So far we have seen that Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) has been successful in increasing institutional deliveries. The scheme is performing well even in some of the most backward districts in the country. But there is a scope for improvement in its functioning especially with regards to delays in receiving benefits, payment of bribes and other problems in receiving the benefits.

This part of the series discusses the role of the Accredited Social Health Workers (ASHA) and the Auxiliary Nurse Mid-wife (ANM).

Part III- Role of ASHA & ANM

An ASHA is a critical element of the NRHM and JSY. As per the guidelines, an ASHA is supposed to identify pregnant women in the village, make sure that they receive antenatal care, identify a functioning government or accredited private medical facility where these women can deliver their baby, escort them and stay with them at the medical facility till the time of discharge. She is also supposed to arrange immunization for the newborn and postnatal care.

We covered only a few of these aspects in our questionnaire. The results are discussed below and indicated in a table at the end of the blog.

1. Mode of Transport and Transport Arrangements

65% of women delivering in government medical facilities reached the institution using car/ taxi/ jeep, while 6% used an ambulance. Making transport arrangement for pregnant women is an ASHA’s responsibility. But 82% respondents reported that members of their household or other relatives made travel arrangement. Only 16% women mentioned that such an arrangement was made by an ASHA, while 2% reported that some health worker, other than ASHA, made the arrangement. There are variations across districts- ASHAs in Sundargarh, Nalanda, Hardoi and Gumla perform better than ASHAs in other districts.

2. Staying with Pregnant Woman

Only 72% women delivering in government medical facilities reported that a health worker (either ASHA or ANM or Anganwadi worker) stayed with them during delivery. The proportion is highest in Sundargarh, Hardoi (more than 90% in both) and Gumla (88%), while it is lowest in Udaipur (48%) and Rajgarh (55%).

Only 67% of these women reported that the ASHAs stayed with them at the facility during birth. The proportion is highest in Sundargarh (96%) and Hardoi (82%), and lowest in Udaipur (30%), Rajgarh (35%) and Bhilwara (37%).

More worryingly, 18% of women delivering in medical facilities reported that none amongst ASHA, ANM or Anganwadi worker stayed with them.

3. Post Delivery Visit

An ASHA is supposed to visit the women within seven days of delivery to track their health post-delivery. But only 47% women reported of a health worker visiting them in a week. Out of these women, 60% reported that an ASHA visited them, while 25% reported being visited by an ANM. Thus, proportion of women who delivered at a government facility and reported that ASHAs visited them within seven days is barely 28%[1].

This discussion clearly indicates that the performance of ASHAs leaves a lot to be desired.

We also canvassed a short questionnaire separately for ASHAs, where we asked about timing of their appointment, amount they receive per delivery, days post-delivery to receive their incentives, and impediments (if any) in receiving these incentives.

The data indicates that three-quarters of the ASHAs interviewed were appointed in the period 2005 to 2008. Thus, lack of experience is unlikely to explain why ASHAs might not be able to perform as per expectations.

ASHAs receive Rs. 448 per delivery, on an average[2]. Interestingly, 35% of the ASHAs interviewed report receiving Rs. 350 per delivery, while 37% report receiving Rs. 600. Overall, 62% received less than Rs. 600 per delivery. ASHAs in Hardoi and Nalanda report receiving Rs. 600 per delivery, while ASHAs in Rajgarh and Korba receive the least amount per delivery within our sample districts, around Rs. 340 on an average. This might also reflect the fact that the households are making transport arrangements themselves and ASHAs are being paid only the incentive amount and amount for escorting women to the facility.

When it comes to the timing of receiving incentives post-delivery, overall, 58% of surveyed ASHAs received their incentives within or up to 7 days, while 65% received it within or up to 15 days[3]. Bhilwara, Sundargarh and Udaipur perform quite well. More than 80% of ASHAs in these districts receive incentives within 7 days. Hardoi and Gumla are the worst performers where only 17% and 28% ASHAs report receiving their incentives within 7 days post-delivery.

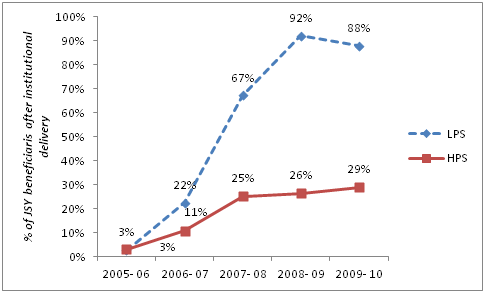

Our findings are consistent with those of other studies[4]. The CES (2009) for instance found that on average ASHA’s accompanied only 54.3 percent of women who delivered in government institutions in low performing States (LPS) and in only 49.1 percent cases, the ASHA stayed with the woman. Even in terms of motivation, the percentage of rural women motivated by ASHAs was 19.2 percent in rural areas. Interestingly, according to the NHRC survey, when JSY beneficiaries were asked why the ASHA had not accompanied them, in about “40% the reason was that institutional delivery was not promoted by ASHAs”.

It is clear from the above discussion that while the payment of the incentive to the individual beneficiary has resulted in an increase in institutional delivery, there are some gaps with respect to the role of the ASHAs, and we need more specific evidence to learn more about them.

In the next and the final section, we will summarize the main findings of the survey and look at some of the constraints from the supply side – in terms of public health institutions and their facilities.

| Rajasthan | Jharkhand | Uttar

Pradesh |

Chhattisgarh | Bihar | Madhya

Pradesh |

Orissa | Overall | |||

| Udaipur | Bhilwara | Gumla | Hardoi | Korba | Nalanda | Rajgarh | Sundargarh | |||

| Mode of transport to

government medical facility

|

Ambulance | 3.15 | 1.9 | 4.38 | 0.61 | 0 | 2.35 | 6.14 | 27.98 | 6.3 |

| Car/Taxi/Jeep | 79.13 | 86.08 | 58.13 | 58.18 | 47.19 | 60.09 | 56.68 | 65.8 | 64.94 | |

| Who made arrangements

in case of car/taxi/jeep to the government facility?

|

ASHA | 7.96 | 13.24 | 23.91 | 23.96 | 0 | 28.13 | 3.25 | 29.13 | 16.09 |

| Other health

worker |

2.99 | 4.41 | 1.09 | 0 | 7.14 | 0 | 0.65 | 0 | 1.74 | |

| Household | 86.07 | 77.94 | 72.83 | 75 | 88.1 | 69.53 | 90.26 | 67.72 | 78.79 | |

| Other relatives | 1.99 | 2.94 | 2.17 | 0 | 4.76 | 2.34 | 5.19 | 3.15 | 2.77 | |

| Did any health worker stay with you at

the govt. facility during the birth? |

47.68 | 58.11 | 87.66 | 90.8 | 76.19 | 80.86 | 54.62 | 96.95 | 72.18 | |

| If yes, who stayed with you at the government facility?

|

ASHA | 29.73 | 37.21 | 78.46 | 81.63 | 54.69 | 79.75 | 34.62 | 96.28 | 66.54 |

| ANM | 26.13 | 23.26 | 11.54 | 3.4 | 14.06 | 7.36 | 7.69 | 2.66 | 10.3 | |

| AWW | 7.21 | 15.12 | 4.62 | 2.04 | 10.94 | 1.23 | 12.31 | 0 | 5.4 | |

| None | 36.94 | 24.42 | 5.38 | 12.93 | 20.31 | 11.66 | 45.38 | 1.06 | 17.76 | |

| Did any health worker visit you at the govt. facility during the birth? | 41.67 | 42.04 | 72.26 | 41.36 | 53.93 | 54.07 | 19.03 | 72.02 | 47.21 | |

| If yes, who visited you? | ASHA | 23.53 | 40.63 | 67.27 | 75.76 | 51.06 | 78.18 | 20 | 84.56 | 59.71 |

| ANM | 42.16 | 32.81 | 26.36 | 10.61 | 25.53 | 15.45 | 66 | 6.62 | 24.96 | |

| AWW | 24.51 | 23.44 | 4.55 | 6.06 | 21.28 | 3.64 | 2 | 4.41 | 10.22 | |

| Others | 7.84 | 3.13 | 0.91 | 7.58 | 0 | 1.82 | 10 | 2.94 | 3.94 | |

| Don’t know | 1.96 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 2.13 | 0.91 | 2 | 1.47 | 1.17 | |

| Amount received by ASHA per delivery (Rs.) | Mean | 354.84 | 426.92 | 395.87 | 596.51 | 342.39 | 600 | 340.38 | 477.38 | 447.61 |

| Median | 400 | 400 | 350 | 600 | 350 | 600 | 350 | 550 | 400 | |

| Observations | 31 | 26 | 49 | 43 | 46 | 38 | 26 | 42 | 301 | |

| % of ASHAs receiving incentives after delivery in government facility | Within 7 days | 83.33 | 87.1 | 27.91 | 16.67 | 63.04 | 48.72 | 59.26 | 86.36 | 57.79 |

| Within 14 days | 86.11 | 90.32 | 30.23 | 33.33 | 73.91 | 51.28 | 77.78 | 88.64 | 64.94 | |

| Days post delivery to receive the amount | Mean | 8.06 | 7.16 | 28.74 | 23.48 | 8.52 | 24.03 | 7.56 | 4.86 | 14.55 |

| Median | 3 | 3 | 30 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 5.5 | |

[1] (47% * 60% = 28%)

[2] Median is Rs. 400. There are 3 observations with values above Rs. 100 and 3 observations with values greater than Rs. 800. These have been excluded in calculations.

[3] 15 observations with more than 90 days have been excluded in these calculations.

[4] Coverage Evaluation Survey (2009), NHRC(2010), UNFPA (2007)