Inside Delhi’s Doorstep Public Services Delivery Scheme

11 December 2019

My blog published earlier this year discussed brokers and their role in the delivery of public services. The Government of NCT Delhi (GNCTD) in 2018 launched a programme where they formalised these informal public service providers through an external agency. While 40 services were covered in September 2018, this was soon increased to 70 (across 12 departments) by July 2019, and a scale up to 100 is expected by this year. I take a look at the working of the doorstep delivery of public services project.

As part of the project, citizens can call ‘1076’ and book an appointment with a mobile sahayak. The mobile sahayak visits the service seekers’ residence at the given time and collects all requisite documents for the service, submits these documents with the concerned department in exchange of Rs 50 as facilitation fees. The sahayak then collects the final certificate from the government department, and delivers it back to the citizen to complete the transaction.

The services in this project include provision of certificates from the revenue department, driving licences and related services from the transport department, and availing access to certain social sector schemes. Most of these services are in high demand, and it can take days for service seekers to apply for and obtain important documents that can be essential to get benefits from government welfare schemes.

As per an annual report card, the GNCTD claims to have been able to service approximately 99.5 per cent of the 2,00,000 requests booked. As many as 13 lakh calls (1.3 mn) were made by the public. The facility currently operates with more than 125 mobile sahayaks (facilitators), 100 call centre executives, 11 supervisors, 35 dealing assistants and 25 coordinators[1].

The institutionalisation of informal broker practices does incentivise assistance to the general public, however, there still are some teething issues observed through a year of the project’s operations.

- Technical readiness: The launch of the scheme was accompanied by a series of glitches in the system due to fluctuating demand and the backend team modified the software multiple times. The mobile sahayaks and the call centres were also initially working in silos, and delivery of services reportedly suffered due to lack of coordination.

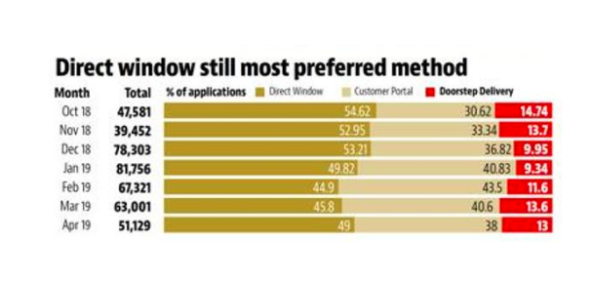

- Traditional methods are still more popular: While the scheme was primarily launched to minimise the complexity of Government to Citizen (G2C) services from multiple departments through intermediaries, it was seen that more than 50 per cent of applications were still made directly at the window.

- Rationalising resources: The scheme also faced issues with respect to planning its human resource base as most sahayaks initially quit their jobs due to less pay, and it was difficult to replace them. Among the requirements was for sahayaks to have their own two-wheeler for conveyance, which is difficult to fulfill.

- Understanding scale: Even as 1.3 million calls were made to the toll-free number, only 2,00,000 requests were booked and 1,50,000 were successfully resolved. While the churn rate of successful completion was high, it appears that the scale and demand of services was underestimated resulting in only 15% cases being booked out of the total calls received.

Source: Hindustan Times, 16 July 2019

All the challenges have important lessons. Donald F Kettl, a scholar of government and administrative reforms, has suggested that New Public Management (NPM) (such as the doorstep delivery of public services project) aims to “remedy a pathology of traditional bureaucracy that is hierarchically structured and authoritatively driven”. The accommodation of the role that brokers have played in service delivery in this case can be considered as a good example of NPM techniques. The government has attempted to eliminate rent-seeking, and create a leaner, incentive driven local administration.

Ketll suggests that the six key characteristics of the NPM approach are: productivity, marketisation, service orientation, decentralisation, policy oriented and being accountable by design. NPM clearly articulates a result-oriented relationship, specifying performance in a clear manner. This scheme was understood to be one-of-a-kind offering in India. While I would acknowledge it to be a constructive innovation by the GNCTD, the lack of technical capacity, public readiness and average resource allocation makes it less likely that the project will become a norm.

Any government service, when offered to the public, largely aims to ease public life or welfare, taking into account some degree of compatibility for uptake and reception by its beneficiaries. For a megacity like New Delhi, strong migration patterns, ad hoc living conditions for many, and the comfort associated with informal systems of access to public service delivery can become additional challenges.

_________________________

[1]‘Delhi Government delivered on 99.5% of doorstep service requests,’ Hindustan Times, 10 September 2019. Access it here.