Data Governance and the mythical character of a ‘Data Scientist’

29 October 2012

On Thursday, October 18th, I attended a seminar on “Open Data for Development” by Shaida Baidee and Neil Fantom, director and manager respectively of the Development Data Group at the World Bank . The presentation was fascinating, and the range of work that has been done by the World Bank is frankly quite astounding! From making their vast databases public in a easy to navigate format, to creating micro-data explorers that can help other researcher play with micro-data, their products seem to have covered just about everything. After they made their presentation, they were asked a number of questions by the participants. I have categorized all questions under the following heads.

Vision – What was the driving force behind the data group?

Business case – “How do you measure your Return on Investment? Clearly, there is a loss in revenue if you are no longer selling data, but putting it out for free. In addition, you are also investing a lot more to maintain a data platform. How do you measure return on this investment?”

Policies – What won’t you put on the website? What makes a country a good candidate or a bad candidate for opening up their data? What are some of the bad effects of putting data online and how can we manage those risks?

Change Management – How did you encourage researchers within the team to put their data up online?1

People – How do you nurture the wider hacker community to engage with your data? How do you engage the wider community for whom the data is meant? What is your in-house capacity to do these things?

These questions are not new. In fact, the repetition of these set of questions by different stakeholders – government officials, non-profits, industry experts, organizations etc at almost every open data meet I have attended indicates that we still haven’t found the correct framework in which to think about data. According to me, all the above categories are inter-related and point to the fact that one needs to take a systems approach to data – essentially, think about ‘Data Governance’ on the whole, rather than any individual question.

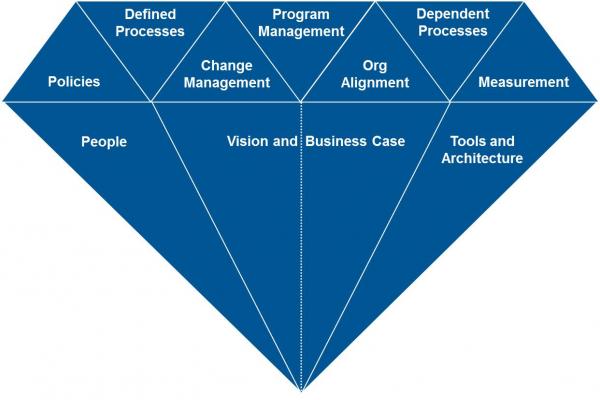

The paradigm shift is subtle but very profound. It means not thinking about data alone and the shiny things that can be done with it. Rather one should be thinking about the organizational goals, assets, processes, decisions and stakeholder interactions that data needs to enable. To give you an analogy – when you buy a piece of furniture for your home, you take into account how well it would go with the colors of your house, how well it serves the seating needs of your family and so on. It’s never a decision independent of those factors. Similarly for data. It needs to be thought of against the wider background of the organization. And that’s where a data governance framework helps, of which there are quite a few. The one I found very comprehensive and visually appealing was the one by Informatica, a quick introduction to which can be found here and the visual itself can be found below.

While each of the above facets are equally important to ensuring data’s value, I would like to elaborate on just four of them.

Policies – Increasingly, I find open data policy being pushed as the only possible policy option for governments and non-profits. Having played with open source before, I can see the potential of applying its principles for data, but the evidence is sketchy. For governments, the ethical case seems strong (public data for public good) and there is some evidence of its advantages2. However, in the case of non-profits, especially smaller research-organizations, the business case is very unclear.

Leaving the open vs limited vs closed data policies aside, it’s important to have a detailed data policy in place, and not just as a footnote at the final stage of publishing. This policy needs to talk about issues like data accountability and ownership, organizational roles and responsibilities, standards on data storage, archiving, access, usage, privacy and security and it needs to guide all team-members from the very beginning of a project.

Dependent Processes, People and “Tools and Architecture” – I am taking these three facets together as I believe they are intermeshed. The Informatica blog puts it very succinctly “You can’t govern data until you first understand the life cycle of the data.” For example, for a financial organization, it might be important to keep financial records untouched for 7 years or more due to regulations3. Such organizations should ensure that their data-locking processes are strong. For a research organization, it’s important that the research results are reproducible, hence its important to make sure that all Stata commands used to reach a result (usually documented in do-files) are well-documented. Data processes thus vary according to organization. Below I have mentioned two factors that might help you catalogue your data processes.

- Secondary vs Primary research: The starting point of the data life cycle is different for organizations working with secondary and primary data. The former need to start with good, clean data-sets. They thus need to think about things like scraping, database access through programming, political wrangling with departments and so on. Primary research organizations on the other hand need to invest in processes for creating good, clean data-sets4.Organizations like ours which work on primary and secondary data need to think even more deeply about their data life cycles.

- Amount and velocity of data: Data processes also depend a lot on the amount of data available. The latest buzzword in the data world in ‘Big Data’ – in simple words, when the amount of data becomes large enough for an organization to start worrying about the bulk, it is referred to as Big Data. Forbes in this article has referred to a Gartner Research (subscription required) which splits the advantages of working with big data by industry. Governments feature very prominently in it. And this makes sense intuitively – governments have vast amount of data, and keeping track of them is a task in itself. In fact, seeing the potential of big data analytics for improving governance, the UK government is in talks with Cloudera, a distributor of Hadoop-based software for working with big-data.For research organizations looking at just limited number of government data sets, the amount of data is of course much lesser, and for efficiency purposes the processes need to be tailored to that amount. However, if the target is to improve government’s data processes, it’s important to keep abreast of ‘Big Data’ tools and trends.

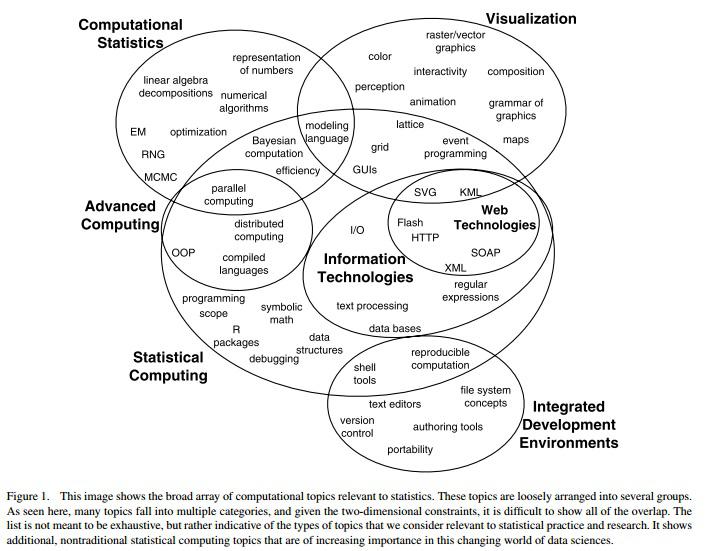

Once the data life cycle in an organization has been identified, the next step is to match people and tools to various steps in it. The Informatica blog talks about hiring ‘Data scientists’ if data forms a major part of an organization’s work. However as I have seen in AI’s work, the skills required of a data scientist are so many that they almost sound like mythical characters5. They combine domain knowledge with hacking skills, math and statistical skills6 and storytelling skills. This visual below taken from “Computing in the Statistics Curricula” breaks down the skills required of a data scientist. Mythical character, I heard someone say?

In my opinion, a better way to think about data-scientists is to think of a team of people with varied skills, who would collectively form this mythical character. The challenge would be to ensure that people talk each other’s language – a person with visualization skills should be able talk to one with statistical skills who can talk to one with computing skills, who can then talk to somebody with just domain knowledge. That I believe is the challenge any organization’s data-governance group would need to figure out.

In conclusion, I believe organizations need to move away from thinking of data as a stand alone good, but rather think of it as one of the many assets an organization has that needs to be managed strategically to ensure maximum value.

1According to Hans Rosling, they have a Database hugging disorder.

2For governments looking to create their Data Policies, this might be of interest – UK Institutional Data Policies

3The Sarbanes Oxley Act was enacted as a reaction to a number of corporate and accounting scandals. It mandates that the integrity of financial records be maintained for not less than 7 years.

4Before Data Analysis begins, Ambrish Dongre

5In fact, the Harvard Business Review has gone as far as saying that a data scientist is the sexiest job of the 21st century. http://hbr.org/2012/10/data-scientist-the-sexiest-job-of-the-21st-century/ar/pr

6The Data Science Venn Diagram – http://www.drewconway.com/zia/?p=2378