All too many School Inspectors saying “all is well”?

24 January 2011

Teacher absenteeism has been documented to be widespread and while the motivational reasons and drivers of this are complex (Ramachandran et al, 2005; Kremer et al., 2004), one factor that has permitted this is weak supervision or absence of inspections. Monitoring providers of services to hold them accountable is an important part of any service delivery system. Governments have acknowledged this and inspections have been taken particularly seriously by the government primary education system of Madhya Pradesh (MP) I recently visited (and more generally across states by the centrally sponsored Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan scheme). Has it worked? On paper at least, it has. Assigned to undertake inspections of teachers in schools within a district are the following list of officials in MP: the Cluster Academic Coordinator (CAC or Jan Shikshak), the principal of the Higher Secondary School who functions as Cluster Drawing-Disbursing Officer (DDO), the Block Education Officer (BEO), Block Academic Coordinator (BAC), Block Resource Centre Coordinator (BRCC), Assistant Project Coordinator (APC) at the district-level, District-Project Coordinator (DPC), District Education Officer (DEO) and his Assistant, the Joint Director (JD) as well as the CEO Block and CEO District from within the Rural Development Department. Considering that there are usually 3 BACs in any BRC Office, 4-5 APCs at the DPC Office and several more CACs, the number of officials functioning as inspectors at any block or district are consequently many more. Do teachers however feel that they are functioning in an Inspector Raj system? Thankfully for them at least, this is not necessarily the case.

The reason is that in practice not all officials are able to meet their inspection targets or make the time available for travel to undertake inspections at the cost of other work they are also tasked to undertake. For, of the list of officials mentioned, much fewer of them (CAC, BAC, BRCC) are in fact tasked principally with the inspection responsibility. The challenge then is not that inspectors do not exist or have not been assigned duties with clear formats; rather the challenge is inadequate implementation of inspectorial duties. The obvious question that then comes to mind is this: who inspects the inspectors?

There was for a long time a single vertical structure that made answering this question somewhat easier. From the Zila Shiksha Basic Adhikari to the Sub-Deputy Inspectors of Schools, each district used to have one line reporting structure. With the District Primary Education Programme (DPEP) of the 1990s that was scaled up to the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), a separate vertical of contractual posts was also created that covered monitoring functions.

Parallel to the existing administrative system in the state, this implementation of the now decade-old SSA has consequently created a separate management structure engaged in supervisory activities as well. Drawing attention to this two-dimensional system currently present, the recent Anil Bordia Committee has proposed integration of educational administration at different levels. This same report notes that during the last few decades “school supervision has grievously suffered due to insufficiency of staff and administrative neglect”. While acknowledging that the SSA may have “improved matters”, it still concluded that “the situation has remained essentially unchanged” and more damningly that “the functioning of schools has deteriorated and quality of the teaching-learning process has shown no improvement” (Bordia Committee Report, p.83). The solution suggested: better supervision and more periodic inspections.

In MP recently to develop a PAISA Tool for institutional analysis, I found in fact three vertical structures existing. Why does this adversely effect inspections? To illustrate: if the present full-time inspector in the Jan Shikshak (CAC) finds an incidence of teacher absence in a school, this is reported to the BRCC, which moves further up the same vertical to the DPC, who then reports this absenteeism to the DEO in a different vertical. But in order for any action on the concerned teacher, the DEO must report the same to the District CEO from yet a separate vertical (Rural Development Line Department), who is the designated appointing authority of the teacher and the only official with the powers to terminate the appointment. The length of steps to reach the appointing authority translates into a time lag between an inspection and any action. This may be further delayed because the CEO orders his own inspection or simply because he is in-charge of 21 divisions with Education being only one of these. Secondly, the Jan Shikshak can draw his pay from the BRCC by reporting “all is well” from all his required quota of inspections, which is an incentive that also drives the BRCC to report “all is well” as he too has 30 inspections to complete in a month alongside attending mandatory official meetings and other work to draw his pay. The “all is well” mantra popularized by a recent Bollywood film therefore keeps everyone in the system happy, from the Jan Shikshak and BRCC to the teacher and anganwadi worker in this collusion.

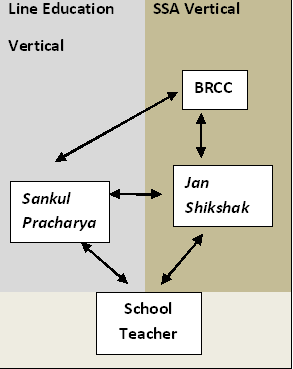

Interestingly, a way to bring better accountability to the inspections of the Jan Shikshak is not to wholly change the current arrangements, but to modify it in important ways. At present, officials in different verticals do not hold the other accountable to the extent they potentially can. The Sankul Pracharya is the Principal of a Higher Secondary School who is the Drawing & Disbursing Officer paying teacher salaries for a designated number of 7-8 schools in the area. He falls under the Line Education Department vertical. Currently no rule states that the Jan Shikshak (a SSA vertical officer) must a priori inform the Sankul Pracharya of his inspection schedule of the schools in his purview so that the latter can hold the former accountable for having undertaken them. Nor is the Jan Shikshak also reporting his inspection findings to the Sankul Pracharya, who can then use the report to cut the wages of absent teachers, which he is authorized to carry out with evidence. If the BRCC (also a SSA vertical officer)was further required to have a mandatory countersign of the Sankul Pracharya as a precondition for releasing pay to the Jan Shikshak, there is a further built-in “triangulating” accountability measure of the inspections having been undertaken as planned and the information shared for necessary immediate action on absent teachers through docking wages. The BRCC can then even hold the Sankul Pracharya accountable.

Triangulating Reporting for Better Accountability

The lesson I took away from MP is that rather than creating more inspectors higher up the vertical who find themselves too busy with routine other work to travel for inspections, there is a case to be made for many more Jan Shikshaks. Unlike the present system, their sanctioned numbers at the block-level should be determined by a fixed ratio to the density of schools in the area to be monitored. We need more full-time inspectors who are held more accountable for their work.

Finally, can the inspector of inspectors also be at times from outside of the government system? The 1954 ‘Report of the Committee on the Relationship between State Governments and Local Bodies in the Administration of Primary Education’ was categorical that “all inspecting officers should be directly under the government and that the Local bodies should have no control over them” (1954 Report, paragraph 61). In the changed circumstances of today when we have an active Rights-based movement and the 74th Constitutional Amendment, it will be interesting to see whether in practice envisaged local bodies such as the School Management Committees will be empowered to hold inspectors accountable. Or would the Committee Members of the 1954 Report, if still alive, have not much change to worry about.

Shomikho Raha is Lead, Implementation Research at the Accountability Initiative.