In all the debates about rights, social sector schemes and pushing towards ensuring quality services to citizens, there is but mere passing mention about the importance of performance management and administrative reforms over and above the implementation failure of public services[1]. This blog looks at the growing emphasis on the features of the social sector schemes, and overlooking the other side of the (administrative) coin which looks at the management style and employer-employee relations in a public sector context. This has been discussed by Lant Pritchett[2] in the context of ‘State Capability Trap’ in reference to governance & public sector reform.

This view is definitely not new, and some efforts have been made towards inching closer to more output-based large scale performance management tools. While there are presently vertical lines of appraisal systems in place across departments and ministries, and supervisory checks are present on paper for those implementing schemes at a local level (see blogs on the process in the education sector by my colleagues), as well as citizen-led monitoring through social audits for large schemes like the MGNREGA, there are serious gaps when it comes to understanding performance at a macro level. From the World Development Report 1997, “The State in a Changing World”[3] we see a growing interest in the significant role that formal and informal institutions played, and the need for an overarching Public Sector Reform agenda that focused on ‘managerial capacities, developing positive organisational cultures, and providing incentives for performance both at individual and organisational level’. India added this to their agenda with the UPA government setting up the 2nd Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) in 2005, which brought out 15 key recommendation reports over a period of 5 years. This was followed by the Public Services Bill in 2007 which reviewed and set up a Management System for Public Service.

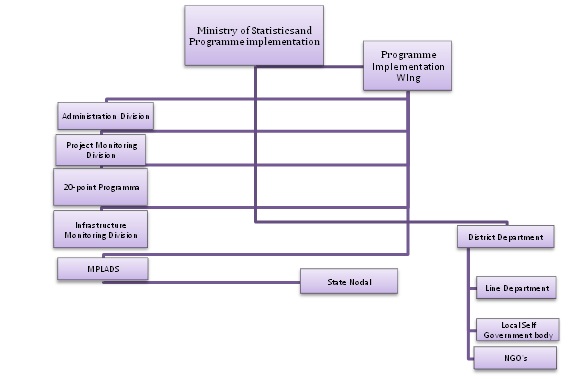

A colleague at AI a few years ago had written a blog about the introduction of the PMES or the ‘Performance Monitoring and Evaluation System’ in 2009 (see here). Since then, quite a few evaluation reports have been published . So what is the PMES? According to the Administrative Reforms Commissions 10th Report in 2011, “Performance management is the systematic process by which the organization involves its employees, as individuals and members of a group, in improving organizational effectiveness in the accomplishment of organizational mission and goals”[4]. A subset of performance measurement, which looks at the inputs, goals, impact and effectiveness defined by the departments themselves of a particular service/scheme, performance management looks at the planning, reviewing and evaluating the performance of individuals and departments, looking towards developing capacity (skill building) and promoting innovation for a result-oriented work process. A visual of what this looks like is given below

(Source: Adapted from Second Administrative Reforms Commission’s Tenth Report, 2008)

This is preceded by the processes that Ministries and Departments engage in, when structuring projects. According to the Guidelines for the Results Based Document (RFD), each Department (with consultations with their officers) sends in the RFD to the Ministry by February end, specifying their goals and success indicators for the year. After being reviewed by an Ad- Hoc Task Force (ATF) (which consists of domain experts, former Secretaries to the Government of India and retired Corporate Heads) this document, and the Budget, is approved/edited by March every year by the Cabinet Secretariat. This is followed by a review of the document by the High Power Committee- HPC (which consists of the Cabinet Secretary, Finance Secretary and other senior officials)- and submission of the report to the Prime Minister. The Departments/Ministries have to send in the year-end evaluation by May of the following year- with reviews again by the ATF and the HPC.

The strength of forming such a system is the recognition that there is a need for assessing performance of individuals in a system, done so in relation to the targets prepared at the beginning and in sync with goals of the department and not limited to the individual’s capacity. This type of review existed previously only for IAS officers (by the Department of Personnel & Training), but was not done for state level officials until recently. Taking a few pointers from the Appraisal format that currently exists by the Ministry of Personnel, the PMES allows for a concrete and systematic assessment of officials and their work in a standardized way and makes each Department review (and hopefully revise) their own specific structure of appraisals. A performance system, then, aims to removes any vague criteria of ‘good or bad’ for promotion, and moves towards improving motivation and creating an incentive based rating system that places the individual in a larger context of the organisation. This is backed by creating avenues for developing interests and aligning potential of an officer to what they will be doing in the future.

While these all are a welcome change, there are, as with every new system, challenges they need to overcome. At a broader level, most reforms that take an administrative avatar, have quite frankly, failed to take off, or be implemented. Even the recommendations that were offered by the ARC have only been taken up by a handful of States (though almost all of them were accepted by the Cabinet committee)- and it is unclear whether this was done with intentions for actual implementation or as a box-checking task. Problems such as pre-decided budgetary allocation, inflexible program structure or even the lack of a conducive work environment can hamper a government official’s performance.

This, in addition to blurred reporting structures (as is seen in most projects that have an inter-department characteristic or being handled by multiple agencies) can create hurdles for those who are finally held accountable for inaction. The website, where a few reports are available, does not showcase any documents on action taken if an official has fared poorly in the performance rating, or what incentive-schemes were developed, or the type of innovations that may have led to promotions. Putting this out in the public domain could be the start of increasing transparency in this area.

Recent debates emphasise the challenges that are seen with outputs (or lack thereof) of particular schemes, plagued with officials that do not implement well, usurp public resources and are inefficient. What has not gained much traction in these debates is the point of internal public sector reforms that has tried to go hand in hand with more schemes and more public services offered. If we look at the sheer number of schemes that exist in this country, and the number of officials on the ground and the incentives that currently exist, we can assess the gargantuan task that lies ahead. While steps have been taken to bring attention to this, the lack of enthusiasm in terms of the uptake of previous recommendations is telling of the future course of action.

[1] Performance of social sector schemes, 2014. http://finmin.nic.in/WorkingPaper/Performance_MSSSchemes.pdf

[2] ‘Capability Trap: The Mechanisms of Persistant Implementation Failure’ http://www.cgdev.org/publication/capability-traps-mechanisms-persistent-implementation-failure-working-paper-234

[3] World Bank. World Development Report 1997. http://wdronline.worldbank.org/worldbank/a/c.html/world_development_report_1997/abstract/WB.0-1952-1114-6.abstract

[4] Government of India. Department of Administrative Reforms & Public Grievances. ‘Performance Management in Government’ http://indiagovernance.gov.in/files/performance-management.pdf