पहले ब्लॉग में, हमने बिहार में प्रारम्भिक शिक्षा के परिवेश और कामकाज के संबंध में अपना विश्लेषण प्रस्तुत किया था। हमारे विश्लेषण के अनुसार, प्रशासन में मौजूद नियम-कानूनवादी संस्कृति और इसकी दो खासियतों – पदानुक्रम और नियमों व प्रक्रियाओं का कड़ाई से पालन – ने ऐसा परिवेश विकसित किया है, जहां स्थानीय अधिकारी स्वयं को स्कूलों में शिक्षण के मुस्तैद सलाहकार नहीं बल्कि महज नियमों का पालन करने वाले या “आदेश व सूचनाएँ पहुँचाने वाला डाकिया” मानते हैं।

इस भाग में, हम उपर्युक्त विश्लेषण के आधार पर शैक्षिक सुधारों की सफलता या विफलता के हालात को समझने की कोशिश करेंगे। हम मुख्यत: सुधार के उद्देश्यों और सुधार के लिए जिम्मेदार अधिकारियों के रोज़मर्रा के तौर-तरीकों के बीच के संबंध को समझेंगें। खासकर, हम यह जानना चाहेंगे कि सांगठनिक कार्य-संस्कृति और उसके कारण स्थानीय अधिकारियों की अवधारणा और तौर-तरीके किस प्रकार शिक्षा तंत्र के रोजमर्रा के कामकाज में सुधारों को शामिल करने की प्रक्रिया में मदद करते हैं या नुकसान पहुँचाते हैं। इसके लिए हमने बिहार सरकार की प्राथमिक शिक्षा नीति में बदलाव के संक्रामण काल के दौरान अध्ययन किया।

बिहार का ‘मिशन गुणवत्ता’

अप्रैल 2013 में, बिहार सरकार ने सरकारी प्राथमिक विद्यालयों में पढ़ रहे विद्यार्थियों के शिक्षण नतीजों को सुधारने के लिए एक नई नीति “मिशन गुणवत्ता” की घोषणा की। इस मिशन या कार्यक्रम के दो घटक थे। पहले घटक का उद्देश्य प्रशासन और स्कूल प्रक्रियाओं को मजबूत करना था। दूसरे घटक के तहत, बच्चों को उम्र के बजाय, ज्ञान के स्तर के आधार पर कक्षा 3 से 5 में पुन: समूहबद्ध कर स्कूल-समय में ही दो घंटे की सुधारात्मक शिक्षा दी जानी थी। इसके लिए स्पष्ट लक्ष्य भी निर्धारित किए गए।

इस कार्यक्रम का विद्यार्थियों से संबंधित घटक विशेष रूप से दिलचस्प था, क्योंकि इसकी बुनियाद में शिक्षा क्षेत्र के प्रमुख गैर-सरकारी संगठन ‘प्रथम’ की भागीदारी में बिहार के जहानाबाद और पूर्वी चंपारण जिलों में किया गया एक प्रयोग था। महत्वपूर्ण बात यह कि, इन प्रयोगों को स्कूलों की मदद हेतु क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयकों के माध्यम से स्थानीय प्रशासनिक क्षमता के निर्माण के लिए डिजाइन किया गया था[i]। प्राय: ‘सही स्तर की पढ़ाई’ (TaRI)[ii] के नाम से प्रसिद्ध इन प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं से शिक्षण-सुधार के लिए एक तंत्र की ज़रूरत पर राज्य-व्यापी बहस छिड़ी जिसकी परिणति मिशन गुणवत्ता की शुरुआत में हुई[iii]।

हालांकि इस कार्यक्रम की शुरुआत बड़ी उम्मीदों और आशाओं के साथ की गयी, लेकिन यह अधिक दिन तक नहीं चल पाया। वर्ष 2013 से वर्ष 2014 की गर्मियों तक यह छिटपुट तौर पर चलता रहा, लेकिन जब हम 2014 के अकादमिक सत्र की शुरुआत में स्कूलों में गए, तब तक मिशन गुणवत्ता का फोकस शिक्षण संबंधी घटक से हट चुका था।

प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं की सफलता और शिक्षण तंत्र के नियमित कार्यकरण में अध्यापन के वैकल्पिक तौर-तरीकों को शामिल करने में अंतत: मिली विफलता में भारत में कार्यक्रम-कार्यान्वयन और शैक्षिक सुधारों से जुड़े महत्वपूर्ण नीतिगत प्रश्नों के उत्तर ढूंढे जा सकते हैं। भारत में सेवाओं की आपूर्ति संबंधी सुधारों को सांस्थानिक स्वरूप कैसे दिया जा सकता है? नियमित सरकारी कामकाज में कब और किन परिस्थितियों में कोई बदलाव संभव हो पाता है? और वे कौन सी स्थितियाँ हैं जब बदलाव का विरोध होता है, उसका स्वरूप बदल दिया जाता है या उसे विकृत कर दिया जाता है?

सफलता की शर्तें: यथास्थितिवादी सरकारी तंत्र या डाकिया प्रवृत्ति में बदलाव कैसे हो सकता है?

जहानाबाद और पूर्वी चंपारण के प्रयोगों से उन स्थितियों पर प्रकाश पड़ता है जिनके होने पर सरकारी अधिकारियों की ‘डाकिया’ प्रवृत्ति में बदलाव आता है।

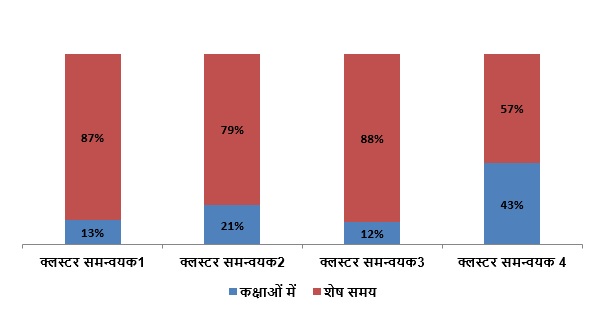

निश्चित ही, इस बदलाव में प्रतिबद्ध नेतृत्व की भूमिका महत्वपूर्ण थी जो लगातार स्थानीय अधिकारियों को प्रेरणा दे रहा था और प्रगति की नियमित निगरानी कर रहा था। लेकिन सफलता की कुंजी महज नेतृत्व की प्रतिबद्धता ही नहीं, बल्कि नेतृत्व के आयाम में बेहद बारीक बदलाव भी था। ज़िला अधिकारियों ने पदानुक्रम और आदेशों के पालन पर जोर देने के बजाय क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयकों के साथ सक्रिय संवाद और समस्या सुलझाने पर बल दिया। मसलन, जहानाबाद के जिलाधिकारी ने कार्यक्रम के कार्यान्वयन पर चर्चा के लिए समन्वयकों के साथ नियमित बैठकें कीं और उनसे प्राप्त जानकारी के आधार पर वरिष्ठ अधिकारियों से कार्रवाई करने को कहा। इससे क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयक सशक्त हुए।

“हमारी पहुँच सीधे जिलाधिकारी तक थी। हम मुद्दे उठाते थे समस्याएँ बताते थे…… फिर जिलाधिकारी अपने अधिकारियों (हमारे वरिष्ठ अधिकारियों) को कमर कसने और उस मुद्दे पर कार्रवाई करने को कहते। वे वरिष्ठ अधिकारियों से ज़्यादा हमारी बात सुन रहे थे”।

इन संवादों के साथ-साथ प्रथम द्वारा प्रशिक्षण भी दिया जा रहा था जिसमें मूल्यांकन, नई शिक्षा प्रणाली का व्यावहारिक अभ्यास और नियमित मदद शामिल थी। प्रशिक्षण पद्धति ऐसी थी कि क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयक शिक्षण की समस्याओं और उनके संभावित समाधान तक पहुँच पाएँ जिससे वे स्वयं को महत्वपूर्ण और सौंपी गयी ज़िम्मेदारी को निभाने के काबिल मानने लगे- हमारे द्वारा लिए गए साक्षात्कारों में यह तथ्य बार-बार दोहराया गया।

सारांश यह है कि प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं के दौरान जो नेतृत्व शैली और समस्याओं के समाधान का तरीका अपनाया गया, वह ब्लॉग के पहले भाग में वर्णित नियमित कामकाज के आम रवैये से बिलकुल उलट था और इससे क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयकों के नज़रिए में भी बदलाव संभव हुआ, वे खुद को महज “डाकिया” मानने की बजाय समस्याओं का समाधान करने वाले “परिवर्तन के वाहक” और “सशक्त अगुआ” मानने लगे।

लेकिन यह सफलता बहुत कम समय तक कायम रही। और इस विफलता के पीछे कार्यान्वयन के बेहद जटिल सवाल मौजूद हैं- सरकारी तंत्र में ऊर्जा और उत्साह का संचार करने वाले सुधार के प्रयास तंत्र के नियमित ढर्रे में शामिल करने पर टिक क्यों नहीं पाते?

बदलाव टिक क्यों नहीं पाता?

मिशन गुणवत्ता प्रयोग की अल्पायु और राज्य की शिक्षा प्रणाली में शामिल हो पाने में इसकी विफलता की प्रत्यक्ष वजह राजनीतिक परिवर्तन है। 2014 के राष्ट्रीय चुनावों के बाद राजनीतिक नेतृत्व और अधिकारियों के बदलने से सफलता की एक बेहद ज़रूरी शर्त यानि कार्यक्रम के लक्ष्यों और सर्वोच्च नेतृत्व में तालमेल को आघात पहुंचा।

निस्संदेह विफलता का यह एक कारण है, लेकिन कई ऐसे प्रश्न अब भी अनुत्तरित हैं जो यह समझने में मददगार साबित हो सकते हैं कि प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं और मिशन गुणवत्ता के प्रारम्भ में दिखा उत्साह राजनीतिक बदलाव और नेतृत्व परिवर्तन क्यों नहीं झेल पाया? जैसे, क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयकों ने शुरुआत में खुद को ‘सशक्त’ महसूस किया तो इससे उनके नज़रिये में स्थायी बदलाव क्यों नहीं आया और वे खुद को अकादमिक सलाहकार क्यों नहीं मानने लगे? जब शुरुआती जोश कम हो गया तो अध्यापकों ने उनसे सहयोग और भरोसेमंद सलाह क्यों नहीं मांगी? और अध्यापकों और क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयकों ने कार्यान्वयन के शुरुआती चरण में जो तौर-तरीके सीखे थे, उन्हें कक्षाओं की नियमित गतिविधियों में शामिल करने से भला किसने रोका था?

हमारे विश्लेषण से पता चलता है कि नियम-कानूनवादी कार्यसंस्कृति और इसके द्वारा पोषित “पदानुक्रम और आदेशपालन पर आधारित डाकिया” प्रवृत्ति से कक्षाओं में पढ़ाने के तौर-तरीकों में सुधार के प्रयासों में किस हद तक बाधा पहुंचाती है और विकृति आती है। व्यवहार में ऐसा कैसे होता है, इसका एक उदाहरण नीचे दिया गया है।

शिक्षण से कोई लेना-देना नहीं

जब हमने उत्तरदाताओं से स्कूल में बच्चों के सीख न पाने के कारण बताने को कहा, तो आश्चर्यजनक रूप से प्रशासन के हर स्तर पर जवाब एक-से थे। डाकिया प्रवृत्ति के अनुरूप ही हरेक ने शिक्षण संबंधी समस्याओं के लिए ऐसे कारकों को उत्तरदायी बताया जिन पर स्थानीय प्रशासन का कोई नियंत्रण नहीं होता। मसलन खराब नीति-निर्माण, कमजोर प्रशासन और सामाजिक-आर्थिक कारक जैसे माता-पिता की रुचि का अभाव शामिल हैं।

उत्तरदाताओं ने बातचीत में कभी भी शिक्षण नतीजों को प्रभावित करने में कक्षाओं में पढ़ाई यानी शिक्षण के तौर-तरीके, पाठ्यक्रम, पाठ्य पुस्तकों की गुणवत्ता, विद्यार्थियों के ज्ञान के स्तर की भूमिका का ज़िक्र नहीं किया। लेकिन जब प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं और बाद में मिशन गुणवत्ता TaRI से जुड़े अनुभवों के बारे में पूछा गया तो प्रशासनिक अधिकारियों और अध्यापकों, दोनों ने माना कि शिक्षण के तौर-तरीकों में बदलाव और कक्षाओं को पुनर्गठित करने से वास्तव में अध्यापक को प्रेरित किया जा सकता है और विद्यार्थियों की सीखने की गति में तेजी आ सकती है। कई क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयकों ने बताया कि पढ़ाई के नए तरीकों ने विद्यार्थियों में उत्साह भर दिया- मिशन गुणवत्ता के दौरान कक्षाओं में उपस्थिति काफी अधिक बढ़ गयी, विद्यार्थी अपनी समस्याएँ लेकर अध्यापकों के पास आने लगे। कई समन्वयकों ने टिप्पणी की कि पहली बार पूरा शिक्षा तंत्र ‘पढ़ने-पढ़ाने’ की बात कर रहा था।

इन फ़ायदों और शिक्षा में स्पष्ट बदलाव के अपने यथार्थ अनुभव के बावजूद, जब शिक्षा संबंधी समस्याओं के बारे में बात करने और उनके संभावित समाधान सुझाने को कहा गया, तो लगभग हर उत्तरदाता (एक को छोडकर) शिक्षण में सुधार सुनिश्चित करने के लिए, फिर से व्यवस्था से जुड़े ‘व्यापक’ मुद्दों के समाधान की ज़रूरत की बात करने लगा। प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं के संबंध में स्पष्ट उत्साह दिखा रहे उत्तरदाताओं सहित अधिकांश उत्तरदाताओं के मुताबिक, “पढ़ने-पढ़ाने” की यह पहल उपयोगी अल्पावधिक प्रयास था लेकिन शिक्षा प्रणाली की व्यापक व्यवस्थागत समस्याओं के समाधान में इसकी भूमिका नगण्य ही है।

हमारे विश्लेषण के अनुसार, समस्या की पहचान और समाधान के अनुभव के बीच कोई संबंध न जोड़ पाने की प्राथमिक वजह है सरकारी तंत्र का महज आदेशपालक होना। अधिकतर स्थानीय अधिकारी स्वयं को प्रशासनिक तंत्र का एक पुर्जा मानते हैं, और इसीलिए वे अपने काम में आने वाली चुनौतियों को अपने नियंत्रण से बाहर मानते हैं। इससे शिक्षण समस्याओं को समझने और उनसे सीधे निपटने के प्रति उपेक्षा की संस्कृति और जवाबदेही की कमी को वैधता मिल जाती है।

नतीजतन, कोई भी सुधार तब तक ही जारी रहता है, जब तक उसे आगे बढ़ाने के लिए कोई ‘अगुआ’ या ‘निगरानीकर्ता’ मौजूद हो। वास्तव में, हमारे सभी साक्षात्कारों के दौरान दोनों जिलों में सब ने यही कहा कि प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं के दौरान निगरानी बढ़ गयी थी और इससे स्थानीय अधिकारी अनुशासित और कार्य के लिए तत्पर रहते थे। हालांकि इस ‘अनुशासन’ से निश्चित ही यह सुनिश्चित किया गया कि तंत्र काम करे, लेकिन इससे कार्य-संस्कृति में कोई स्थायी बदलाव नहीं आ पाया। इसकी वजह यह थी कि इस दौरान क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयक और अध्यापक खुद से पहल करने के बजाय शीर्ष अधिकारी की अपेक्षाओं को पूरा करने का प्रयास कर रहे थे। इसलिए जब निगरानी कम हो गयी तो सरकारी तंत्र फिर से अपने रोज़मर्रा के ढर्रे पर चलने लगा।

“मिशन गुणवत्ता के दौरान कोई वरिष्ठ अधिकारी स्कूल नहीं आया… इसलिए हमने भी वैसे नहीं पढ़ाया जैसा हमसे अपेक्षित था”।

इस बात पर ध्यान दिया जाना चाहिए कि प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं से जुड़े कई पक्ष, बड़े पैमाने पर यह प्रयोग करने से हिचकिचा रहे थे, जबकि उनमें से ज़्यादातर ने इस तरीके की प्रभावकारिता की प्रशंसा की थी। इसे एक सफल प्रयास के विस्तार का अवसर मानने की बजाय क्लस्टर रिसोर्स सेंटर समन्वयकों ने इसकी प्रगति में बाधक संभावनाओं को गिनाना शुरू कर दिया। जैसा कि पूर्वी चंपारण के एक समन्वयक ने कहा:

“(प्रायोगिक परियोजना) सफल थी…….. लेकिन अब उससे बेहतर करने का विचार……इसके लिए अध्यापकों को प्रेरित करने और काम का सही माहौल विकसित करने के लिए और अधिक प्रयास करने होंगे”।

सही कार्य-संस्कृति और प्रबंधन परिपाटियाँ सफलता की कुंजी हैं

भारत में सामाजिक नीति में सुधार संबंधी चर्चाओं में स्थानीय अधिकारियों के दृष्टिकोण को खारिज करने और उन्हें उदासीन और शिकायत करने वाली नौकरशाही मानने की प्रवृत्ति रही है, ऐसी नौकरशाही जो अपनी उदासीनता और निष्क्रियता को सही ठहरने में लगी रहती है। हमारे शोध से पता चलता है कि परिवर्तन लाने के लिए स्थानीय नौकरशाही के दृष्टिकोण को भी विमर्श में गहराई से शामिल करने और ऐसा सांगठनिक ढांचा तथा कार्य-संस्कृति विकसित करने की जरूरत है जिससे उनकी शिकायतें दूर की जा सकें।

खासकर लैटिन अमरीकी देशों की नौकरशाही की सांगठनिक कार्य-संस्कृति और प्रबंधन परिपाटियों पर हुए हाल के अध्ययनों (Pires 2010, Piore 2010) से प्राप्त उपयोगी जानकारी के मुताबिक प्रबंधन के तौर-तरीकों में बदलाव के द्वारा – अधिक विवेकाधिकार देने और सहकर्मियों तथा वरिष्ठ अधिकारियों के बीच निरंतर संवाद के लिए मंच उपलब्ध कराकर फीडबैक को मजबूत बनाने से – नौकरशाही की प्रवृत्तियों में टिकाऊ बदलाव लाये जा सकते हैं। लेकिन, इसे हासिल करने के लिए भारत में प्रशासन संबंधी समस्याओं की समझ में भी बड़े बदलाव की ज़रूरत है-अभी यह समझ, संभ्रांत भारतीय प्रशासनिक सेवा (IAS) के अधिकारियों को पेश आने वाली दिक्कतों से ही जुड़ी हैं । IAS अधिकारियों को भरोसा ही नहीं होता कि ऊपर से कड़े अनुशासन के बिना भी स्थानीय अधिकारियों द्वारा बदलाव की प्रक्रिया आगे बढ़ाई जा सकती है। इस अविश्वास के कारण डाकिया प्रवृत्ति को और बढ़ावा मिलता है तथा सलाह और समस्या-समाधान पर आधारित नेतृत्व के स्थान पर पदानुक्रम आधारित नेतृत्व विकसित होता है। आज भारत में सेवाओं की आपूर्ति में सुधार के सम्मुख असली चुनौती यही है कि प्रशासनिक सुधारों की बहस का फोकस कैसे भारतीय प्रशासनिक सेवा के स्थान पर कार्य-संस्कृति के सवाल और प्रबंधन के ऐसे तौर-तरीके विकसित करने पर हो जिनसे संवाद संभव और सुगम हो सके।

Read English version here.

टिप्पणियाँ

[i] कार्यक्रम की परिकल्पना के मुताबिक, खासकर क्लस्टर समन्वयकों को, स्कूल आधारित कार्यकलापों के कार्यान्वयन में महत्वपूर्ण भूमिका निभानी थी।

[ii] J-PAI द्वारा TaRL पद्धति का कड़ा मूल्यांकन किया गया है। इस मूल्यांकन के ब्यौरे के लिए देखें www.povertyactionlab.org

[iii] हमारे शोध का उद्देश्य प्रायोगिक परियोजनाओं और सांस्थानिक बदलाव के संबंध को समझना था, हमने कार्यक्रम के दूसरे घटक यानि कक्षाओं संबंधी घटक का ही अध्ययन किया।

और जानकारी के लिए देखें

- Piore, Michael J (2011), “Beyond Markets: Sociology, Street-level Bureaucracy, and the Management of the Public Sector”, Regulation & Governance, 5(1), 145–164. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2010.01098.x

- Pires, Roberto RC (2011), “Beyond the Fear of Discretion: Flexibility, Performance, and Accountability in the Management of Regulatory Bureaucracies”, Regulation & Governance, 5(1), 43-69.

यह ब्लॉग मूल रूप से Ideas for India में प्रकाशित हुआ था।