Understanding Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation, and its Limitations

25 March 2021

Why are many countries unable to accelerate their growth and development? This longstanding question, pivotal to the field of economics, continues to defy consensus. A recent diagnosis – offered by Matt Andrews, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock at Harvard University – says that developing countries have limited capacity for implementing policies effectively. Their solution is to create better procedures for policy development and execution through an approach called Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) [1] [2]. What is PDIA and how feasible is it in India?

The starting point of their thesis is that developing countries, such as India, face “capability traps”, characterised by an insufficient capacity for identifying causes for poor performance and enacting corrective measures. Countries face limitations in recognising the ‘what’ (what is the ‘ailment’?) as well as the ‘how’ (how to ‘treat’ it effectively?) of achieving socioeconomic welfare.

Consequently, policymakers often opt for the next-best solution – a ‘leap of faith’ in the adoption of best practices that have worked in other contexts (which they call “isomorphic mimicry”). However, this approach precludes the unique circumstances of developing countries, their challenges, and hence does not reap benefits, they say.

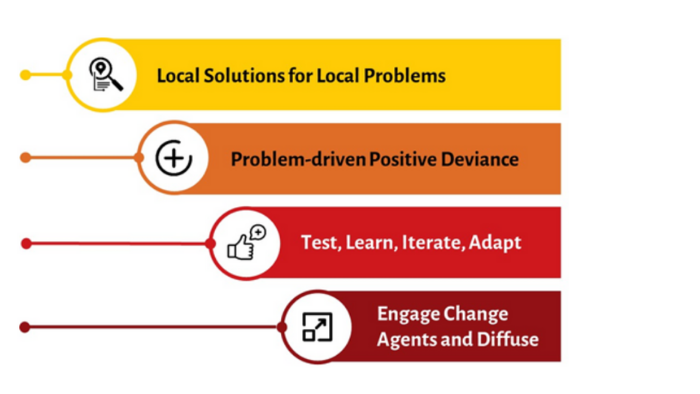

As per Andrews et al., the answer lies in improving the state’s own capacity for devising and implementing “locally relevant solutions to locally perceived problems”. They propose to achieve this through PDIA. The ingredients of the PDIA process (see Figure 1 below) are:

- Detect Problems Locally: Moving away from the application of a predetermined set of ‘best practices’ to the identification of local problems and possible solutions.

- Encourage Experimentation: Fostering an administrative environment that allows for testing locally-developed solutions and finding positive deviances.

- Feedback and Adaptation: Gathering evidence on the efficacy of potential solutions through experimentation, and adapting these in an iterative manner.

- Garner Support of Change Agents: Engaging a wide range of actors to ensure reforms can be practically implemented, and have political support.

In this manner, PDIA allows for key issues and resolutions to be recognised by local agents themselves, thereby augmenting their capacity for development.

Figure 1: Schematic Outline of Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) Source: Figure based on Andrews, M. et al. (2015)

Source: Figure based on Andrews, M. et al. (2015)

While this sounds promising, how feasible is PDIA in India? Policymaking in India has a centralised structure. Social sector schemes are determined by the Union and state governments, keeping in mind socioeconomic requirements and political motivations. In light of this, there are three potential roadblocks to PDIA in India: (i) the top-down structure of policymaking; (ii) ending up with asymmetric policy and implementation plans; and (iii) disincentives of failed experiments [3].

The above are not intended as criticisms of PDIA’s efficacy, but rather contextual limitations on how well it could be applied in a policymaking context, such as that in India. Let us explore these in turn.

First, PDIA is centred on ideas emerging from local change agents. In India, however, policy formulation is typically carried out by senior bureaucrats in the administrative setup. To put PDIA into action, decision-making authority would need to be transferred to local officials and frontline workers. In the current scheme of things, this may be met with scepticism on the ability of these functionaries to formulate and implement solutions – precisely what PDIA seeks to develop.

Second, the impediments to welfare outcomes are likely to differ across contexts. As per the PDIA approach, this would require mechanisms that solve local problems, leading to policies that differ across areas. Even though exceptions – such as the Gram Panchayat Development Plans (GPDPs) – exist, policymaking in India largely follows a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. Programme guidelines are largely created in a centralised manner, to be implemented more or less uniformly precluding contextual variations to a large extent – for instance, the manner in which Centrally Sponsored Schemes are designed and operationalised [4].

PDIA, on the other hand, would call for policy decisions to be taken at a more diffused level, with guidelines and budgetary requirements tailored to context.

Lastly, PDIA calls for iteratively arriving at policy responses by testing potential answers and learning from mistakes. Andrews et al. remark that we need to move towards “systems that tolerate (even encourage) failure as the necessary price of success”. It is self-evident that career progression of policymakers and administrators are connected with how well they perform their duties. This implies that there are disincentives with unsuccessful policy decisions at present; undoing this would require a monumental shift in the mechanisms of performance appraisal for the bureaucracy.

PDIA can only operate in an ecosystem that is more tolerant of experimentation and failure, one where policymakers are not discouraged from taking potential missteps, and disincentives from doing so are minimised.

PDIA has emerged as a new way of tackling persistent issues or ‘wicked problems’ which are seemingly complex and unsolvable (watch this video on government perception of citizen participation to understand more). Governments across countries looking to test it out (such as its application in the public financial management sector in Mozambique).

As highlighted in this blog, the success of PDIA in a country such as India will be constrained by the nature of the policymaking environment. Structural changes in how policymaking is carried out would be needed – with increased participation of officials and functionaries down the rung in policy decisions, recognition of local contexts, and changes to incentives associated with trial-and-error.

Notes:

[1] Andrews, M., Pritchett, L. & Woolcock, M. (2012). “Escaping Capability Traps through Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA)”. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP12-036, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Retrieved from URL: <https://www.cgdev.org/publication/escaping-capability-traps-through-problem-driven-iterative-adaptation-pdia-working-paper>

[2] Andrews, M. et al. (2015). “Building capability by delivering results: Putting Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) principles into practice”. In Whaites, A. et al. (2015). “A Governance Practitioner’s Notebook: Alternative Ideas and Approaches”. OECD, Paris. Retrieved from URL: <https://www.oecd.org/dac/accountable-effective-institutions/Governance%20Notebook.pdf>

[3] Another key constraint to PDIA is underestimating the gestation period for policy experiments to show results. However, this applies irrespective of the policymaking structure of a state and has not been discussed further in the current blog.

[4] Kapur A., Irava, V., Pandey S., and Ranjan, U. (2020). “Study of State Finances 2020-21”. Accountability Initiative, Centre for Policy Research. Retrieved from URL: <http://accountabilityindia.in/publication/study-of-state-finances>

Udit is a Senior Research Associate at the Accountability Initiative.