An executive order passed by a federal secretary supersedes the collective will of the country`s parliamentarians. Shocking as this may sound, the observation is based on evidence. Invisible bureaucrats that lurk behind politicians decide how our resources are to be put to use.Politicians complain about the unbridled power wielded by bureaucrats but have done little effectively to reduce these powers. Consider, for example, the following tale that unfolded when I submitted a request for information in the context of the Special Publicity Fund, under which the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting spends over Rs20m every year.

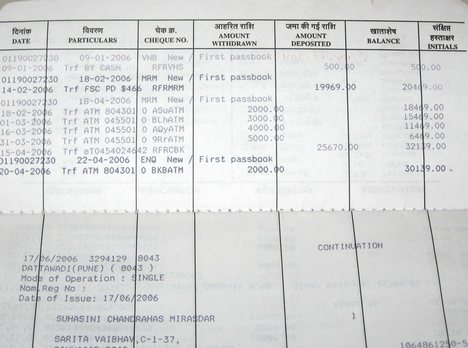

I asked for certified copies of the strategy and advertisement plans to spend under the Special Publicity Fund from Oct 1, 2002 to March 20, 2008, in addition to certified information about the names and addresses of the media houses, public relations firms, consultants or journalists that received funds under this head during this period. Further, I requested certified copies of the contracts under which the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting had released funds from the Special Publicity Fund to such recipients during the same period.

The ministry did not provide the information within the 21 days stipulated by the Freedom of Information Ordinance 2002. Consequently, a complaint about the ministry`s failure was lodged with the federal ombudsman`s office and on Sept 29, 2008, it directed the ministry to submit a report.Nearly a month later, on Oct 24, 2008, the ministry replied that the Special Publicity Fund is similar to the secret fund provided to any government organisation, as are allocations made under the head of `A03914 — Secret Services Expenditure`.

Furthermore, the ministry maintained, the Special Publicity Fund is “strictly utilised in accordance with the rules and regulations governing the Secret Services Expenditure issued by the Financial Division from time to time”. An analysis of the budget books revealed that the Special Publicity Fund was included in the `Others` category in the 2008-09 budget. Other allocations in this category were to the Pakistan Institute of National Affairs, Internews, the Institute of Regional Studies and News Network International.

When this issue was raised with the ministry, it responded that the fund had been declared `secret` by the Finance Division through a letter dated April 29, 1976. Yet when access to it was sought, the ministry said that the letter was not available with it. The federal ombudsman determined that the allocation for Secret Service Expenditure had the ID 1358 while the Special Publicity Fund had the ID 1357. Furthermore, it determined that on the New Item Statement for the Special Publicity Fund the entry against ID1357 had been titled `Secret Service Expenditure`. Here the plot started to really thicken.

Through the federal ombudsman`s office, we demanded that details pertaining to the utilisation of the Special Publicity Fund be provided to us. But the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting did not provide the letter under which this budget head had been declared secret expenditure. It maintained that the information could not be provided since it was secret expenditure, and had been declared thus through an executive order of the federal secretary of the ministry, under powers vested in him by the Cabinet Division.

Yet the fact is that parliamentarians approved the Special Publicity Fund as a normal budget item, just as they did other budgetary allocations for the Pakistan Institute of National Affairs, Internews etc which were also placed in the `Others` category of the 2008-09 budget. The Special Publicity Fund was not passed as a secret service expenditure item.

Therefore, the federal secretary`s executive order that treated it as such is in conflict with the collective will of parliament.

In a parliamentary democracy it is the collective will of the people, as represented by parliament, and not a federal secretary`s executive order, that should have supremacy.

This entire exercise, with the Special Publicity Fund as a case study, raises three important questions: first, how many budget items are passed by parliament as normal items but treated as secret expenditure? Secondly, how can the political leadership exercise its authority in the way in which public funds are utilised? And third, how can the judicious utilisation of public funds be ensured?

The prerogative to declare any public fund secret expenditure should rest with parliament alone. Powers vested in this regard with federal secretaries should be revoked through an act of parliament. Furthermore, the relevant parliamentary committees should exercise their powers to oversee how the funds are being utilised. As things stand, a federal secretary submits a certificate to the accountant general of Pakistan containing one line about how many funds have been utilised.

We need to enact effective laws regarding the right to information to ensure the transparent functioning of public departments. Such laws have been adopted in over 90 countries.

It is about time the two major political parties made good on the promise they made in the Charter of Democracy about enacting an information law and repealing the ineffective Freedom of Information Ordinance 2002, the Balochistan Freedom of Information Act 2005, and the Sindh Freedom of Information Act 2006. The new information laws should provide easy access to information. The ombudsman`s office, which is toothless as an appellant body, should be replaced with an information commission as is the case in many countries round the world. Being the most populous province, Punjab needs to enact a right to information law that can serve as an example for the other provinces.

The writer works for the Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives and can be contacted at zahid@cpdi-pakistan.org

The article was published in Dawn on December 7, 2010.

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), the nodal agency for the implementation of the RTI Act has proposed a series of amendments to the RTI (Regulation of fee and cost) Rules 2005 and the Central Information Commission (Appeal Procedure) Rules, 2005. Specifically, the amendments seek to restrict the number of words that an applicant can use while filing an information request under the RTI Act 2005.In addition, to curbing the word limit, the new rules also seek to restrict the questions filed under the RTI to one subject matter. DoPT invited citizens and organisations to send in their comments on the draft rules by 27th December 2010. The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative has drafted preliminary comments on the amendments and submitted these to the government for consideration (see attached).

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), the nodal agency for the implementation of the RTI Act has proposed a series of amendments to the RTI (Regulation of fee and cost) Rules 2005 and the Central Information Commission (Appeal Procedure) Rules, 2005. Specifically, the amendments seek to restrict the number of words that an applicant can use while filing an information request under the RTI Act 2005.In addition, to curbing the word limit, the new rules also seek to restrict the questions filed under the RTI to one subject matter. DoPT invited citizens and organisations to send in their comments on the draft rules by 27th December 2010. The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative has drafted preliminary comments on the amendments and submitted these to the government for consideration (see attached).

Mandakini Devasher

Mandakini Devasher In Bihar, the Paisa survey was held from 12th to 16 December in Purnea and Nalanda districts. In total, the survey covered 40 schools in the state. In the attached article, Dinesh Kumar a PAISA Associate with the Accountability Initiative in Bihar shares some of the experiences of the survey in Purnea. The article is in Hindi.

In Bihar, the Paisa survey was held from 12th to 16 December in Purnea and Nalanda districts. In total, the survey covered 40 schools in the state. In the attached article, Dinesh Kumar a PAISA Associate with the Accountability Initiative in Bihar shares some of the experiences of the survey in Purnea. The article is in Hindi.

Under AI’s flagship project,

Under AI’s flagship project,

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), the nodal agency for the implementation of the RTI Act has proposed a series of

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), the nodal agency for the implementation of the RTI Act has proposed a series of