Of Authorisation Letters, Samosas and Chai

1 January 1970

This is the second blog of a five-part series to unpack the meaning of some of the frequently heard terms and phrases in the Indian bureaucracy.

Oxford definition:

Authority: (1) The power or right to give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience. (2) A person or organisation having political or administrative power and control.

Authorisation: A document giving official permission

Bureaucratic translation:

The position or a document attesting your rank and status in the babu-dom (the world of the bureaucrat)

I first understood the clout of these powerful terms as I walked into the bureaucratic setup, the arena of ‘departments, circulars, orders, notices, and rules’. The complicated task of trying to gain access into this fortress-like organisation appeared formidable at first to me, especially since I was an ‘outsider’ – a freshly minted researcher just beginning to understand this field.

Surprisingly though, far from being treated like an outcast as I had feared, I quickly realised that there was something much more influential at work here. The magical power that ‘authorisation’ has to transform attitudes in this world would put even the best of Rowling’s potions and Potter’s charms to shame.

The behavioural transformation of the bureaucrat, as a consequence of knowing that you possess the much treasured authorisation letter, is almost instantaneous. It is marked usually by a change in tenor from the particularly repulsive (reserved especially for annoying salesmen who disturb a Sunday afternoon siesta), to that which embodies the Atithi Devo Bhava (guest is our God) level deference.

In one such instance, walking into a District Mines Office in Chhattisgarh, I remember having to wait for the longest time as an invisible entity in an official’s room, while he was busy engaging in an enlightening rant about the sorry state of Indian morality and ‘girls-these-days’ with his junior staff. Presumably, I was seen as one of the girls he was referring to (at least the looks of pity I was receiving seemed to suggest so). However this lasted only till I was able to quietly place a letter of authorisation from the Joint Secretary on his table requesting him to assist us in our project. In a matter of seconds, before one could even finish uttering the words ‘ji, sir-ji’ (Yes, sir), the Diwan-e-aam (the gathering of commoners) was dismissed, the paan-chewing stopped, and I was offered a chair to, ‘please make yourself comfortable, madam’.

In another scenario, the reaction was even more priceless. A government school principal who we intended to interview initially decided to not show up, and instead sent his clerk to let us know that ‘saheb abhi busy hain, baad mein aana’ (Sir is busy, come later). Another teacher, likely sent by the man himself, came to inquire, ‘Kahan se aaye hain aap? Koi authorisation hai kya?’ (Where have you come from? Do you have any authorization?). The clarification that our study had the requisite permissions from the concerned department resulted in an immediate invitation to what is usually reserved only for the ‘very special’ in such cases – chai and biskut (tea and biscuit). In fact we were privileged enough to be granted the ultimate honor of samosas and mithai (snacks and sweets) as well – ‘local speciality, madam, taste toh kijiye! (It is local speciality madam, you must try it!)’, while we waited for the principal who rushed to meet us. It is my studied observation that in such cases, the lavishness of the spread is almost always directly proportional to the perceived bade babu-ness (position in the bureaucratic order) of the issuing authority.

In light of instances like these, how does one even begin to make sense of the complex, love-hate relationship that the bureaucracy has with authority? Authority for the bureaucrat is that necessary evil, which, despite being the most reviled by him, is what ultimately molds his own behavior, constituting his official character.

What the bureaucrat hates most in authority (the enforced obedience and the necessity of compliance) is also precisely what he himself uses and revels in while dealing with subordinates and janta janardhan (them commoners). Perhaps this explains the grudging but absolute acceptance of authority one witnesses while engaging with the bureaucracy?

Curiously enough though, this does not imply that the mere presence of authority is sufficient to drive the bureaucrat into action. While on one hand, the need for requisite authorisation becomes an excuse to put tasks off or shirk responsibility; on the other hand, the rigidity of the system works at times against itself, disallowing even committed individuals from performing their tasks effectively.

As Max Weber, the grandfather of literature on the subject said, “The rational-legal authority underpinning bureaucracy derives its legitimacy from legal orders, which ultimately form an ‘iron cage’ of rules and laws that trap the very individuals that are a part of it.”

I remember vividly of the resigned helplessness with which a senior district official discussed the case of a young boy whose father’s name had been misspelt on his school leaving certificate due to a typographical error. Carrying a plethora of unusable identification documents, with folded hands, the mother of the boy stood in the office of the district office with her child, requesting him to approve the scholarship grants that the student had been denied as a result of the situation. With the father having passed away a few months ago, there was no way to establish the identity of the boy without going through a gamut of legal jargon and bureaucratic red tape. Unfortunately however, there was not much that the official could do, as the correction was outside his authority.

While discussing how such trivial things sometimes hold up work unnecessarily in the bureaucracy, he claimed ultimately that the fear of repercussions (being hauled up for questioning by seniors; having a red mark on their permanent record; salary cuts, or possible suspension orders issued against them for deviating from norms) holds most officials back even when they genuinely wish to help.

Good intentions are great, but ‘rules’ reign supreme. ‘Majboori hai madam, kya karein jab niyam hi aisa hai’ (We are bound, madam, what can we do when the rule is such) is an oft heard refrain that makes one pause and wonder on the usefulness of a system that ends up disrupting its own efficiency with its insistence on respecting authority and instructions.

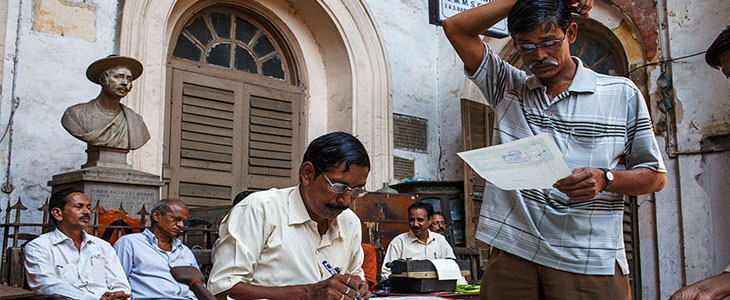

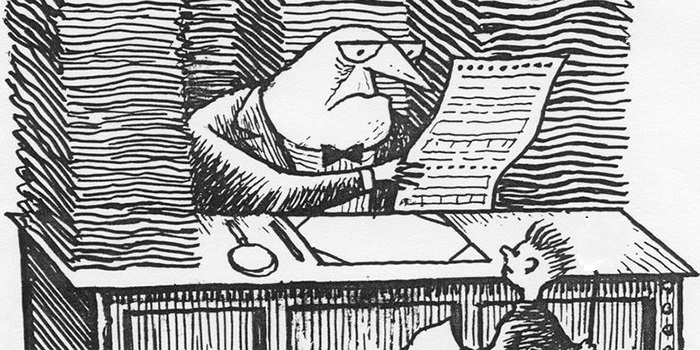

Lack of resources – both financial and personnel related – is another very real issue that holds back basic service delivery. Across departments and states one is frequently met with sights of mid and lower level government officials buried under reams of paperwork in their offices. The initial snappiness and curt reactions usually melt away when one gives a patient ear to the never-ending woes of chronic understaffing in the administration – Baaki sab toh theek hai madam, policy badhiya hai, par log kahan hain? (That is all well and good madam, the policy is great, but where are the people?)

In the next blog, we will discuss the matter of “babu ki kami” (shortage of clerical staff) in greater detail. Stay tuned!

Taanya Kapoor is part of the Public Administration team at Accountability Initiative. Her primary focus is on qualitative research to understand education reforms at the state level.