This interview was conducted as a part of a research study funded by the Azim Premji University under the COVID-19 Research Funding Programme 2020. The study delves into the experiences of frontline workers in Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It was conducted with an ASHA in Udaipur, Rajasthan on 13 January 2021 in Hindi, and has been translated.

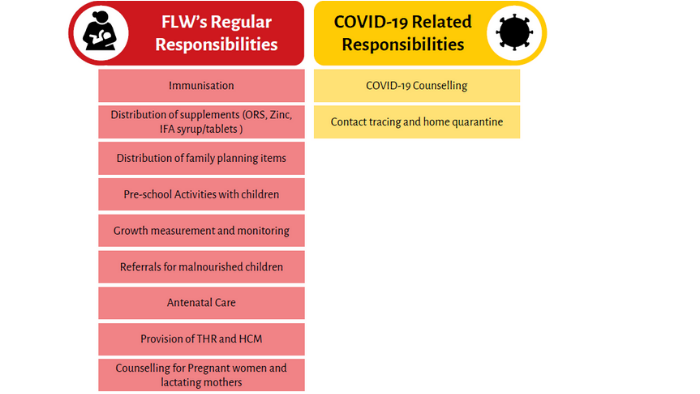

Q: During the past nine months, you have been involved with COVID-related work. Can you give a brief overview of what your COVID-19 pandemic and non-pandemic duties were?

ASHA: In terms of my pandemic-related tasks, the first and the most important one was to keep doing surveys. Whenever someone would enter the village, we would have to go to their place and get information on how many people they arrived with, what vehicle they arrived in, note down the vehicle number, and then ask them if they have any symptoms of cough and cold or if they had already been tested for the virus. This task kept us occupied through March-May.

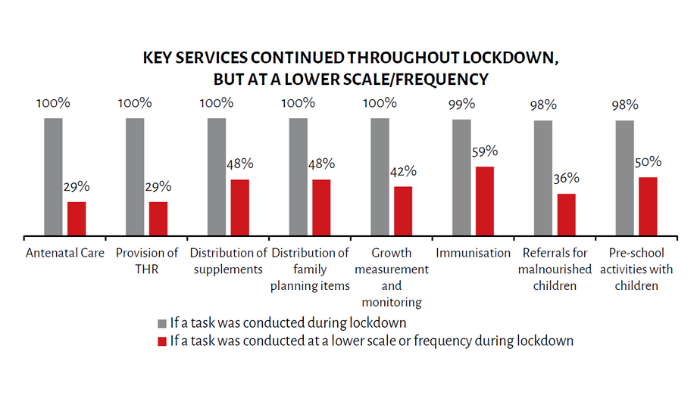

In May, we resumed our other tasks like weighing pregnant women, assisting with deliveries and conducting immunisations. It’s not like we didn’t do these tasks in the previous months, but we highly discouraged people from coming to the Primary Health Centre for these. Instead, we asked them to inform us beforehand if they required any of our non-COVID related services, and then we would go to their homes and help them with anything that they needed.

I am in-charge of my own village, and have a population of 900 under me, so it has not been that difficult to fulfill these tasks.

Q: What was your relationship with other Frontline Workers (ANMs, AWWs and ASHAs)/other Corona Warriors in your area post the pandemic? For instance, how often do you speak with each other, and what coordination have you been doing?

ASHA: My coordination was primarily with the ANMs. In fact, there is an ANM that I do all my pandemic and non-pandemic related work with. We even do our surveys together! This helps both of us as not only we have company while doing the work, but we also get emotional support.

Whenever there is any problem, instead of going to my supervisor, I would just ask my ANM didi because I feel much closer to her.

My supervisor though has been very supportive throughout.

Q: What has motivated you to come to work and carry out your activities during the pandemic?

ASHA: I have been in this job for over six years now, so it is more like second nature to me. I have always wanted to work in the field of health, it is like a dream come true for me! There is also some comfort in knowing that I am financially independent. I don’t make a lot of money from this job, but it’s good enough to make me feel that I don’t have to entirely depend on my husband for everything, so that has kept me motivated.

During the pandemic period, the biggest motivation is that I get the opportunity to give back to the society. I get to work for my own people and help them, and this has kept me motivated despite backlash from these people for doing my work.

Q: Have there been challenges to carrying out your work?

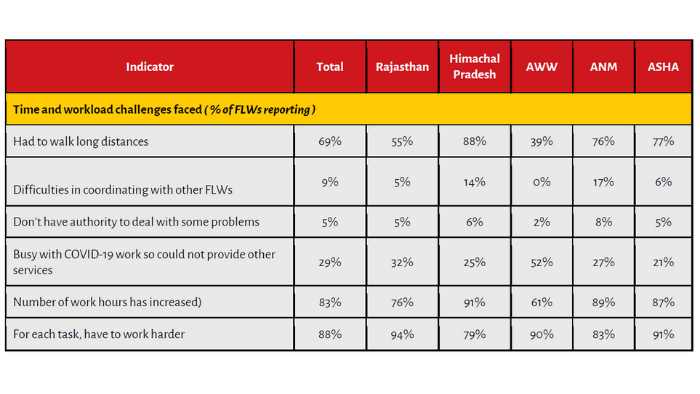

ASHA: My area is really large so, a lot of the times, I have to walk 3-4 kms every day, and that has been a big problem. It is very difficult to get transport because no one is ready to help Frontline Workers (FLWs). They all think that, because we are in the field all day, we are infected with COVID-19, and will also make them sick! We have tried everything, we even tell them that instead of giving Rs. 200 for a ride, we will give them Rs. 500, but even then they do not agree.

I have not got any reimbursements for all the extra money I have spent on travelling, and doing door-to-door surveys. I spend Rs. 50-70 everyday. I got my salary on time.

The people of this village are not ready to listen or cooperate. They do not like it when we go to their homes to do surveys. Most of the times they lash out at us saying that we should not come unannounced.

I remember, this one time, a patient was diabetic and had COVID-19 symptoms, but lied to us. Later, when she tested positive, she revealed that she had been showing symptoms for a while. Because of this the entire family got COVID-19!

There is a lot of stigma around this virus which prevents people from getting tested. Some of the people also told us that they will file police cases against us if we keep coming to their homes for surveys. I was doing surveys with my ANM didi and one of the households let the dogs out on us, and she got hurt. The people did this because they didn’t want to get tested for COVID, and were really frustrated with FLWs coming to their homes again and again for the same thing.

The timing of this job is also a big problem — I feel like I am always doing pandemic-related work. I have two small children at home but I don’t get the time to help them. I leave home at 6 AM and come back by 7 PM.

Q. How did you overcome challenges that you faced?

ASHA: The first thing that I always do is to talk to people. I try my best to impart knowledge about the facts that can help them be less scared of the disease, and be more open about the symptoms that they are facing. I also tell them that we don’t go around telling everyone about the people who have COVID-19. I tell them that there is utmost confidentiality so they shouldn’t feel ashamed.

To manage the problem of transport I usually ask my husband to help. Moreover, whenever a seat is denied to me in public transport, I show them my FLW ID card and tell them I will complain to the police.

Lastly, to cope with the burden of the job, I have learnt how to manage my time better. Earlier, it was very tough to give so many hours to this job but now I wake up early, do my household tasks beforehand, and by the time it’s 6 AM, I am ready for any work that my supervisor may allot me.