If government offices could exist virtually, they would be remarkably similar to government websites, waiting/loading time included. Most information is available but not easily accessible, like a cabinet full of files stacked somewhere.

Moreover, accessibility to government data does not ensure accuracy; in fact too much information can also lead to a misrepresentation of facts. This blog post seeks to highlight the various obstacles faced while researching Government of India (GOI) schemes purely using government data available online. For an insightful account of missing records in government offices, have a look at this AI post (Link).

According to the Open Data Foundation (Link), a data user should ideally be able to:

- Discover the existence of data.

- Access data for research and analysis.

- Find detailed information describing data and its production process.

- Effectively communicate with the agencies involved.

- Share knowledge with other users.

Ideally. In reality however, there are many impediments to cogent data analysis.

The Indian government has taken several steps towards providing accessible information online. Extensive official guidelines explain what GOI websites should look like[1](Link), some pointers even address problems we’ve encountered. There’s also an analytics page(Link) rating these websites on the basis of their user interface and accessibility (the Indian Navy website is ranked highest). However, whether GOI departments take heed to these suggestionsis debatable.

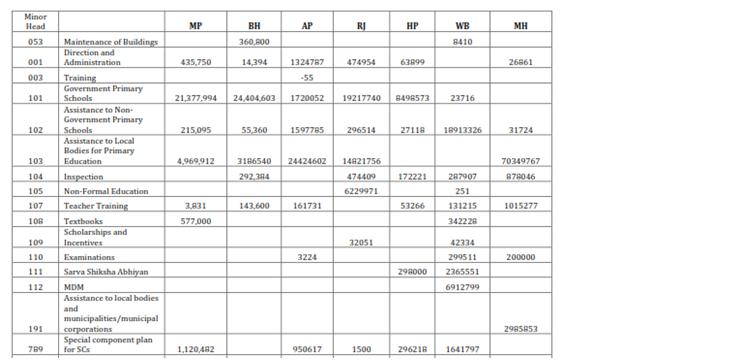

We can spot various issues in data while analysing schemes such as the Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan (NBA/TSC), Jannani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) and the Indira Awaas Yojana (IAY). Discrepancies are evident in their documents for Centre and State financial spending, physical achievements, State guidelines, Annual Action plans, Panchayat reports and question lists in the Houses of Parliament. This by no means covers the gamut of government data available online, it is simply a selection based on schemes we are currently interested in. Let us look at some of the problems faced while analysing government data.

Information Mismanagement: Data on government websites is not well organised.Basic documents such as ‘State guidelines for the implementation of the JSY’ are extremely hard to locate. It is unclear whether information exists at the Central or State level, on the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s website, or a specific National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) page, or even whether specific guidelines exist at all. Documents are not dated properly and oftentimes the fate of Recommendations is left to our imagination. Most documents are not published in machine-readable formats such as Excel or Word that are conducive to further use. They are usually in a non-editable PDF format, where some say,“data goes to die” (Link). After much metaphorical running around, one is still unsure about the information they have accumulated, largely due to data not being presented in a consistent and sequential manner.

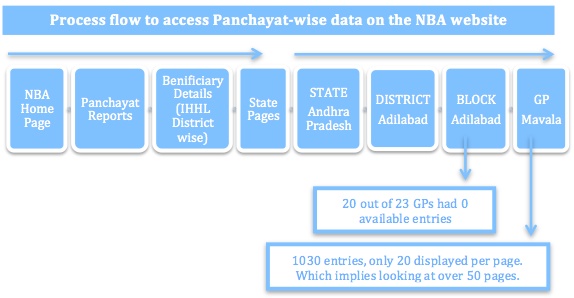

Sometimes these websites provide so many permutations and combinations for viewing data that extracting the required information becomes quite challenging. Certain data heavy pages promise information that is still about 8 clicks away, which only leads to another new set of pages to examine. For example, while checking entries for toilets constructed since 2001, we looked at Panchayat-wise data on the NBA website (Link):

This ten-minute process is for one GP, in one Block, in one District, in one State. Even if we analyse GP entries for just one State, it takes over a week to collate.

One can argue that this is precisely why datasheets have been compiled on these websites: to gather and present data in one place, but when inconsistencies such as double counting appear, we have no choice but to check the numbers ourselves. We undertook this more in-depth analysis precisely because in another GP; Anukunta (Link) 2 cases of identical BPL card numbers existed. This is also an example of data discrepancy, because the identical numbers exist only in the downloaded Excel version of the GP data and were different numbers on the NBA website.

Lack of standardisation of units and terms: Units of measurement especially for financial reports are not standardised across documents. It requires limited skill but a considerable amount of time to convert the lakhs to crores and vice-versa. However, a more tedious process is figuring out what the exact time period of a year is for different government ministries.

For example,figures for funds “released during the year” (2011-2012) according to NBA (Central government) data (Link)in 9 states is exactly double the figure given in the individual State Annual Action plans (2012-2013).Further fact checkingrevealed that theseAction plans did not include the grant received in March because the plans are prepared for April-January. While this explains difference innumbers, it also illustrates that a very substantial grant amount remains unaccounted for in the State plans. Excluding such vital information can mean incomplete research analysis and conclusions.

Data Discrepancies: Another shortcoming in data stems from data inconsistencies within and across different government sites.For example NBA numbers for physical achievement on one page might not match another NBA datasheet, technically providing the same information. Perhaps different calculation methods were employed, but usually no explanation is provided.This leads to uncertainty regarding which data is correct, since achievement is measured inconsistently. Another discrepancy is related to BPL/Antyodayacard numbers. Sometimes they’re an amalgam of 15 alphabetic and numeric characters (Link), sometimes the name of the beneficiary is identical to their card number (Link)and sometimes the numbers area sequence starting from 01 (Link).

Lastly, while an impressive amount of information is available on the websites of the Houses of Parliament, their Questions Search still needs refining. For example, searching for the ‘Indira Awaas Yojana’ does not bring up any hits for irregularities in the scheme, unless the term ‘irregularities’ is specifically mentioned. Additionally, IAY and ‘Indira Awaas Yojana’ bring up separate results, and when the terms are combined, the search bears no results whatsoever. Ideally, it should pull up any question with the term IAY in it; otherwise this can result in the omission of critical questions. Nonetheless, the inclusion of a ‘Wit and Humour’ page (Link) gets a nod of approval.

Data needs to be organised, synchronised and standardised in such a way that it is simpler, cleaner and faster, and serves its primary purpose of providing accessible and correct information. Promoting accountability requires access to information. Even though the Indian government has taken some measures towards providing better access to data, an overall upgrade and clean up of GOI websites is urgently required.

[1]For an example of an effective, user-friendly interface take a look at the UK governments website (Link).

Ask anyone where the Anganwadi Centre (AWC) is in Paschimi Gaon (name changed for privacy) in Lucknow and you are directed to an Anganwadi worker’s house. Its courtyard has a large mat where 15 children aged 3-6 years are sitting, playing with broken toys. The walls are covered with posters of alphabets so faded that they look more than a decade old, and the nearby hand-pump no longer works. This is Mamta Didi’s house, an Anganwadi Worker (AWW) for the past 19 years.

Ask anyone where the Anganwadi Centre (AWC) is in Paschimi Gaon (name changed for privacy) in Lucknow and you are directed to an Anganwadi worker’s house. Its courtyard has a large mat where 15 children aged 3-6 years are sitting, playing with broken toys. The walls are covered with posters of alphabets so faded that they look more than a decade old, and the nearby hand-pump no longer works. This is Mamta Didi’s house, an Anganwadi Worker (AWW) for the past 19 years.