The much awaited results of the 2012 National Achievement Survey (NAS) of Class III and Class VIII students are finally publicly available.[1] The third round of the survey, conducted as part of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) is deemed to be one of the government’s most comprehensive educational assessments. The survey collects information about the achievement levels of students in reading, mathematics, science and social science across a sample of government and government-aided elementary schools.

How do the NAS results differ from those of the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) [2]? The answer is – they aren’t comparable – so let’s not even get into that debate. The methodology and the objective of each study is different. While ASER is meant to be a dipstick analysis of basic competencies in reading and mathematics across rural India, conducted by community volunteers, in the child’s home; the NAS is a school-based, grade specific, country-wide assessment (covering both rural and urban) but limited to government and government aided schools. In fact, NAS was envisioned to officially monitor learning achievements under SSA in mathematics, science, language and social science. Not surprisingly, the results of the two surveys are not comparable. (For details on the different methodologies see here[3])

To give the reader an overview of the NAS methodology – The Class VIII survey was conducted between March-May 2012 for summer closing schools and November-December 2012 for winter closing schools. The survey used tests and questionnaires to gather information from 188,647 students in 6,722 schools across 33 states and union territories (UTs). In addition, questionnaires were used to collect information on schools, teachers, and pupils’ school experiences and home backgrounds. There is a three stage sampling process. First, districts were selected based on the number of Class VIII students enrolled. Second, the requisite number of schools was selected. In most states, the sample size was around 250-300 schools. Finally, around 5000 Class VIII students were selected at random for each subject and tested.

This time, NAS has used Item Response Theory (IRT) [4] as the basis for analysing test results, as well as, reporting on outcomes. The IRT is an international standard for assessment surveys that; a) uses mathematical models to assume a statistical connection between the difficulty level of the test item, the ability of the student, and the probability of that student being successful at a particular item , and b) allows for results to be compared between groups and over time. To elaborate – scores are placed on a scale from 0-500, which is normalised with a median of 250. This was later updated based on the results. The results can thus be used to make comparisons between states as well as across time. To give an example – if State A’s score in science increases from 260 to 270 between 2012 and 2015 whilst State B’s decreases from 270 to 250 during the same time, direct comparisons can be made even if the scores have been derived from different students, taking different tests at different times as the reporting scales are fixed.

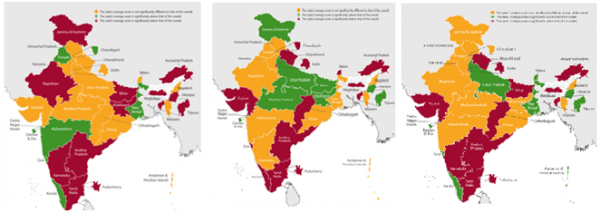

| Class VIII Achievement Results: Reading Mathematics Science |

Legend:

Yellow: The states score is not significantly different to the overall score

Green: States average score is significantly above the overall

Red: States average score is significantly below the overall.

Below are some of the main findings from the NAS.

- First and foremost, despite different methodologies – the NAS confirms the findings of ASER and other studies as it also identifies learning as a big challenge facing Indian education.

- Unsurprisingly, there is significant variation both across states and subjects but also diversity in achievement between the highest and lowest performing students within the states. (See map above) It is important to highlight, that for reading comprehension the national average was 247, for mathematics (245) and 251 for science out of a possible 500.

- Similarly, there are differences in terms of equity. Students who come from Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes or Other Backward Classes tend to perform worse than students from the General category.

- The study also dispels the science and maths gender myth as it finds – nationally, there is no significant difference between boys and girls in achievement levels in maths, science and social science. In fact, girls outperformed boys in reading comprehension. Some of the main exceptions to this were Kerala (where girls outperformed boys in the first three subjects); West Bengal (girls performed worse than boys in these subjects) and Bihar (where girls performed worse than boys in reading)

- There are differences in rural vs. urban: In science and mathematics, rural students out-performed urban students, in social science they fared equally. Only in reading comprehension do urban students do better than rural students

- Private tuitions also seem to be on the rise. In West Bengal, as high as 77% of students were taking private tuitions. (See Table 1)

Table 1

| States | Proportion taking private tuitions (NAS 2012) |

| Chhattisgarh | 8 |

| Rajasthan | 14 |

| Punjab | 16 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 20 |

| Tamil Nadu | 22 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 22 |

| Haryana | 23 |

| Maharashtra | 29 |

| Gujarat | 32 |

| Kerala | 36 |

| Jharkhand | 49 |

| Odisha | 56 |

| West Bengal | 77 |

| India Average | 35 |

NAS also seeks to understand the factors that impact learning. As mentioned earlier, the survey asked questions regarding household background and other school related factors and governance issues. Key findings are highlighted below:

Household related factors

- Students with only one sibling outperform by a small but statistically significant amount those that who have two or more brothers.

- Medium of instruction makes a difference

- Higher the parents education, greater the probability of the student doing well.

School related factors

- Co-educational schools do better than single sex schools.

- Schools with pucca buildings tend to do better.

- Government aided schools have lower performance, even when the key factors such as socio-economic status of parents, location etc. are taken into account.

- Of the different entitlements, scholarships seem to have the highest impact.

Teachers and Teaching Related factors

- Students who had their homework checked by their teacher every day tend to do better.

- Students that reported group work with other students in solving mathematical problems perform significantly better in maths.

School leadership and governance seems to play a key role in achievement

- Students of schools where head masters also teach, tend to do better.

- Learning achievement of the schools which are inspected more is better and finally,

- Having VEC/AEC/SMC committees is associated with better performance.

Going Forward

So what does this mean in terms of going forward? Let’s start with the positives. As the report itself says, “NAS is an education health check that helps to establish the spread of what students know and can do at specific stages of education cycle“[5]. Further, by assessing students in Class VIII and given that RTE norms ascertain that no child shall be held back in elementary school, it throws some light into the level of preparedness of students entering secondary schools. Further, the questionnaires on factors affecting learning can help teachers as well as policy-makers identify areas of concern and rectify them.

Going forward, I think it will be important move beyond debates of which method (ASER vs. NAS) is a better method of measuring learning outcomes. Instead, we should recognise that each assessment increases our understanding of the status as well as the context in which students learn. In fact, when several complementary studies[6] point to the same direction, it only makes the case stronger. This fact is recognised even by the 12th Five Year plan, which focussed on the need to focus now also on learning outcomes.[7]

There are however a few things that NAS needs to consider going forward. First, is a question of timing. One of the biggest advantages of ASER is the quick turnaround rate between conduction of the survey and survey results. As a result, ASER is able to create a regular, timely [8] update of the status of affairs in elementary education, thus giving evidence upon which policy changes could potentially be made. The survey conducted in 2012, is finally available on the website in 2014. Even after this 2 year lag, only the state report cards are publicly available. The complete data is yet to be made publicly accessible.

Second, is a question of data quality. Call me a sceptic, but I was slightly surprised with the results of Uttar Pradesh outperforming most other states including some of the south indian states in maths, science and social science. In fact, according to Class V results report by NAS, the “NCERT team reflected that there was no monitoring done from their end while the survey was being conducted and they relied too heavily on the state and district coordinators to carry out the monitoring tasks” [9].

Having a strong monitoring mechanism and robust data checks could alleviate some of the concerns regarding data quality. Details of this information should further be made publicly available. In fact, even DISE despite its large coverage has a 5 percent data rechecking in place.[10]

Third, recent years have seen a mushrooming of private schools across India and increasing enrolment in these private schools [11]. Often these schools remain out of the radar to the point that we do not even have an idea about their numbers let alone the quality of education in them. While the NAS currently only looks at government and government aided schools, going forward, it is important and necessary to also find a way of assessing private schools.

Finally, let’s make the data more user-friendly so that researchers like us and even policy makers can use it easily!

(p.s. – a word of advice for those who want to access the reports – use Internet Explorer as it doesn’t work properly on Chrome)

[1] The NAS had previously released the Class V survey conducted between 2010-11 in 2012. The latest NAS was officially released in February 2014, however data was not publicly available.

[2] More details on ASER are available at: http://www.asercentre.org/

[3] The document describes the differences between ASER and the NAS report for Class V, Cycle 3, 2010-2011 released in 2012.

[5] NCERT (2012), NAS Class VII Summary Report. Available online: http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/11%20March%20National%20Summary%20Report%20NAS%20Class%20VIII.pdf

[6] ASER, Educational Initiatives etc

[7] http://planningcommission.gov.in/plans/planrel/12thplan/pdf/12fyp_vol3.pdf

[8] ASER reports are released in January which is when the SSA’s planning cycle is underway.

[9] http://www.ssatcfund.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=TEJBnXMcOiQ%3D&tabid=2508

[10] Despite this, DISE themselves have been struggling with making DISE data even more rigorous.

[11] DISE State Report Cards, ASER (2012), ASER (2013)