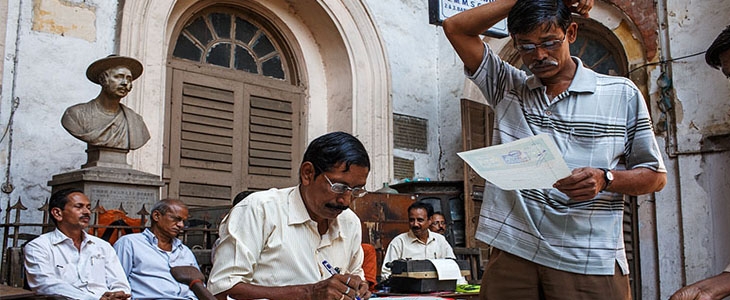

Recently, some colleagues and I at the Accountability Initiative conducted a day long workshop with a batch of development management students. The emphasis was on relaying the message that in order to become better development practitioners in the future they must use credible research findings to inform their decisions. After concluding the session, a student came to me with a set of questions which she was obviously feeling shy about posing.

She said she had understood the importance of looking at evidence to inform her practice, but had no idea where to begin looking for it! “Which journals should I look at? Where do I look for these journals? No one has ever taught me this,” said this young woman with a couple of years of experience of working closely with migrant labourers. I was struck by her comments. It made me think back to my own experiences of working with government officials, and reflect on how wide the gap is between development practitioners and researchers.

Today, calls for “evidence-based policy making,” “data driven policies” are increasingly getting louder in development circles. This is a positive sign. Policy making processes in the Government have been notoriously opaque. Often driven by political priorities of ruling parties, policies are shaped under imperfect conditions- administrators have very little time to formulate the policies; and they have to work with limited knowledge about the scale of the issues. As a result, policies and programmes tend to leave a lot of questions unanswered for both frontline implementers and the public which is ultimately at the receiving end. So, more demands for sound policies backed by evidence are and should be welcomed by all.

That brings us to the next stage – supplying the evidence. This is where some big set of questions and challenges lie for everyone involved in policy making and implementation. Who is producing the evidence? How is it being produced? How is this evidence being treated and absorbed in the policy cycle?

Hunt for reliable evidence

We find ourselves in a predicament. On the one hand, there’s plenty of meaningful research going on in universities which can directly inform and enrich policy making and implementation. But this research is not always tailored to answer or solve particular policy related questions. This is because universities in general do not orient students to look at their projects in that light.

On the other hand, there’s a dearth of research, particularly on niche, sector specific issues, where policy planners could really use all the help. I will attribute this mainly to the fact that practitioners – people who are working in non-government and government organisations who plan and implement crucial programmes daily – simply don’t have the time to share their sectoral expertise. They cannot afford to spare a lot of time to weave in further research in their plan cycle, so important issues that merit further study don’t easily come to see the light of day.

Moreover, development practitioners – people who could really find it beneficial to dip into the pool of knowledge universities are sitting on – tend to scoff at trained researchers for being too theoretical, impractical or idealistic. Seeped in jargon, academic studies are quite often by and for academic consumption. This need not always be the case.

That the Government has several research bodies producing high quality research, which is used by national and state level planners to make plans, is unchallenged. But the dearth of high quality non-government sources of evidence is not healthy. Like in the case of any monopoly, when there is a dearth of competition, users don’t have an option but to go by what is on offer.

Absorption and application of evidence in the policy cycle

When practitioners are inclined to look for evidence, a simple Google search may not be very helpful to begin with since it may throw up hundreds of unverifiable results. In my experience, practitioners, more often than usual, don’t have the bandwidth to sift through all the research, and assess its quality.

So even while there is talk of incorporating evidence into the policy cycle, one must ask what is being done to build the capacity of planners to leverage what is already available. Where to begin looking for the evidence; how to assess credibility of the data; how to do basic interpretation of data and its application – these are areas that all development practitioners should get basic training on to help them discharge their duties better.

Need to bridge the gap between evidence builders and users

The onus of addressing these gaps lies with both practitioners and researchers. Both evidence builders and evidence users must reach out and create platforms to further the dialogue. The question then becomes – what can such platforms and formats for engagement look like? We need to urgently start asking and addressing these questions if we don’t want “evidence-based policy making” to remain empty rhetoric.