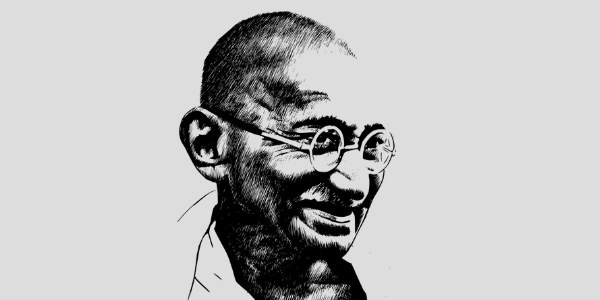

Swaraj and Urban Governance: Remembering Gandhi

2 October 2020

‘India lives in its villages,’ said Gandhi.

And from that observation, as well as many others where he envisioned a future India built on a foundation of self-reliant, confident rural communities, the general impression that we have of Mahatma Gandhi is that he was anti-city, anti-industry and yearned for a simple, improbable utopia of bucolic bliss.

Wrong.

Mahatma Gandhi’s life and work was indeed forged and fortified by his life and work in cities. As eminent scholar Ramachandra Guha observed (“The cities that shaped Gandhi, the cities that Gandhi shaped” by Ramachandra Guha published in the Hindustan Times in 2019), many of the defining moments and movements in Gandhiji’s life occurred in cities. He was educated in London; he cut his political teeth in Durban and Johannesburg, he established the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, he fasted for communal harmony in Calcutta, and eventually, sadly, was assassinated in Delhi.

As India continues relentlessly on the path of urbanisation, Mahatma Gandhi’s observation that we live in our villages, is now a cry in the wilderness. One might say that the push towards cities has been driven by overpopulation and the inability of villages to offer a life of prosperity to people. However, that might not be entirely true.

Even those states that have arrested population growth and which may be in a situation of population decline with an inexorably aging people, are becoming urbanised. Tamil Nadu and Kerala, are today some of the fastest urbanising states in India, if one discounts the smaller states and Union Territories such as Goa, Puducherry and Delhi. Urban life is not only appealing from the point of view of more work opportunities; they also offer greater access to healthcare and more comfortable housing (at least for conventional thinking people).

It is paradoxical that elements of people’s participation through the institution of the Gram Sabha are captured in the Constitution and made applicable in rural areas, whilst there is no corresponding structure for peoples’ participation in urban areas.

Yet, our cities are unjust. People who have left their villages to live in the cities, chasing their individual dreams, live in conditions that may be far worse than they are back home. Inequalities are rampant; pollution and lack of access to clean water drive death and disease. Still, that does not detract from the attraction of the cities for those desperate to escape from an oppressive social reality that is the state of life in our villages.

What might Gandhi have made of our rampant urbanisation? What would he have thought of our slums, our dysfunctional urban services? What advice would he have given us, watching our predicaments in cities? What would he have done during the pandemic, when the rich shut themselves away in their gated communities, leaving the poor to fend for themselves, and find their own ways back to their homes in their villages?

Taking lessons from these social disasters that followed in the wake of the pandemic, what can we do to make our cities more compassionate, inclusive, more equal and just?

If Gandhi were around now, I am sure he would have argued for urban villages, envisioning our cities as a federation of thousands of small communities, each self-sufficient to the extent possible, taking care of its environmental needs, conserving its resources, and engaged in self-rule.

Sadly, our cities are the very antithesis of that vision. It is paradoxical that elements of people’s participation through the institution of the Gram Sabha are captured in the Constitution and made applicable in rural areas, whilst there is no corresponding structure for peoples’ participation in urban areas. This deliberate disempowerment of people in urban areas, the breaking down of urban social structures and the rejection of community collaboration is a rejection of Gandhian ideals.

On the other hand, would the idea of self-ruling urban communities sail in today’s interconnected world? The answer to that question is tricky. It cannot be presumed that a self-ruling local community is ipso facto just and inclusive. Self-rule throws open the risk of local authoritarianism finding legitimacy; with people’s participation only being used by the local despot to endorse his authority.

We must remember that many of those who come to urban areas seek solace in the anonymity that a city provides, in which social barriers can be forgotten and people can strive to prosper, unhampered by hierarchies that tie them down to their caste or their gender, in rural areas.

I often imagine myself having arguments with Gandhiji in today’s milieu. I assume that Gandhiji would argue for urban Swaraj through self-ruling communities. I would totally agree with him that his village Swaraj concept, applied to urban areas, is the best way to solve chronic urban problems such as sanitation, provision of health, education and nutrition.

Yet, I might oppose that idea being carried to its logical conclusion. I would argue that such self-ruling communities will have a tendency not to uphold the idea of individual liberty. I would emphasise the point that collective decision making might fortify prejudice and prevent individuals from enjoying their freedoms.

Would Gandhiji agree with my points? I am sure he would give me a patient hearing. He would listen avidly, I imagine, as I tell him that I am arguing these points by assuming the role of a devil’s advocate.

Of one thing I am sure. He will not say that I am anti-national. He will not attempt to shut down my voice. He will not send the police after me.

I have set the bar low, therefore, on this Gandhi Jayanti.

To my fellow citizens all that I plead for today is this much; let all of us be given the space to speak, to protest, without being intimidated on the basis of religion, caste or gender, or being told that to protest itself is anti-national.

T.R. Raghunandan is an Advisor at Accountability Initiative.