Simplifying Spatial Planning

24 November 2018

This blog is part of a series on policy decisions, the causes and consquences of the Kerala floods. The first blog can be found here.

In my last blog I wrote about various new and innovative approaches to urban planning, which aimed to address the problems of traditional rigid approaches. However, we just cannot wish away the fact that implementation of plans will remain a problem as it is dependent upon broader socio-political factors outside the control of the planning system. It is not going to be easy to change the regulatory system and enforce decisions that are in the larger interest of society, because of entrenched legal rights and interests.

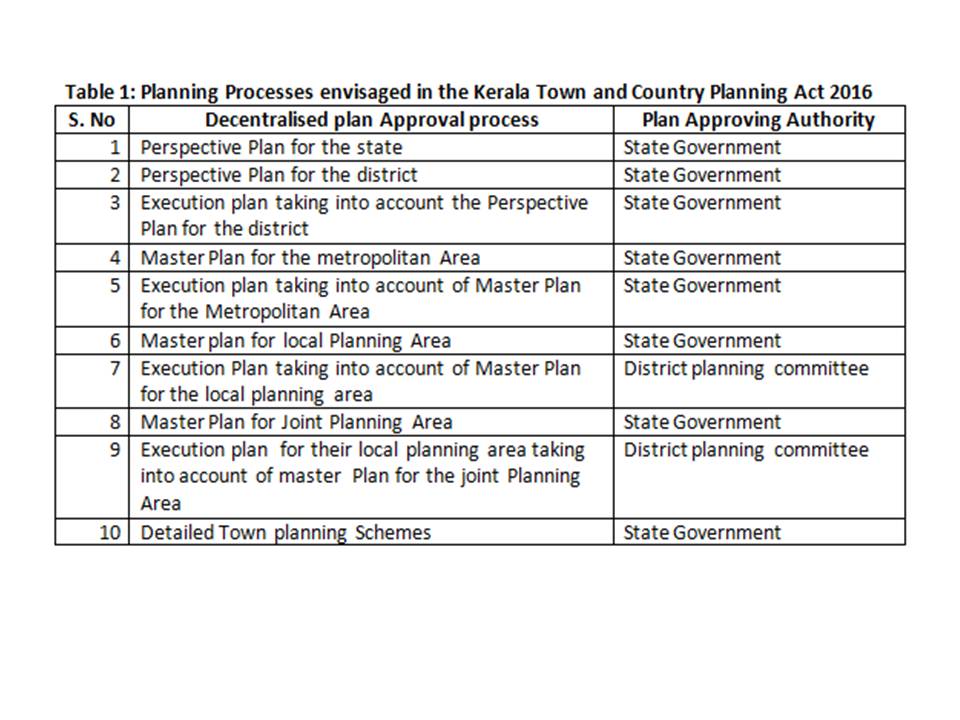

Having said that, a good place to start is to check out the different kinds of planning envisaged in the law. In the case of Kerala, as shown in the Working Group Report, there is a great deal of fragmentation when it comes to different planning exercises. The Kerala Town and Country Planning Act 2016 provides for the following kinds of plans to be prepared (Table 1):

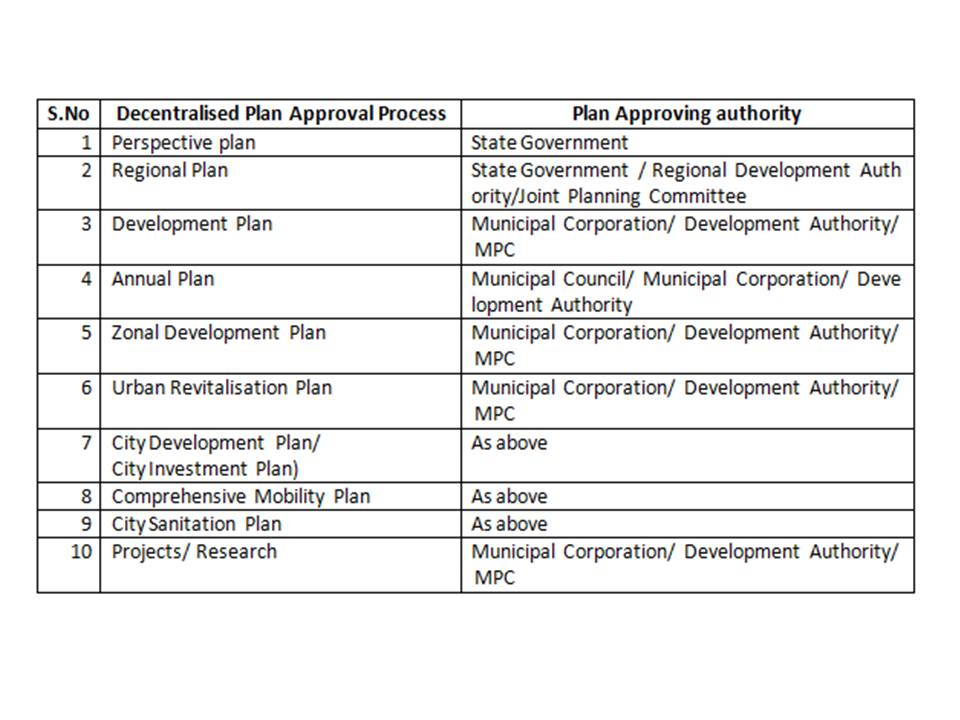

At the same time, there are other planning processes that straddle the spatial planning aspect and that are still in vogue, either as statutory processes, or as mandated by various funding programmes for urban development (Table 2):

The dichotomy between Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the wide variation between the approach taken by the Town and Country Planning Act 2016 and the adaptive approaches to urban planning envisaged through various schemes and guidelines. This creates plenty of scope for confusion and lack of coordination.

How does one overcome this recipe for planning disaster? The best way would be to reduce the number of planning exercises to the minimum required and then ensure that they interlink with each other in a manner that is easy to understand.

It is the state’s responsibility to approve the perspective plan covering the entire physical area of the state, including both rural and urban areas. At the same time, such an exercise cannot be undertaken without consultation with citizens. The best way to do this would be for the state government to declare a Charter of Urban reforms and Urban Governance Improvement Measures, in which planning is a key component.

There must be a regional plan, which conforms to the broad non-negotiable principles enunciated in the Charter of Urban reforms. The Regional Plan would guide individual master plans for each LG within the region. The emphasis in the Regional Plan would be on recognising the potential for economic growth of the UA concerned and strategising for reaching it.

Every city, town and /or Panchayat within the UA can prepare its detailed Master Plan within the broad framework of the Regional Plan. Whilst doing so, the Master Plan for each LG should not be developed as self-contained plans in isolation of each other. The Master Plan would then become the ‘comprehensive long term development policy’ for the LG, within the overall context of the urban agglomeration.

Then would come the next level of detail, which is the CDP for each local government, with a 5 to 10 year perspective.

Finally, the CDP is split into programmes; and implementable projects.

In my last and final blog on Kerala’s spatial planning, I will lay down the institutional mechanism that could support such an approach, as also what are the Hobson’s choices before the state, when planning for a safe and climate resilient Kerala.