thus, physical documents will not be necessary.

I have no doubt that all that is promised will become possible in the near future. However, the question is whether such innovations will make the government more responsive and accountable to the people. There, I have no reason to be optimistic.

Karnataka has had a long history of innovation in the digital sphere. The state established a Government Computer Centre in the early 1970s and has, since then, spearheaded several reforms in governance, using the possibilities of e-Governance. It filled one with pride to walk through the centre in those early days; with their whirring mainframe computers maintained in sterile, air conditioned environments. As a government officer serving in the state, in the mid-1980s itself, I had an opportunity to be trained in the government computer centre; an opportunity that was possibly not available to other service colleagues in other states. I remember how I was completely absorbed in the training, learning the possibilities of using Lotus 123 and MSDos, the pre-Microsoft offerings for spreadsheet and documentation. I remember the similar thrill that I felt when I opted for an early bird training in the centre in the mid-1990s, to familiarise myself with the first offerings of Windows. In terms of years, that was a mere two decades back; but it could be eons in the past, considering the strides that have been made since then in the capabilities of computers and software.

Yet, one thing remains constant; the Karnataka Government does not seem to have made any significant improvement in its responsiveness to people. True, certain things have dramatically changed, such as the accessibility and availability of land records, but in other ways, the state remains as non-transparent as it used to be.

This ought not to be construed as a criticism of Karnataka’s government, which is possibly much better off than that of other states. Yet, this dichotomy within the government, of a certain indifference and unresponsiveness that continues in spite of remarkable successes in streamlining certain self-contained processes, lingers. Indeed, Karnataka could be an excellent case study of this kind of widespread schizophrenia that affects other governments too.

Thus the question- wither e-Governance?

I will reflect more on this in my next few blogs.