This year in May, a nine-year old in Scotland started blogging[1] about the quality of meals in her school, complete with a picture, a ‘food-o-meter’, that rated the meal on a scale of 1 to 10 and the number of pieces of hair in her food. When Martha Payne’s blog became popular, the local council panicked and banned her blog, fearing that the reports could get the catering staff fired. The Council’s reaction only increased Martha’s popularity. The media had a field day, celebrity chefs such as Jamie Oliver decided to intervene and the council had to retract the ban. As a result of the attention to her blog, Martha reports that the meals taste better and the portions are larger. Martha’s story offers a lesson that the Midday Meal (MDM) Scheme, the world’s largest school feeding programme can learn from: the need to place the key beneficiary, the child, in the centre of the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) process.

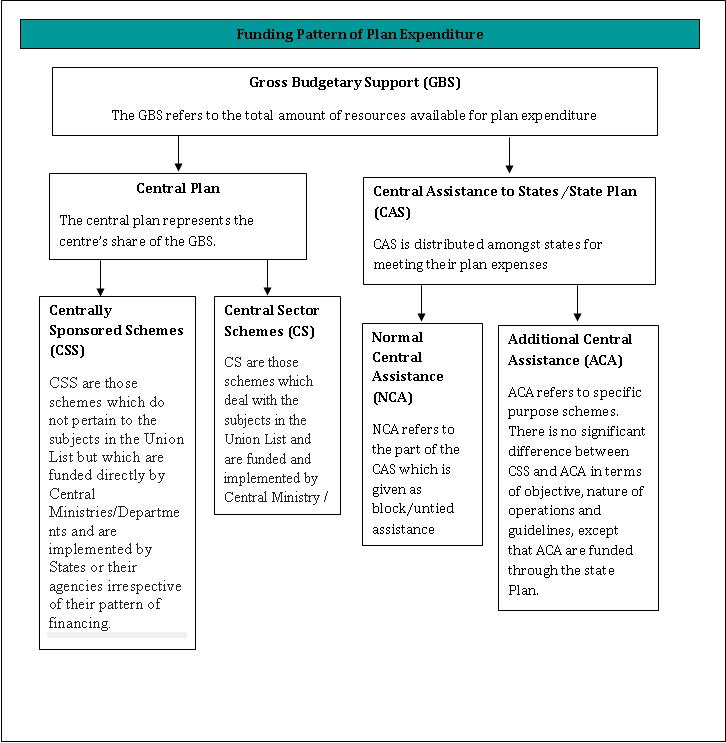

Launched as a centrally sponsored scheme in August 1995, MDM aims to improve enrolment and retention in (government and aided) schools, and the nutrition levels of children availing the scheme. MDM allocations stand at 31% of the total elementary education budget[2]. Over time, states have also adopted innovative MDM practices to increase the efficiency of the implementation of the scheme by involving children’s mothers, through Mahila Samakhyas (Bihar), Saraswati Vahinis (Jharkhand) and Bhojan Mata (Uttarakhand), in cooking and serving the food in schools[3].

Bihar and Jharkhand have involved children to a modest degree where Bal Sansads (Child Cabinets) oversee the distribution of MDM, check if children have washed their hands and cooks have worn their aprons. The MDM, counter-intuitively, does not have child representatives in the M&E process. Take Bihar, as an example. At present, Bihar has 6 bodies to monitor the scheme at the state, district, block and school level.

| Bihar’s MDM Monitoring and Evaluation Structure[4],[5] | ||

| No. | Individual / Group | Task |

| 1 | State Steering cum Monitoring Committee | At the District level there is a Nodal Officer – the District Magistrate and a District Resource Person (DRP) to monitor the scheme. Each DRP monitors 50-100 schools a month. |

| At the Block level, the scheme is monitored by Block Resource Person (BRP). Each BRP monitors 50-100 schools a month. | ||

| 2 | Bihar Rajya Madhyanha Bhojan Yojana Samiti’s Mid-Day Meal Cells

|

At the State level, the MDM Cell has a Director with a State Programme Coordinator, one Database Administrator, four Assistant Programme-Coordinators to assist him as well as a team of two Junior Monitoring Officers, four Assistants, one Account Officer and two Accountants to monitor and supervise the programme. |

| At district level, the cell has a District MDM In-charge (A senior Deputy Collector from the Bihar Administrative service) who is assisted by one District Coordinator, one Accountant-cum-Computer Operator and two Resource Persons to monitor and supervise the programme. The District MDM is in charge of checking if MDM has been prepared in all the schools, the quality of the food, if all schools have funds and food grains and the grievance redress mechanism. | ||

| At the block level the cell has one resource person to monitor and supervise the programme. | ||

|

Additionally officers have been contracted – two resource persons at the District level and one at the Block level to provide regular monitoring and support |

||

| 3 | School Management Committee | At the Block level, the Block Education Extension Officer holds a meeting with the Block Resource Person and members of SMC to monitor the utilisation of the MDM funds. |

| 4 | Monitoring Institutions[6] | Bihar has two External Monitoring Institutions,

Jamia Millia, Delhi and A.N. Sinha Institute of Social Studies, that monitor the regularity of delivering grains, cooking funds and serving meals. Also, they monitor the quality and quantity of meals and whether children were discriminated against during MDM, as well as the adequacy of cooking infrastructure. |

| 5 | Gram Panchayat/PRI members | Provide monitoring support when required. |

| 6 | Online Monitoring System – mdmsbihar.org.in |

BRPs and a Sub Divisional Education Officer (SDEO) send SMS reports to an online portal. Their tasks overlap with those of DRP and BRP of the Steering and Monitoring Committees. |

Despite the complex monitoring and evaluation structure, cases of poor quality meals come to light only when there are glaring discrepancies, for example 60 children falling ill in West Bengal in July[7] or the alleged murder of a Standard Eight student for leading the protest against the poor quality of MDM in his school earlier this month, also in West Bengal[8].

While setting up blogs for all the recipients of the MDM – Martha Payne style – may not be feasible (yet) in India, a step towards involving the child directly in evaluating their meals can be made possible in the present M&E structure, through the Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS). Currently introduced in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the IVRS records teachers responses at the end of the meal every day, and makes this data available to the public real-time. The same process can be used to record children’s responses about the availability, quality and quantity of the meal served to them, instead of restricting the role of evaluator and monitor to adult members of school staff and management committee, and government officers. The impact of IVRS has yet to be assessed and there is a need to be cautious about the ability of technology to seamlessly integrate the student in the M&E process (verifying the authenticity of the recipient/data entered). However, the process can change the role the child from a passive participator in the M&E process, to a more active respondent. It can be an attempt to create a direct link between the planners and the recipient.

[1] http://neverseconds.blogspot.in/

[2] http://www.accountabilityindia.in/sites/default/files/mid-day_meal_scheme_2012-13.pdf

[4] http://mdm.nic.in/Files/PAB/PAB2012-13/Bihar/1_AWPB_Wtite_up_2012-13.pdf

[5] http://mdm.nic.in/Files/Review/Reports/2010/Bihar%20RM%20report%20final-2010.pdf

[6] http://mdm.nic.in/Files/MI%20REports/Monitoring%20Institution%20list.pdf

[7] http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-06-20/india/32335302_1_mid-day-meal-tribal-students-primary-school

[8] http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/boy-killed-for-protesting-poor-quality-mid-day-meal-in-west-bengal/1/203772.html