The School Management Committee (SMC), is a legal provision[1] for a partnership between community and school. The point is to implement a shared vision for a ‘good education’ for the neighbourhood’s children. It is based on the belief that even people with little personal experience of schooling, have a vision for their children’s futures and can make considered decisions about their educational goals. It follows that they can therefore also contribute to the plans of the local school to implement these goals in the school years. Given this, it requires both parties to collaborate in a participatory partnership to see this process through from start to finish.

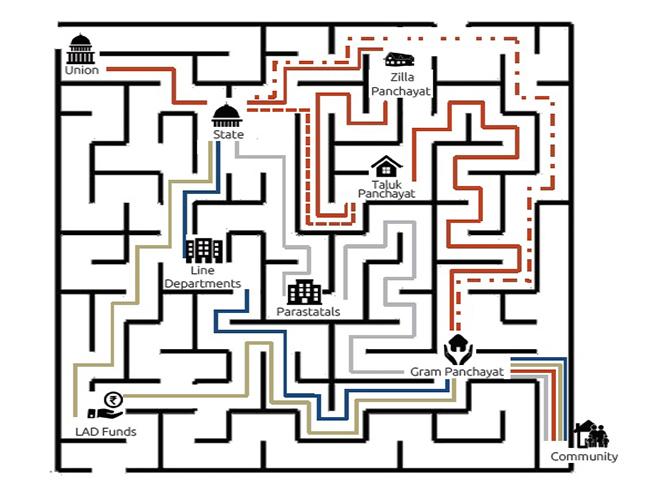

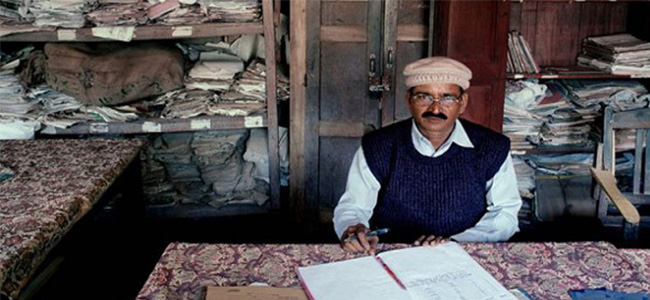

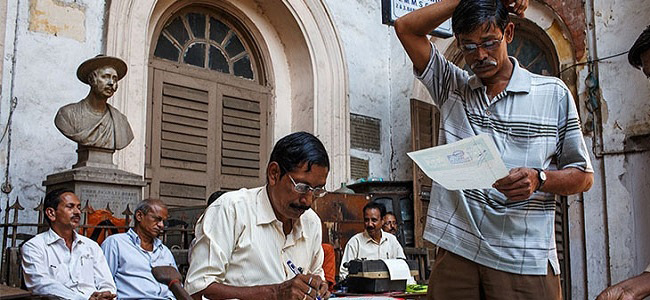

In fact a community’s preparation to participate is as complex a journey, as is building the will and competencies of the bureaucracy to allow for it. While an idealistic policy and equally hopeful law is in place, they are not buttressed with institutional capacity to build the required skills, leave alone attitudes to render effective implementation. Even knowledge, the relatively uncomplicated component of competency, is not communicated in full. Over the years, Accountability Initiative’s (AI) contributions have aimed at easing access to the latter. Good minds are at work across the nation, assisting solutions to the challenges cited above. Everyone agrees that reform is a slow undertaking. What is not slow however, is the retort which has become a refrain, that the real and hidden cause of sluggish progress is a lack of personal integrity amongst stakeholders. AI has been building an argument against this contention in its work understanding governance. Considering this, our focus has been on frontline bureaucracy.

AIs team documents and analyses the everyday professional realities of the experiences of this layer, and analyses the complexities of the variables involved so as to provide implementing agencies (both government and non-government) with a clear and substantiated canvas on which to draw strategy for reform.

But, reality can be confusing. But, reality can be confusing. Truth is a point of view. As decisive and compelling as AI would like its advice to be, the truth is a tangled web and therefore solutions are seldom quick-fixes.

The Motiala (name changed) government Primary School is a case study, where all the stakeholders involved, can tick off the checkboxes on all the compliances on all manner of monitoring formats, but even then, the intent of the policy remains unserved. The school in Motiala is one of six that AI has been working with in Rajasthan for over a year[2].

The current Principal of the government Primary school in Motiala was appointed to her post in 2014, after serving approximately 17 years in the school[3]. Suitable to her station as a young lady from a respectable family, she occupied herself with continuing her education after school. Quite pointlessly, (and alarmingly) she completed a Bachelor’s in Education and a Master’s Degree in the same year (1992), then proceeded to complete yet another Master’s Degree three years later (1995). She then promptly applied for a PhD, which has remained unfinished as she busied herself applying for a government teacher’s job the year after (1996). She was selected to join a school in a Block of District Jaipur.

Whatever wisdom supported the formulae that the Rajasthan government used to deliberate this posting, the need or demand for service notwithstanding, the distance of the school from their home not being kosher; the appointment and hence the job was not approved by her family.

The process was repeated again in 1997, and once again she was selected for duty in the very needy Block. The difference was that the posting was in a village where her uncle was the Sarpanch. As requested by her family, the Sarpanch ‘approached’ the Block Education Officer (BEO) to facilitate a transfer.

The BEO of the block she was posted in earlier spoke to BEO of the block in which she wanted the posting; who, further pressured by her significantly established businessman brother, handed-over the decision of where she would be posted entirely to the family. She reports with pride that her father, mother and brother proceeded to tour the schools with available vacancies until they selected Motiala as it was at a convenient distance from their home and later, her marital home. The village has been her home away from home. She will tell you with pride that the villagers consider her a ‘gav ki beti’ (a daughter of the village). They keep a familiar watch over her that she finds comforting. The interactions are in terms of making them making sure she gets to and from school safely; and attends all social occasions celebrated by the significant families in the village. There has never been an SMC meeting in this school, save for one held on AI’s insistence[4]. The ‘beti’ being a regular visitor in homes of the most influential villagers, the Principal can’t imagine why there may be a need to hold a meeting. That the school may be excluding members of the community fails to occur to her.

There were a 110 children in the 2-room school when she joined as one of two teachers, the other being the acting Head Master. By 2009, when he was promoted, he taught her how to maintain all manner of administrative documentation, as the single pre-requisite to her becoming a Principal. This and the just-in-time problem-solving support she receives from the Nodal Officer is the only hand-holding that she has received to help her take on leadership of the school. She holds her lineage responsible for her losses too, as she blames being in the ‘General’ category to be the reason she has not been promoted yet. Her aspiration is to become a Second-Grade teacher, which will qualify her to teach classes 6-12 in a higher secondary school. In keeping with her lukewarm ambitions for her career and insignificant commitment to the mission of her job, she had plans to retire if the process of promotion takes too long or if the ensuing posting is inconvenient. After all her husband has a secure job in a leading public sector organisation and comfortable enough somehow to retire whenever he is ‘in the mood’. The recent demonetisation has required her to be ever so slightly concerned about holding a job, as it has hit her maternal home’s businesses in hundreds of lakhs; to the extent of making her father unwell.

The Motiala school has 30 children (21 girls and 9 boys)[5]. It is RTE compliant in terms of infrastructure and staff. DISE data lists 7 other government schools in an area spanning a 2.5 square kilometers. The closest is 500 meters away from this one, with 22 enrolments, and 2 teachers, was opened because of an initiative taken by a resident, then an officer in the education department. Because it was located in its own habitation[6] (‘dhaani’), and not the centre of the village and thereby not as accessible to all habitations, the villagers protested and asked for this school to be opened. The fact that there were also 10 private schools in the same Gram Panchayat, is some form of commentary on the quality provided by the government school. The fact that there is hardly any teaching at either school, with all children bundled into one classroom with a single teacher, concerns no one.

Conversations at the State about Motiala inspire no interest. For the scale at which the government operates, the financing of 7 schools with enrolments of 20-100 each, is an insignificant loss, despite DISE 2015-16 reports 33,298 Primary and 20,820 Upper Primary Single-Teacher Schools; which may have very similar stories. They are forgotten as no one can find any technical fault with the existing arrangement. Those who can, refuse to prioritise children’s learning over political or personal advantage.

[1] Clause 21 of the Right to Education Act (2009), which specifies that all schools (except unaided schools or those that do not receive any grants from Government or local authority to meet expenses)

[2] Accountability Initiative has been working in the Bassi block in Rajasthan, to ascertain the challenges to the education management as it takes on the task of running effective SMCs. Of the many levels of education bureaucracy we work with, there are 6 principals of schools who are provided inputs on coaching SMCs on fiscal literacy.

[3] Joined mid-year 1997. Appointed Principal end of year 2014

[4] Please watch a video of AI Paisa Associate Tajuddin Khan report on the successful SMC meeting

[5] Class 1: 4 girls and 4 boys, Class 2: 3 boys and 2 girls, Class 3: 1 boy and 5 girls, Class 4: 0 boys and 6 girls, and Class 5: 1 boy and 4 girls.

[6] A habitation has only 5-10 households

![[Hindi] Why is Accountability so Important in India? Watch this video to learn more.](https://accountabilityindia.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Animation20Hindi_27th20Jan_0.jpg)