Grievance Redress: Arriving at an impasse?

23 June 2014

The Right of Citizens for Time Bound Delivery of Goods and Services and Redressal of their Grievances Bill (RTRG), 2011 was initially proposed with the aim of granting time- bound delivery of goods and services. The Bill also established Citizen Charters that create a workable interaction between the government and citizens to tackle implementation- related grievances. This bill sought to answer some vital questions of how a grievance should be made, how the relevant department can solve the grievance, measures to ensure timely response of a grievance and finally, a solution to the grievance asked. It has generated considerable debate on service delivery and accountability, and is known to have initiated the creation of Citizen Charters across government departments. These charters are not only directed to every public authority across all states[2], but have also become fundamental to lessening the communication gap between the government agency and the citizen (you can view an example of a Charter here). As seen in the attached link, the Department of Rural Development’s Charter lists out details such as services offered, quality of the service, and timeline of service delivery. Several models have come up based on this format- the Sevottam and the e-Abhijoga are a few examples of these variants.

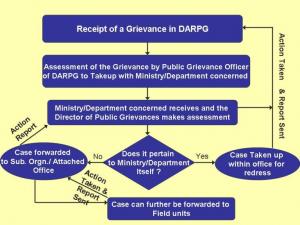

So how does a typical grievance travel from the citizen to the government machinery? A visual of this can be seen below:

(Source: Directorate of Public Grievances, dpg.gov.in)

So, if a complaint is made to the Department of Rural Development on the non-disbursal of month-wise amounts within MGNREGA for a particular beneficiary, it will first go to the DARPG- (the over-arching Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances that overlooks all grievances), will be taken up by the Public Grievance Officer who will then send it to the Department/ Ministry concerned. As seen with the image, action taken and reports that are send follow a structure that visually makes sense.

There are four key characteristics of the Grievance Redress process:

a) The entire complaint process consists of three stages – the submission of the initial application, first appeal and the second appeal.

b) Each process has designated officers who receive and review the new applications, in addition to doing a preliminary check on whether to approve a particular service in a prescribed time limit or reject the application entirely (but, with proper justification stated).

c) In-built in this system is the assured element of time. Within two days of the complaint being registered (at the district kiosks or online), citizens who have filed a complaint will receive (this is usually done by SMS or mail), a unique complaint number and a time frame within which the complaint will be handled- this is limited to 30 days. This means that within 30 days of sending in the complaint, a response / solution needs to have been made by the First Appellant Officer. The processes within this time frame are given in the image above.

d) The last point is on the parallel communication processes that take place between the government Departments – i) The Department that receives the complaint (and officers within) and ii) the Department that the complaint is for, the officers within and iii) the specific local officials who were delivering that particular service.

The process seems to be fairly simple, and structured well enough to actually work to a great extent. However, there are several challenges that one faces once a complaint is sent, some that are not apparent in this particular visual, and therein lies the rub.

The mandatory nature of the Charters has generated questions regarding levels of acceptance across states. . There is unevenness in the creation of Citizen Charters across states with some states (Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh) that already have implemented Citizen Charter Acts or Public Services Guarantee Acts. Making this mandatory for all states is not the same as ensuring that it has been created and is an effective system of redressal. This is the first step and also the first challenge. There are large variations in the uptake of not just the Citizen Charters but also the push towards e-governance with some states performing better in terms of their response to requests for redress, and with other states providing more than the basic services on their platforms.

Second, when Madhya Pradesh became the first state in India to enact Right to Service Act in 2010, there arose another layer to the accountability framework- that of checks and penalties. However, across states today, penalties are another inconsistent feature. A preview of the penalty range across states is given below:

| State | Total penalty imposed |

| West Bengal | Between Rs 250- 1000 |

| Punjab | Between Rs 500- Rs 5000 |

| Assam | Between Rs 200- 2000 |

| Orissa | Between Rs 250- 5000 |

| Kerala | Between Rs 500- 5000 |

| Madhya Pradesh | Between Rs 500- 5000 |

They range from Rs. 250 to a maximum of Rs. 50,000 a day (as mentioned in the RTRG Bill) and are imposed on officials who have been identified as having failed to deliver services in time. There is little information available in the public domain on what comprises of a failure, whether there are varying fines for higher or lower officers, and the impact of this wide range of financial penalties on officers. Questions on whether it has any impact at all remain largely unanswered- are officers more prone to work towards timely services if they are fined?

Third, is an additional communication haziness in the organizational arrangement of grievance redress, especially since it concerns not just the DARPG but also each Ministry to which the complaint is addressed to. Are the ministries/department to which the complaint is directed to have a time limit to their responses? Who monitors this?

Being an example of what Teubner theorized as a flexible reflexive law [3], the RTRG Bill does not bring in new concepts, but is at the forefront for formalizing a rights- based governance structure that builds on installing mechanisms of accountability which ties public services directly with the hands of the people. This Act sought to become the backbone for grievance redress as a Right to the citizens. However, the final challenge it faces is its obscure future. With the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha on 18 May 2014 by President Pranab Mukherjee, the direction of this Act is ambiguous. Now that it has lapsed, will swift decisions be taken this year? Only time will tell.

[1] Lant Pritchett. 2009. Is India a Flailing State? Detours on the four way highlane to modernization. http://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/4449106

[2] PRS Legislative Brief. http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Citizen%20charter/Legislative%20Brief%20Citizens%20Charter%2027%20Sep.pdf

[3] Reflexive law is that which ‘restricts itself to the installation, correction, and redefinition of democratic self-regulatory mechanisms’.

Teubner, Gunther. ‘Substantive and Reflexive Elements in Modern Law. http://ssrn.com/abstract=896509