The PAISA survey is conducted annually through the Annual Survey of Education (ASER) –Rural. This is the second PAISA report. In 2009, the survey covered a total of 14231 government Primary and Upper Primary Schools in rural India. The 2010 survey covers 13021 government primary and upper primary schools across rural India. The ASER survey is conducted through civil society partners. PAISA is the first and only national level, citizen led, effort to track public expenditures.

PAISA’s specific point of investigation is the school grants in Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA). SSA is currently the Government of India’s primary vehicle for implementing the Right to Education Act in India. SSA is thus the most crucial vehicle for the overall provision of elementary education in the country today. In FY 2009-10, total SSA allocation for the country (including state share) was Rs. 27, 876.29 crore. School grants accounted for Rs 1635.32 crore (about 6%) of this total allocation. Small as they are, these constitute as significant proportion of monies that actually reach school bank accounts and the only funds over which school management committees can exercise some control. Consequently, school grants have a significant bearing on the day to day functioning of the school – whether school infrastructure is maintained properly, administrative expenses are catered for and teaching materials (apart from textbooks) are available.

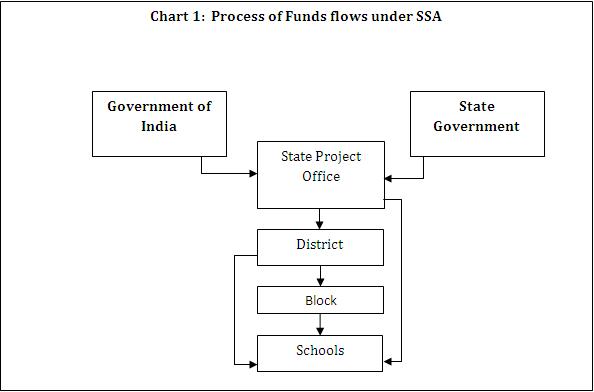

Over the last two years, three types of grants have been provided for all elementary schools in the country.[2] These are: a) Maintenance grant; (ii) Development grant or School grant; and (iii) Teaching Learning Material grant (these go directly to the teachers). The grants arrive at schools with very clear expenditure guidelines. The Maintenance grant is for infrastructure upkeep, the Development / School grant is meant for operation and administration, and Teacher Learning Material is meant for extra instructional aids that may be required for teaching. Apart from this, under the SSA framework, grants are also provided for building additional classrooms, but not all schools get this grant making it difficult to track. SSA grants are supplemented by other grants which are provided by the State governments for items such as school uniform, additional teaching-learning equipment like science or sports kits, extra books and study materials, and cycles for girls in upper primary schools. In the annual work plan and budget for SSA, each block, district and state provides the quantum of funds required for this purpose on the basis of need expressed and state and central guidelines, grants for activities not provided under the SSA fund are funded from the State government’s budget.

The PAISA survey focuses on the following key questions:

(a) Do schools get their money?

(b) When did schools get their money? i.e. did funds arrive on time?

(c) Did schools get their entire entitlement – the set of grants that are meant to arrive in school bank accounts as per the norms?

(d) Do schools spend their money?

(e) If so, what are the outputs of this expenditure?

This year, we added two new elements to PAISA. First, we tried to map school level expenditures with activities at the school level. We narrowed the activity list to the specific activities that schools can undertake through the larger two of the three grants they get – School Maintenance and Development/School Grant. The effort behind this was to try and assess the quality of expenditures by using the specific activities that schools spend their money on as a proxy for planning efficiency (the extent to which plans match with school needs) and the extent to which funds available are sufficient for school needs.

The second new addition is the RTE. ASER 2010 has created the first ever citizens benchmark of compliance with RTE norms. Using this data, PAISA has tried to arrive at a rough cost estimate to assess how much money it would take for the Government of India and State Governments to ensure that schools meet RTE requirements. This, it is hoped will be the beginnings of a citizen led assessment of government compliance with RTE norms.

Findings from PAISA Survey: India Rural

1) Do schools get their money? In 2009-10, over 80% primary and upper primary schools reported receiving the three mandatory grants. There are some differences across the type of grants. In primary schools, 83% and 86% reported receiving Maintenance (SMG) and Teacher Learning Material (TLM) grants while a marginally smaller 78% reported receipt of Development/School Grant (SG). A similar pattern is found in upper primary schools where 88% and 90% reported receiving SMG and TLM while 85% received SG. The 2009-10 results show a marginal improvement of 7 percentage points from 2008-09 for primary schools and upper primary schools (averaging across grants for each school type).

2) Does money reach on time? To assess the efficiency and timeliness of fund flows, schools were asked whether they received grants for the current fiscal (FY 2010-11 in this case) at the time of the survey. The survey is conducted between October and November which is half way through the financial year. On average about 54% primary and close to 68% upper primary schools reported receiving grants half way through the financial year. While the differences across types of grants are marginal, the difference between primary and upper primary schools is significant and merits further investigation. Here too, there is a difference between fund flows in 2009-10 and 2010-11 of 3 percentage points for primary schools and 10 percentage points for upper primary schools (averaging across grants for each school type).

3) Do schools get all their money? While schools get money, data suggests that they don’t always report receiving their entire entitlement (in terms of number of grants). It is important to note that on close examination of the data, there were cases where respondents did not indicate type of grants and instead reported receipt of one consolidated figure. Therefore, this data could also be taken as a proxy for awareness levels amongst Head Teachers (the primary respondents of this survey). In FY 2009-10 68% primary schools reported receipt of all three grants compared with 54% in 2008-09. 70% upper primary schools reported receiving all three grants up from 60% in 2008-09.

Unsurprisingly, the half year results paint a depressing picture. In 2010-11 44% primary schools reported receiving all three grants. Given that about half the schools reported receiving grants this could mean that the general pattern is that grants arrive in bulk and schools either receive all their grants at one time or nothing. Upper primary grants tell a similar story – 56% upper primary schools reporting receipt of all three grants. Again this is a significant improvement from 2009-10 results.

4) Do schools spend their money? On average about 90% schools that receive money report spending their money. This is the good news. The bad news is that delays in receipt of funds seriously compromise the quality of expenditures. First late arrival of funds means that time bound expenditures such as pre-monsoon repairs, purchases of basic supplies in schools cannot be undertaken at the time of need. Second, late arrival of funds means that schools have to rush to spend their money which inevitably leads to poor quality expenditure.

5) What are the outputs of expenditures: what activities do schools undertake with their funds? The first step to assessing the outputs is to determine the precise activities that schools report spending their money on. To do this in PAISA 2010, we developed a list of activities that schools are entitled to undertake using SMG and SG funds. These can be broadly classified in to three types: a) essential supplies – such as purchasing registers, pens, chalks, dusters and so on, b) infrastructure – such as repair of the building, roof, playground and c) amenities – such as white washing, maintaining and repairing toilets and hand-pump amongst others. The PAISA 2010 survey found that by and large all schools (about 90%) use their funds to purchase supplies- both classroom and other supplies. White washing walls is also a popular activity with 64% primary and 72% upper primary schools reporting undertaking white washing activities in the last year. Next comes building repair at 52% for primary and 61% for upper primary schools. Clearly, most schools prioritize activities that are necessary for the day to day functioning of the school. Given that relatively few other activities are undertaken and that most of the money that arrives at schools is spent, one possibility is that this emphasis on essentials over infrastructure and amenities is a factor of insufficient funds – given the small quantum of money that actually arrives at schools it is possible that much of the money is absorbed in undertaking these necessary purchases. When it comes to non-essential activities, white washing seems to be a popular activity with all schools. This could be a factor of weak planning and that expenditures are not necessarily linked with school needs. The data suggests that approximately 70% schools white wash their schools but in reality, it is unlikely that such a large proportion of schools needed to white wash their walls over other activities in a given year or that white washing is more important than say repairing a roof or maintaining toilet and drinking water facilities. Anecdotal evidence suggests that one reason for this emphasis on white washing is that it is an easy tangible activity to undertake if funds have to be spent quickly and this is perhaps the reason that schools use the money they have left over from supply purchase for white washing their walls.

Interestingly, very few schools undertook repair and maintenance work on toilet and hand pump facilities and as we shall see in the next section, these facilities are in need of prioritization.

6) What facilities do schools have? In 2010, 74% schools reported having drinking water facilities indicated by the presence of useable handpump/ taps. The remaining 26% include schools that a) did not have any drinking water facility; b) had handpumps/ tap but these were non functional, and c) schools which have drinking water facility other than handpump/tap, which typically means water stored in containers. Calculations indicate that the proportion of schools with unusable handpump/tap is actually marginally higher at 9.22% than the proportion of schools without any drinking water facility, 7.62%. Since the government statistics do not record the usability aspect of the handpump/tap, this important fact goes unnoticed. Thus, making sure that the handpump/tap is functional is as important as providing the schools with them in the first place. What is worrisome is that the current situation is not so different from the situation a year ago.

The picture is even worse as far as toilet facilities are considered. In 2010, 11% of the schools surveyed did not have any toilet facility (neither common, nor for girls or for boys). But, having a toilet doesn’t guarantee access. In 27% schools, the toilet facility was locked. In 10% schools, toilets were unusable. Thus, in total, barely half of the schools (53%) surveyed had a usable toilet. These numbers are somewhat an improvement over 2009, when less than half of the schools had any usable toilet facilities.

7) To what extent the schools comply RTE norms and what are the cost implications of the RTE compliance? The Right to Education (RTE) Act lays down certain human resource and physical infrastructure norms for every school in the country. Information about some of these is available in the survey. They include Pupil Teacher Ratio (PTR) in primary and upper primary schools (human infrastructure) and a) boundary wall/ fencing, b) safe and adequate drinking water, c) kitchen shed, d) library, e) playground, f) separate toilet facility for boys and girls- (physical infrastructure).

32% primary schools and 8% upper primary schools have fewer teachers than prescribed by the RTE. Only 11% government schools are in compliance with all the seven physical infrastructure norms prescribed by RTE for the country. India needs Rs. 15,158 crore if the all schools are to become RTE- compliant. Details of the costing exercise are given in a separate article in this volume.

8) How do states compare with one another? To examine this, we have ranked states as 5 best and 5 worst based on the number of schools that received all 3 grants in full and half financial years. Comparison over two years allows us to assess improvements or lack of aross states. Nagaland, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Maharashtra are the top 5 states (in no particular order) for the full financial year for both years. Interestingly, when it comes to timeliness (i.e. states that report grant receipt for all 3 grants at the time the survey is conducted), Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra fall off the list. In 2009-10, Goa and Gujarat found place in the top five on timeliness. In 2010-11, Goa was replaced by Punjab. Andhra Pradesh which was amongst the worst performers in timeliness in 2009-10 improved its grant flows in 2010-11 but doesn’t reach the top 5 mark.[3]

Now to the specifics, Nagaland tops the list for both years with a marginal improvement in 2009-10. In 2008-09, 85% and in 2009-10 88% schools in the state reported receiving all 3 grants. Nagaland also does very well on timeliness with 64% schools reporting grant receipt half way through the 2009-10 financial year. This improved significantly in 2010 with 84% schools reporting grant receipt half way through the year. Karnataka comes second in the list with 76% schools reporting receipt of all 3 grants in 2008-09. This improved to 87% in 2009-10. In the current fiscal (2010-11) Karnataka improved its grant speed with as many as 82% schools reporting grant receipt half way through the year compared with 53% half way through FY 2009-10. Himachal Pradesh dropped from third position in 2008-09 to fifth in 2009-10 owing to an overall improvement across states in grant flows. In 2008-09 70% schools reported receiving all three grants and this improved to 83% in 2009-10. On the half way mark, although the state improved its flow of funds from 55% schools receiving all 3 grants to 78%, Himachal dropped its overall position from 2nd to 3rd in 2009-10. Maharashtra improved its position from 5th in 2008-09 with 67% schools reporting receipt of all 3 grants to 4th position in 2009-10 with 85% schools reporting receipt of all 3 grants. Andhra Pradesh moved from 4th position at 69% in 2008-09 to 3rd position at 85% in 2009-10.

Meghalaya, is the worst performer both in 2008-09 and 2009-10 with an average of 23% schools reporting receiving all 3 grants in both years. Meghalaya also does poorly in terms of timeliness with a mere 2% schools reporting receipt of all 3 grants in 2009-10. This improved only somewhat to 10% in 20010-11. Rajasthan which was the 5th worst performer at 37% in 2008-09 improved its performance to 55% in 2009-10. In terms of timeliness, the state has shown some improvement over the last two years. In 2009-10 Rajasthan was the 5th worst performer at 12% this has improved to about 30% in 2010-11. Other poor performers for 2008-09 were Mizoram at 35%, Tripura at 34% and Manipur at 27%. In 2009-10, the worst performers were Arunachal Pradesh at 60%, Sikkim at 57%, Rajasthan at 55%, Tripura at 47% and Meghalaya at 24%.

[1] Yamini Aiyar is Director, Accountability Initiative, CPR. Ambrish Dongre is Senior Researcher, Accountability Initiative, CPR.

[2] With the implementation of RTE for the 2010-11 fiscal some states introduced new grants such as a transport grant and uniform grant. In the interests of developing a comparative picture both across years fiscal years and across states, we have restricted our tracking exercise to these 3 grants. In PAISA 2011, we will track these new grants.

[3] Important to note that we have removed Tamil Nadu from this comparison because Tamil Nadu does not report separately on the TLM grant. It also excludes Union Territories.