Decline in Unemployment Rate in 2020-21: A Reason to Rejoice or Worry?

18 July 2022

The newly-released Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), 2020-21 documents an important employment trend. During the one-year period between July 2020 (3 months after the first COVID-19 wave hit the economy), and June 2021 (when the economy started reopening after the second wave of the pandemic), India’s unemployment rate registered a decline as compared to the same period in the previous year (July 2019 to June 2020). Were there actually more gainful employment opportunities generated in 2020-21? An analysis reveals that most people were taking up distress employment for sustenance, which is concerning.

The decline in unemployment came in comparison to an already difficult unemployment situation faced by the country in 2019-20. This welcome reduction documented in the PLFS is a surprise as the employment woes brought on by the pandemic are still very fresh. Starting from the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns in March 2020, economic activities across the country were severely hit, multiple times throughout 2020-21. This had a direct impact on India’s highly informal labour market.

For instance, not only were there job losses, but also income-cuts for a considerable section of the workforce. According to monthly estimates published by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), unemployment rates touched very high numbers, ranging from 21.7 per cent in May 2020 to 11.8 per cent in May 2021. Once the nationwide lockdowns that began in 2020 were lifted, the economy rebounded.

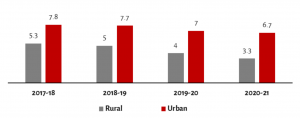

The overall unemployment rate, as per PLFS data, declined slightly from 4 per cent in 2019-20 to 3.3 per cent in 2020-21 in rural areas, and from 7 per cent to 6.7 per cent in urban areas (Figure 1). As a result, the worker population ratio (WPR) or the proportion of the population who were working, went up from 38.2 per cent to 39.8 per cent during this period. When disaggregated by gender, there was a higher percentage point increase in WPR for females which increased from 22 per cent to 24 per cent, as compared to that for males (54 per cent to 55 per cent).

Figure 1: Unemployment rate (in percentage points) considering usual principal and subsidiary status (UPSS), All India

Note: Usual Principal and Subsidiary Status’ (UPSS) considers workers according to both principal status (those working for a relatively long part of the 365 days preceding the date of survey, as well as subsidiary status or those persons from among the remaining population who had worked at least for 30 days during the reference period of 365 days preceding the date of survey).

The decrease in unemployment rate can be seen as a reason to rejoice as it is an indication that more people got the opportunity to enter the workforce during the one year that followed the first wave of the pandemic.

But here’s the catch.

A deeper look into the nature of employment reveals that there was actually a shift towards more precarious and informal types of work such as informal self-employment and unpaid work in family-based enterprises, than people engaging in sustainable and gainful employment. There was an overall increase in the share of own-account workers who operate by themselves, with or without business partners, and without hiring any labour. At the same time, the other vulnerable category that registered an increase in employment share was unpaid workers who helped in family-based enterprises, but did not receive any income for their work.

While the share of casual labourers did not change much, those earning regular salaries came down substantially. This reflects a rise in the levels of informality and precariousness in India’s labour market in 2020-21 against the backdrop of a slight decline in unemployment rates.

Moreover, the situation seems to have worsened for women. Even though women’s overall WPR went up, a large portion of them was engaged in precarious work causing significant vulnerability and uncertainties for sustained livelihoods. Among all women workers, the share of unpaid helpers in family-based enterprises rose from 35 per cent to 36.6 per cent (Figure 2). For women working without earning an individual income, there was obviously little scope of economic independence or empowerment.

Similarly, the share of women who were self-employed and mostly worked on their own small family-based enterprises, went up as well. Even more worrisome, the proportion of women engaged in regular-salaried work, came down from 20 per cent to 17 per cent, which is a substantial drop of 3 percentage points within a year. This reflects a reduction in sustainable long-term employment during the period.

While there were shifts in the nature of work among males as well, they were less drastic, except for the fact that the share of regular-salaried workers among males also went down from 24 per cent in 2019-20 to 22.7 per cent in 2020-21.

Figure 2: Distribution of women workers across type of employment (in percentage points):

2019-20 vs. 2020-21

A look also at employment distribution across industries is informative. There was a slight decline in those engaged in the services sector, and a corresponding increase in agriculture and the manufacturing sector. For instance, women engaged in the service sector declined from 23.4 per cent in 2019-20 to 21.5 per cent in 2020-21.

In the case of male workers, while there was a slight decline in the share of senior officials and professions, the overall occupational distribution for males did not change much. In contrast, among working women the proportion of ‘Legislators, senior officials and managers’ came down from 5.8 per cent to 5 per cent, and ‘Professionals’ declined from 4.2 per cent to 3.8 per cent. This indicates a decline in formal jobs with social security provisions. On the other hand, the share of ‘Skilled agricultural and fishery workers’ among women increased considerably from 41.3 per cent to 44.9 per cent.

For workers engaged in the non-agriculture sector, the proportion employed in informal sector enterprises (comprising unincorporated enterprises owned by households i.e. proprietary and partnership enterprises including the informal producers’ cooperatives) increased from 69.5 per cent to 71.4 per cent as a whole. This shift was slightly more pronounced for males than for females in both rural and urban areas.

Thus, while overall labour market indicators during 2020-21 do not paint a dismal picture compared to 2019-20, higher work participation seems to be the result of distress employment. Even though we will have to wait for another year to access official employment data for 2021-22 from PLFS, the recent monthly data available from CMIE has already indicated that the situation has taken a downturn again between July 2021 and now.

As per CMIE, there has been a massive fall in total employment of around 13 million in June 2022 compared to May 2022, leading to the overall size of employment touching one of the lowest during the last one year. This is primarily because of a decline in rural agricultural labourers on the back of a sluggish monsoon, followed by a loss of salaried jobs. This is a clear indication of the temporary nature of employment gain in 2020-21 and a continuation of the uncertainties of India’s highly informal labour market.

Mridusmita Bordoloi is an Associate Fellow at Accountability Initiative.

Also Read: Social Protection to Safeguard Citizens against Vulnerabilities