Sustainability and Accountability Issues of Common Service Centres

24 August 2018

Wouldn’t it be great if each citizen in the remotest of parts of our country has easy access to all key government services? By easy access, I mean that citizens are able to use these services by visiting a nearby centre without the hassle of spending hours travelling to faraway government offices.

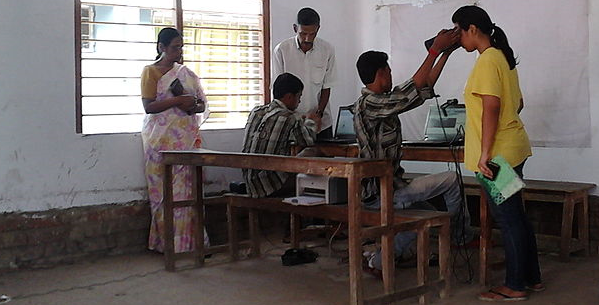

The central government has attempted to make this otherwise distant dream a reality by introducing the Common Service Centres (CSC) scheme under the Digital India Programme. Many states have set up such centres in the last three years with the purpose to provide IT-enabled services to citizens, especially in the rural and remote areas where accessibility has been a major challenge. The central government plans to establish at least one CSC in each of the 2.5 lakh Gram Panchayats across the country by the year 2019. These centres are supposed to function as access points for the delivery of essential public utility services, social welfare schemes as well as healthcare, financial, education and agriculture services. They will be run by local entrepreneurs. Services that a citizen can expect from such centres are Government to Citizen (G2C) services like online filing of passport applications, requests for PAN cards, Aadhaar cards, birth and death certificates, and the withdrawal of money from accounts much like in the case of banks. These centres also have the flexibility to offer Business to Citizen (B2C) services that include mobile recharge and bill payments, and the renewal of dish TV subscriptions.

At first glance, the setting up of CSCs looks like a revolutionary step towards providing last mile service delivery from a single access point in remote areas. However, multiple challenges in the manner in which this scheme is currently being implemented have become apparent. These challenges can be broadly grouped into two categories. First, concerns with respect to long term sustainability of these centres and second issues that highlight an accountability gap. I recently participated in a workshop organised by the Azim Premji Foundation where these issues were discussed and debated in detail based on the findings of a sample survey on CSC owners and citizens accessing CSC services across 10 districts in Jharkhand. Among the workshop’s participants were CSC owners, members of the government and Civil Society Organisations. The primary matter of concern that emerged in discussions was this – can CSCs operate as businesses maximising profits for owners while simultaneously playing the role of public services providers? Also, are enough checks in place so as to make them accountable to the people they serve and provide quality services?

Sustainability Issues

CSC owners are local village level entrepreneurs (VLEs) trying to make a livelihood out of the PPP model (private-public partnerships). While most of the G2C services are offered at rates decided by the government, some basic services like banking are offered for free. There appears to be an understanding in government circles that CSCs should provide a large number of services to expand their profits so as to remain viable. Herein lies a dichotomy. While these centres aim to be self-sustainable by way of profits, they are also expected to work as public service agents by facilitating citizens in accessing services in areas that are difficult for the government to reach.

Many village-level entrepreneurs in Jharkhand pointed out that the average profit earned by them in the current commission-based model is quite low (ranging from Rs 3,000 to Rs 6,000 per month). They cannot charge the citizens beyond the rates prescribed by the government for the services offered. At the time of writing this blog, although we do not have enough data on the average monthly incomes for CSCs in other states, representatives from Rajasthan who participated in the workshop also confirmed similar levels of profits with wide monthly variations. In the current design of the scheme, it is not possible to ensure a basic minimum income. Will the entrepreneurs sustain themselves on such low levels of income in the long run? A question mark is also raised on whether CSC owners can then put a limit to free services offered by their centres and focus more on paid G2C and B2C services. This ties in closely with a third and a fundamental issue- should citizens be charged at all for G2C services that are otherwise available for free in government offices and funded through the taxpayers’ money? For now, answers seem few.

Also, all the services offered by the CSCs are online digital services which require uninterrupted and speedy internet connection throughout the day. However, poor internet connectivity in many of the interior villages in Jharkhand hampers efficient service delivery to the citizens. This results in delay in service provision as well as poor quality of the same. Without a well-functioning digital network in place, these centres cannot perform their role as envisaged by government.

Accountability Gap

The PPP model of the CSCs presently lacks a strong grievance redressal mechanism in case of failure in providing a G2C service for any reason. For instance, if a certain service applied through a CSC is rejected or if benefits of a certain scheme do not reach a citizen, an entrepreneur running the CSC cannot be directly held accountable because he merely acts as a facilitator and not being part of the government, he does not have any decision making authority in the provisioning of the service. In such a scenario, a citizen finds it difficult to approach a government authority directly for grievance redressal since he was coordinating with the CSCs till that point. Even if a citizen chooses to lodge any complaint against a CSC, there is no clear-cut formal route of doing so that assures timely response. Of course, there are phone numbers or email ids mentioned online by government, but that does ensure necessary action within a certain specified timeframe. In such a scenario, the essence of efficient service delivery at the last mile is lost.

Jharkhand is a forerunner in establishing CSCs in the country. The survey findings revealed that there is an emerging misconception among citizens in the state that CSCs are substitutes for government offices. For instance, CSCs in Jharkhand offer Aadhaar registration as per the rate decided by government. Wherever such centres are functional and offering this service in remote localities, additional camps are not set up by the government. As a result, a user has no choice but to visit the CSC and in the process ends up paying from their pocket, which could be accessed for free in a government-run camp. Similarly, the survey revealed instances of CSCs being projected as substitutes for banks for basic banking services such as deposit and withdrawal of cash. In the absence of a strong accountability mechanism, such practices can lead to confusion and also breed corruption because a large number of CSCs do not have the facility of passbook updation, which for many rural citizens will be the only valid way of tracking funds in their accounts. Should a CSC be working as a substitute for a government office?

So, should I be as thrilled as I was the first time I learnt that CSCs have been set up in remote villages across the country and would function as a point source to access a range of government services? I still feel the setting up of CSCs is a great move but certain changes are needed to make them accountable, efficient and sustainable. A strong accountability mechanism ensures a formal route for grievance registration and redress, regular government supervision and monitoring of the centres for enforcement of mandates, transparency through mandatory display of rate-list for all services offered among other things are required. At the same time, changes such as developing a mechanism for the CSC owners to earn some basic assured monthly income, and urgent investment in rectification and development of broadband internet connection in rural areas will be important for the long-term sustainability of the CSCs so that they can successfully play their role as last mile public service providers.