Brokering Public Service Delivery in Delhi

27 May 2019

Informal mediation peopled by brokers, touts, middlemen has over the years embedded itself within public service delivery. Even as they are not within the government system, brokers have come to play an important role, and have reshaped it. The Municipality of Delhi is no exception. Who are these people, and how do broker practices impact governance?

I met Pankaj Sharma, 36, while researching a paper on informal institutions. For the past 15 years, he has been assisting people to complete their documentation for any work they may have at the zonal office of NDMC in Karol Bagh, a popular locality in the national capital. He is not employed by the government, and carries out his business sitting on a boulder or under a tree. He likes to be known as a Consultant, but came into this line of work by accident as a result of unemployment. A literate man, he started helping out an influx of people filing applications after a change in property tax norms in Delhi in the early 2000s.

“It was during that time that my friend asked me to come and help on these property tax applications for people i.e. filling the form, calculations and preparing paperwork, and we made a good Rs. 100 for every case,” he says. Pawan gradually gained familiarity with other government departments and operations, and became a viable bridge for citizens who came to the NDMC zonal office in Karol Bagh for any service.Sharma is part of a network of informal governance systems. The need for bureaucratic mediation such as his emerges due to monopolisation and weak accountability of institutions. Such weakness perpetuates the existence of ‘windows of opportunity’.

In simple words, brokers exist not just because of citizen demand, but also because of a system in which government service delivery cannot be easily held accountable by ordinary citizens.

Driven mainly by patronage networks, brokers, fixers or touts behave as ‘gatekeepers’. They may block or expedite access to public services based on the payment of a fee based on his/her special position as an access provider (Kumar & Landy, 2012: 130-131). Brokers and other such informal networks effect a new understanding amongst citizens seeking to make use of public services – that services are out of reach for citizens if not for them.

With respect to the citizen services at South and North Municipalities of Delhi, service seekers had trouble finding their way in the maze of departments, and thus preferred approaching the broker sitting outside to optimise their use of time (based on quantitative survey of service seekers) at a nominal fee. The officers within the institutions viewed these brokers as a complementary part of service delivery. The brokers themselves however felt that they should be institutionalised as service partners due to the high volume of services seekers, usual technical glitches, steep learning curve for officials to keep up with systemic interventions, and the general acceptability of the public as long as they don’t feel harassed by them.

The three perspectives point to a gap in the accountability of service providers to citizens, and the attempt of citizens to question the former on deficient or delayed service delivery.

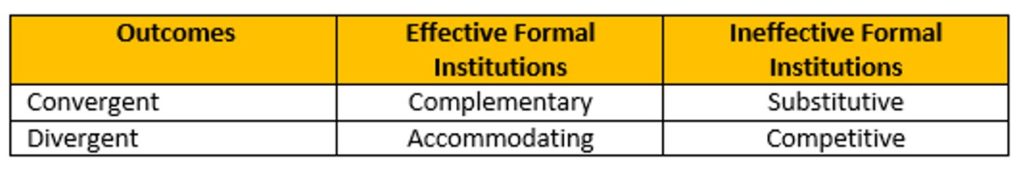

The Helmke & Levitsky (table below) framework offers an understanding of the linkage between informal institutions and formal government systems.

The typology provided by Helmke and Levitsky (2004: 728) is based on the outcomes of informal rules and effectiveness of the formal rules in a given context. The outcome variables dictate whether the result of these rules are in line or against what one may expect from strict adherence of formal rules. The effectiveness variable on the other hand is the extent to which the formal rules are realised in practice. It is understood that, where the rules and procedures are ineffective, the probability of enforcement will be low (Helmke and Levitsky, 2004: 728).

The study findings based upon service-seeker surveys & interviews confirmed a direct dependence on these brokers outside any and every municipal office in New Delhi. A sample of 30 service seekers across two municipal zone offices conveyed that 80% of them usually approached brokers to speed up the process of their work at a minimal fee irrespective of their economic status. While the less educated clients seemed more vulnerable to exploitation, the educated, upper class clients too waited for their turns for calculation of property tax, if not for arrangement of paperwork to obtain birth/death certificate. When the corresponding public official was asked about a possible institutionalisation of these service providers, it was an easy ‘no’ considering there was no incentive to engage in process reformation, unless nudged by the concerned administrative reforms department.

“It could be you helping them (service seekers) out with paperwork, at a fee or not is none of our concern. In my opinion we are well equipped to serve everyone who come work any work and if these people (brokers) think they can expedite their job, and if the clients engage, it is their choice. I still don’t think there is any mistrust or capacity issue” – A health official, Zonal Office, North Delhi Municipal Corporation

In my research, the modus operandi of broker-led governance was further mapped against the recent doorstep delivery of public services policy initiated by the Government of NCT of Delhi (GNCTD) to understand the inherent complexities in the system of delivery of public services. The doorstep delivery of public services was a set-up where mediation was institutionalised as part of the system to prevent exploitation of service seekers by the brokers, who established ‘temporary power centres’ (Media reports in 2017-18).

The study further triangulated effects of patronage-led mediated governance on how current practices fare along the good governance principles of state’s accountability, transparency, effectiveness and efficiency (UNESCAP: 1 & Gisselquist, 2012). Mediated governance has no accountability to its users but brokers are usually risk averse and efficient in delivering services to ensure the leverage of positive marketing and maintaining their space in the ‘mediation market’.

In other words, the system is far from being transparent as nobody knows the legitimacy of the means used by fixers. The mediation of public services may well be offering services to citizens at a price in the short-term, but it is a larger reflection of the lack of capacity, complacency and poor design of service delivery systems in the long-run.

References

Gisselquist, R.M. (2012) Good Governance as a Concept, and Why this Matters for Development Policy. WIDER Working Paper

Gupta, A., 2012. Red tape: Bureaucracy, structural violence, and poverty in India. Duke University Press.

Helmke, G. and S. Levitsky (2004) ‘Informal Institutions and Comparative Poli-tics: A Research Agenda’, Perspectives on politics 2(4): 725-740

Kumar, G. and F. Landy (2012) ‘Vertical Governance: Brokerage, Patronage and Corruption in Indian Metropolises’, ‘Vertical Governance: Brokerage, Patronage and Corruption in Indian Metropolises’, Governing India’s Metropolises, pp. 127-154. Routledge India

About the Writer

Sushant is a Senior Programme Officer at Accountability Initiative.