School Consolidation: Catalyst for Change or an Inequitable Policy?

25 September 2019

Improving learning outcomes are the principal focus of contemporary education policy in India. There are numerous ways to achieve these outcomes, many of which were identified in the Right to Education Act (2009). With the implementation of the Right to Education, the inputs supplied to schools such as teachers, space, meals, and educational materials have increased. Yet, several concerns have been raised over efficiently allocating resources to improve access for students and quality teaching.

In the context of weak state capacity and limited resources, school consolidation has emerged as a policy tool with a view to improve the efficiency of school functioning. This refers to the ‘closure’ of one or more schools and integration with another, usually bigger school. Students and teachers are transferred to the consolidated school, if space permits. The schools that are closed no longer exist as independent administrative units.

School Consolidation in Rajasthan

While schools have been consolidated over the years across many countries including China, Canada, and the US, this policy tool is relatively new to India. Faced with poor learning outcomes, declining enrolment in government schools, and the proliferation of small schools with poor facilities, the Rajasthan government was one of the first Indian states to consolidate schools. At the same time, the Rajasthan government launched other programmes such as the State Initiative for Quality Education, and programme to create Adarsh schools with grades 1-12 or 1-10. Something similar to the latter has been mentioned in the hotly contested National Education Policy as well, which talks about the creation of school complexes or multiple schools together as a single administrative units. These Adarsh schools or complexes can be created by consolidating schools.

Around 19,500 government schools were consolidated between 2014 and 2018 in Rajasthan, and other states such as Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra followed suit. In 2018-19, the Accountability Initiative analysed secondary data to understand the implementation and short-term effects of consolidation in Rajasthan.

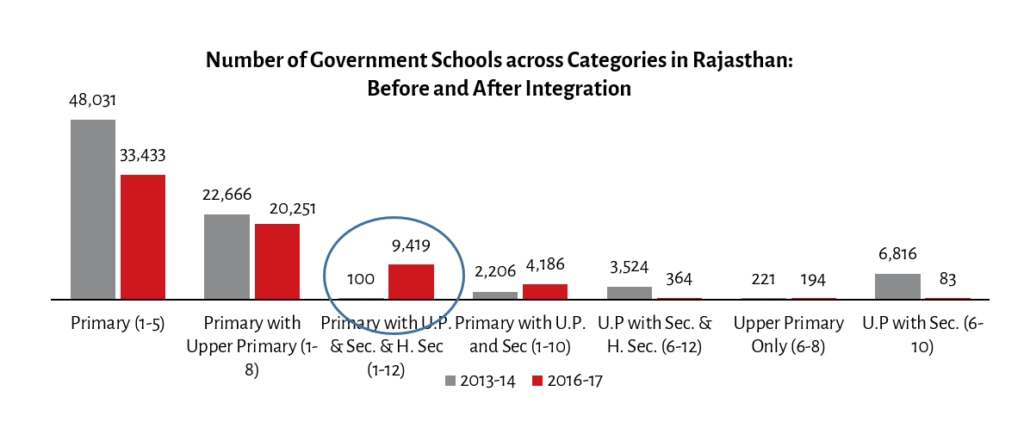

To create Adarsh schools or large schools, the bulk of consolidation, especially in 2014-15, typically involved the closure of elementary schools (grades 1 to 5, grades 1 to 8, or grades 6 to 8) and their consolidation with secondary schools (with any grades from 9 to 12). However, elementary schools were consolidated with other elementary schools as well, especially in 2016-17.

The reorganisation of schools in this manner can impact the education system in the long run – it can change the number of teachers available, administrative and monitoring structures, resource-use, etc. In short, at scale, school consolidation can shake things up. From our study, we found that schools were reorganised quite substantially, with the number of schools with all grades increasing significantly as can be seen in the graph below.

The RTE clearly states that schools need to be easily accessible. Specifically, primary schools need to be within 1 km radius of the child, and upper primary schools need to be within 3 kms. The Rajasthan government too followed this norm.

Therefore, we asked two primary questions. First, has consolidation changed the availability of teachers, school facilities, monitoring, etc.? Has it made the system smoother in any way, eventually benefitting children? Second, did this make a basic service guaranteed by law, inaccessible to certain people? Has it led to people having to drop out of government schools and shift to private schools which are more accessible for them?

The availability of teachers and facilities improved, but elementary schools lag behind

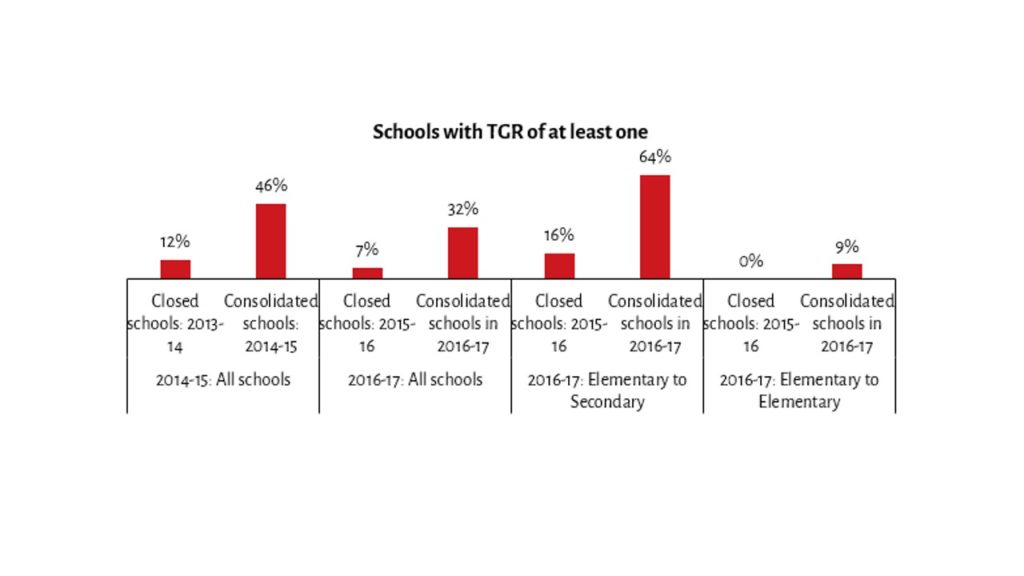

Before consolidation, the teacher-grade ratio (TGR) or the number of teachers divided by the number of grades was low (3 teachers for 5 grades, on average), despite a healthy pupil-teacher ratio. For example, in a school with 30 students, 5 grades, and 2 teachers, the pupil-teacher ratio is 15, well within norms. Yet, 2 teachers have to work with 5 different grades, which results in multi-grade teaching. Often, students of different grades are seated in the same class and taught together and students receive less attention and care than needed. Furthermore, 16 per cent of all government elementary schools in Rajasthan had only one teacher.

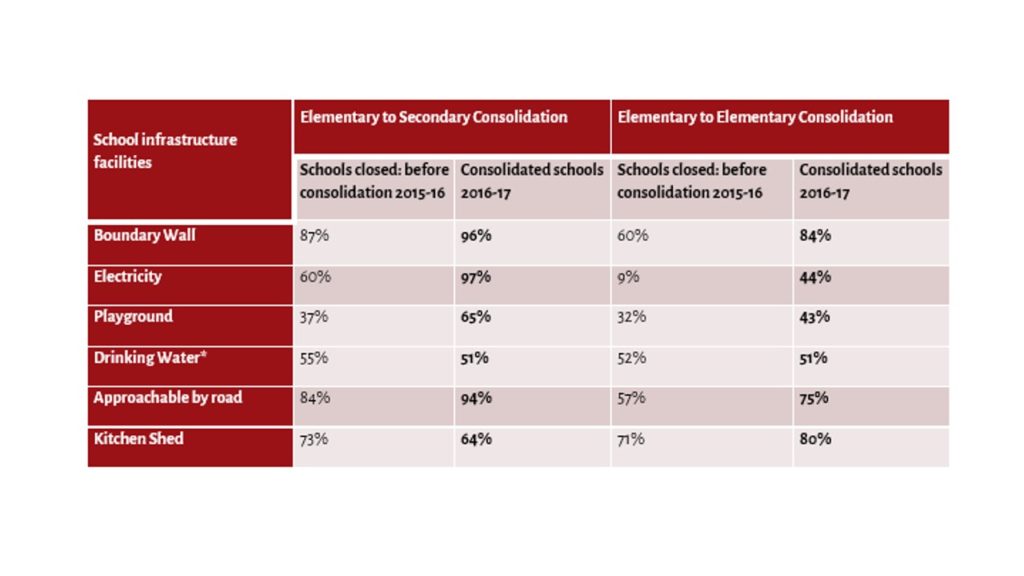

Ideally, a school with 5 grades should have at least 5 teachers, or a teacher-grade ratio of at least one. After consolidation, secondary schools had more teachers for every grade. We can see that for schools consolidated with elementary schools, the improvements were small. In fact, the TGR for these schools was around the state average, while secondary schools pulled ahead.

In terms of facilities like a playground or a boundary wall, access improved for students whose schools were consolidated with secondary schools. However, elementary schools lagged behind again.

Did school consolidation lead to dropouts?

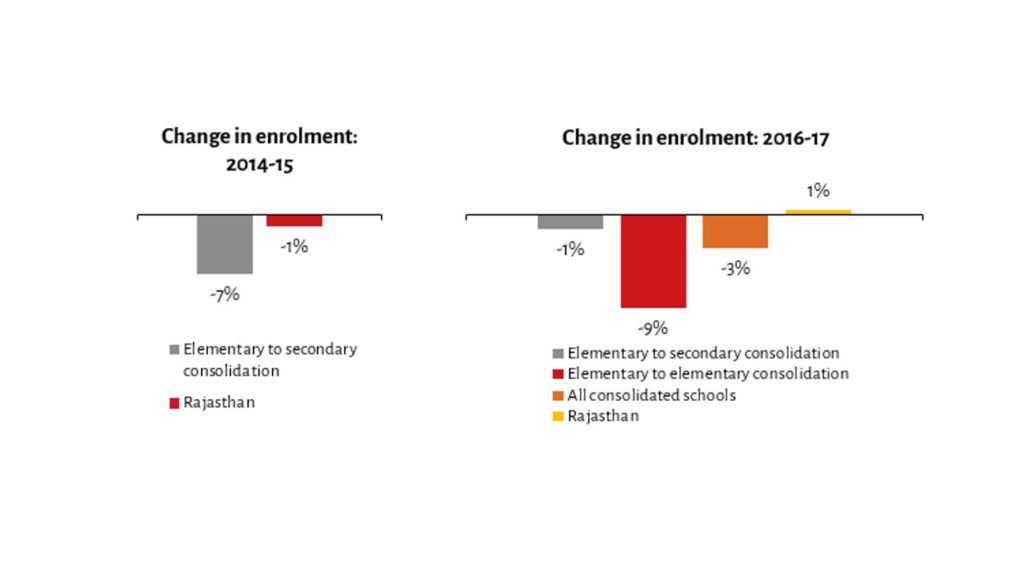

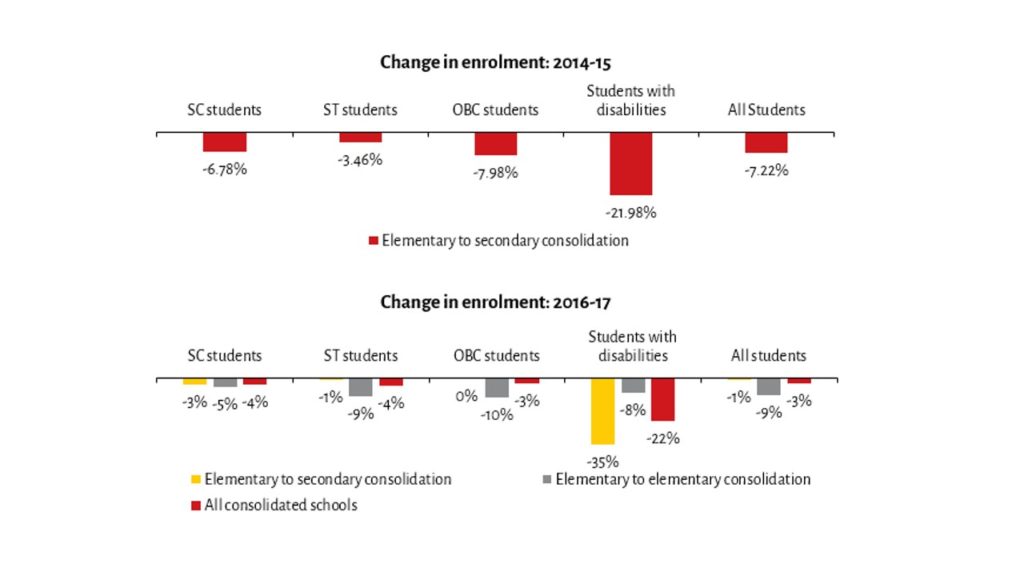

We looked at the combined enrolment of schools prior to consolidation, and the enrolment after schools were consolidated. Enrolment in Rajasthan did not change much over the years, but enrolment declined in consolidated schools, across all social groups. Did enrolment decline due to consolidation? Were people excluded? Certain reports definitely argue that this is the case. However, since we looked at the short-term effects, further inquiry is merited to understand the specifics of this decline in enrolment.

Particularly hard hit were students with disabilities, likely due to increased distances to schools. When elementary schools were consolidated with secondary schools, the enrolment of students with disabilities declined far more than other groups. Did parents of other students feel that their children should go to secondary school with potentially more teachers and better facilities, even if further away? It is possible that increased distances for students were mitigated by the expectation of higher quality.

On the other hand, when schools were consolidated with elementary schools, the decline for all groups is the same. Perhaps elementary schools lagged behind, and an increase in school distance was not compensated by an increase in quality, explaining the decline in enrolment.

Given that enrolment declined, a natural question is – was the way these schools were chosen for consolidation a factor behind the drop? Broadly, the following process was followed. Officials at blocks selected schools, which were aggregated at the district level, and verified by the state departments. Subsequently, after verification, the state passed orders to districts and blocks to consolidate schools. Teachers, parents or guardians, and local leaders were not consulted. Top-down or non-participatory planning is nothing new. However, the consolidation of schools was reversed in several instances due to various reasons, including high SC/ST enrolment in the schools shut, adequate enrolment in the schools shut, political pressure, and so on.

What next?

To the extent that more teachers are available, consolidation can set the stage for improvements in learnings. Nonetheless, it is too soon to say that consolidation improves teaching and learning practices. Questions of equity remain. School consolidation seems to have had a different effect across elementary and secondary schools, and students in the former could get left behind. At a time when over 40 per cent students in government schools in Rajasthan are enrolled in elementary schools, there is a need to improve teacher availability and facilities in these schools too. Consolidation has the potential to bring about substantial changes in the way the school system is organised and administered, but community participation, equity, and access to all should underpin any such transformation as we move forward.