New ideas were at the core of our work in 2019. We invested time and effort in growing our activities and building on ideas with decision makers, scholars and citizens, whose contribution is critical to enabling Responsive Governance. Each project employed rigorous research insights, offered learning opportunities to potential changemakers or sparked dialogues. We invite you to explore some of them.

800+ policymakers reached

Operations in 6 states

Readership of over 15 lakh people through the media

January

11th year of Budget Briefs

Our flagship Budget Briefs series entered its eleventh year of publication with the preparation of two volumes – one during the Interim Budget and the other after the tabling of the full Budget by the new government in July. The Budget Briefs analyse the progress of key welfare programmes of the Government of India, and can be downloaded from here.

February

Launch of a new website for Hindi speaking readers

Committed to making research insights and our practical experience accessible to grassroots development professionals, we launched a new website in Hindi which serves as a one-stop resource on governance. The website shares best practices and facilitates community building among state-based practitioners, an opportunity that they seldom have. A newsletter was also launched in November.

March

Hum Aur Humaari Sarkaar’s ‘Open’ courses

The Hum Aur Humaari Sarkaar learning programme unpacks India’s administrative structure, and the root causes of implementation failure at the last mile of public service delivery. Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) are critical to addressing this gap in service delivery as they can articulate the demands of the people, and hold the state accountable. In all, we organised four ‘Open’ courses in 2019 by publicly inviting applications. Two ‘Open’ courses have been held in Jaipur, Rajasthan. These were attended by a range of participants including: students, participants from Manthan, Pratham, CECONDECON, the Gujarat Mahila Sansthan (a Self-Help Group in neighbouring Gujarat). Other ‘Open’ courses were held in Udaipur, Rajasthan and Patna, Bihar later in the year.

The Hum Aur Humaari Sarkaar learning programme unpacks India’s administrative structure, and the root causes of implementation failure at the last mile of public service delivery. Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) are critical to addressing this gap in service delivery as they can articulate the demands of the people, and hold the state accountable. In all, we organised four ‘Open’ courses in 2019 by publicly inviting applications. Two ‘Open’ courses have been held in Jaipur, Rajasthan. These were attended by a range of participants including: students, participants from Manthan, Pratham, CECONDECON, the Gujarat Mahila Sansthan (a Self-Help Group in neighbouring Gujarat). Other ‘Open’ courses were held in Udaipur, Rajasthan and Patna, Bihar later in the year.

In this podcast you can hear why we believe it is important to engage local development practitioners.

Focus on the next-gen

Through the year we held a series of workshops focussed on the next generation of development leaders. Among them have been Harvard EPoD Fellows; LAMP Fellows; students of Flame University; Bhopal School of Social Service; and the University of Delhi. Session plans have drawn from AI’s research at the frontline over the last 10 years of our existence, and cutting edge scholarly work.

Expansion of PAISA studies

AI has expanded its flagship Planning, Allocations and Expenditures, Institutions Studies in Accountability (PAISA) methodology to include two new areas – nutrition and water. In 2019, an extensive research study tracking processes in implementing publicly funded direct nutrition efforts by the government such as the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) was completed in 6 districts across 3 states. Preliminary findings have been shared with NITI Aayog and also presented to different stakeholders.

April

Federalism and Social Policy

As part of AI’s continued commitment to understanding the evolving nature of federalism in India, and its impact on social policy financing, we contributed a chapter to a special issue of Seminar Magazine. The paper is an extensive review of Union budgets, planning documents, and 20 state budgets and finance accounts. It thus presents a comprehensive account of some emerging trends in central-state relations. The paper can be downloaded from here.

An analysis entitled ‘Towards ‘Cooperative’ Social Policy Financing in India,’ was published in the following month as part of a Centre for Policy Research special series – Policy Challenges: 2019-2024, for the new government. While the practice of using specific purpose transfers dates to the pre-Independence era, over time, Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSSs) have emerged as the primary vehicle through which the Union government finances and directs state expenditure towards national priorities. However, the centralised nature of CSSs often makes them an inefficient tool to address state-specific needs. You can access the full paper from here.

May

Research on India’s fiscal architecture

On the request of the 15th Finance Commission (FFC), AI built on its previous work on Rural Local Bodies (RLBs) or panchayats by conducting two studies to understand the impact of increased devolution to Panchayats by the FFC. The first study was submitted to the Commission in March 2019 and focussed on whether the processes and financial flows from the Union government’s Ministry of Finance for the 13th and 14th Finance Commission period complied with recommendations. The second study undertook a sample survey across Gram Panchayats to understand if money reached the Panchayats, the implications of these grants on Gram Panchayat finances, and how they were spent.

Accountability Initiative 2.0

Among our priorities is providing our digital community with a strong online platform to engage on governance matters. In May, we launched a revamped website, fit-for-purpose to a variety of readers. Among the website’s features are: more engagement options to comment on and share exclusive blogs written by our staff, the option to install RSS feeds, and easy site navigation.

The website forms part of our extensive strategic communications efforts, which you can know about from this blog.

June

Customised learning opportunities

The Hum Aur Humaari Sarkaar learning programme has seen encouraging response from CSOs in 2019. In June, we entered into an institutional partnership with Pratham India to train their state-level staff based on their needs. A version of the learning programme was conducted for staffers of Ibtada, an NGO operational in Rajasthan; and volunteers at Nehru Yuva Kendra in Rajasmand and Hanumangarh, Rajasthan, later in the year.

Our staff also held sessions on the fundamentals of public policy with international NGO World Vision.

Understanding the government’s planning machinery

To unpack planning in the last decade, we engaged with planning secretaries on the changes in the state machinery, specifically looking at the role of the Planning Commission, its dismantling and the subsequent creation of the NITI Aayog.

Deep dive on child budgeting

In June, we participated in workshops on Child Budgeting for development practitioners at UNICEF and Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. Later in the year, we conducted a session for Finance Officers, Government of Odisha on the relevance of earmarking resources for children; Child Budgeting as a policy tool; the methodologies used by Union and other state governments; and global best practices.

July

Unpacking the progress of welfare schemes

Analyses on 10 welfare programmes run by the Union government was published in July. The Budget Briefs covered sectors such as: health and nutrition, education, sanitation, water supply, health insurance, and rural housing and livelihoods. Opinion published in The Wire and The Print can serve as useful contextualisation of Budget-related announcements.

Curating policy news

A new publication curating important news and decisions by the government on welfare policy has been launched. Published every fortnight on AI’s website, Policy Buzz, is a resource for anybody wanting a quick roundup to keep abreast. You can find the latest edition here.

August

A fresh perspective on governance

‘The Edit,’ AI’s monthly newsletter was launched in August. Free of subscription cost, it features exclusive research insights, expert analyses and commentary. Become a subscriber for the latest in public finance, health, education, bureaucracy and current affairs by sending a mail at: [email protected].

Policy in-depth

Apart from publishing papers, we explored Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSSs) in the public forum as well. In the fourth session of Policy In-Depth, our flagship discussion series, we focussed on the role that CSSs have come to play in the Indian welfare system. The session detailed financial planning and fund-flow processes; emerging issues in CSS design and implementation; and the way forward. Policy In-Depth aims to connect scholars with aspiring and mid-level public policy professionals seeking to understand the implementation of India’s major welfare programmes.

Open Data as a tool for accountability in education

Publicly available government data can serve as a useful tool to demand accountability in India’s schooling system. However, our research has shown that the uptake of this data among citizens remains weak. As a first step, we shared our findings with NIEPA scholars, and officials leading Statistics and Management Information System of state education departments and the Samagra Shiksha scheme. A policy brief on the study can be accessed from here.

September

A learning opportunity for aspiring policy practitioners

Our Understanding State Capabilities learning programme was held for students of the University of Chicago Fellowship, and separately for Indian School of Development Management. The course explores the root causes of administrative and fiscal failures, equipping participants to apply a systems approach to on-ground government interventions, and engage with government functioning. The course is conducted in English.

Exploring the potential of emerging technologies in governance

As a panellist, we shared insights on the adoption of technology in governance. The session looked at issues, challenges and proposed solutions to the use of technology in governance and implementation. Organised by the Indian Institute of Public Administration, Delhi the programme included officers of All-India Services, Central Services, Defence Services and the Technical Services.

Another event explored the potential for social accountability in the newly launched Jan Soochna Portal. We contributed to a ‘Digital Dialogue Roundtable’ held by Department of Information Technology, Government of Rajasthan which brought together various departments of the Government of Rajasthan, Soochna Evam Rozgaar Abhiyan (SRA), and Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) among others.

October

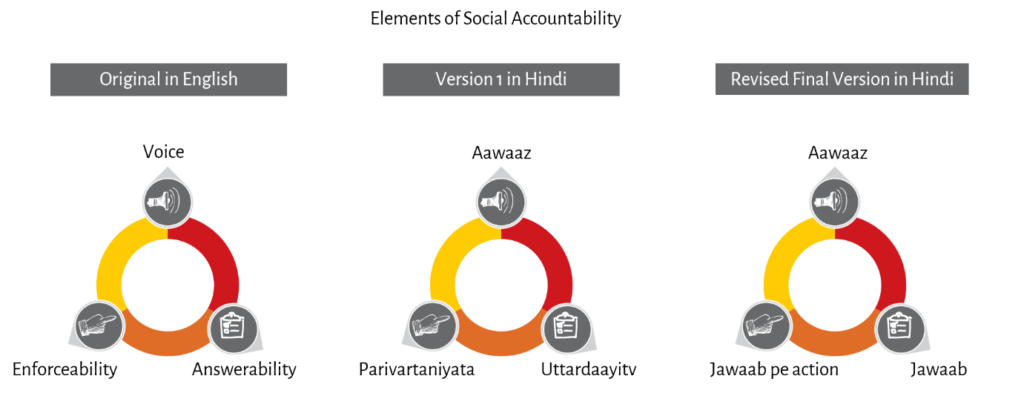

Nuancing accountability

Dr. Jonathan Fox, a scholar of global standing and known for his work on citizen participation, transparency and accountability, visited the AI team in Delhi. He had a wide-ranging discussion on accountability with us, which can be found here.

Understanding school consolidation as a policy tool

The draft National Education Policy (NEP) released in May 2019 has mooted the creation of school complexes for better resourcing of government schools and curbing low student enrollment (see here for our recommendations submitted to the government on the NEP). A school complex will be a single organisational and administrative unit, created by bringing together multiple public schools. Rajasthan is already implementing its version of a school consolidation policy. Our Working Paper was released in 2019, a first-of-its-kind account of this process, and sheds light on the immediate successes and challenges of the policy. We invited research organisations, NGOs, and the media during an event in Jaipur to discuss the policy, and the broader challenges of the public school education system in the state. Details can be found in this blog.

5 years of Swachh Bharat Mission

Over 10 crore toilets or 38 toilets per minute had been built under the Swachh Bharat Mission since its launch in 2014. This unprecedented rise in access to toilets is part of a larger strategy to end open defecation. On SBM’s fifth anniversary, we produced a special podcast where Avani Kapur (Director, AI) and Sanjana Malhotra (Research Associate, AI) discuss whether the goals of the Swachh Bharat Mission have been met. Listen here.

Making citizen participation a part of public policy design

Apart from studying the relevance of social accountability and citizen participation in governance, we also share knowledge with decision makers within the government and CSOs. One such workshop was on weaving social accountability in public policy design. The session was attended by director-level government officials in the Union government at the Indian Institute of Secretariat Training and Management. We also participated in a multi-national event organised by Community of Practitioners on Accountability and Social Action in Health (COPASAH) where we shared ideas on building Responsive Governance.

November

The role of critically evaluating social policy

We conducted a session with the Comptroller and Auditor General’s Advanced Management Group on the importance of probing deeper and considering the why, what and how of social policy evaluations in audit and accounts.

A new addition to our social media portfolio

If you prefer LinkedIn for information sharing over other platforms, our page is now active. This marks a significant addition to the current suite of social media platforms we are currently using to engage with our readers, and is regularly updated with analysis and news that you can use.

December

Comprehensively understanding women and child protection

Since August 2018, AI was mapping the government’s efforts towards the protection of women and children, and preventing violence against them in Maharashtra. Supported by Unicef-Maharashtra, the study concluded in late 2019. Recommendations on formulating legislative measures to improve the system have been shared with the Government of Maharashtra.

As part of another project, we analysed the status and fund flow mechanisms in sample districts of three different schemes over two years (FY 2018-19 and FY 2019-20) with the overall objective of understanding implementation mechanisms and room for improvement. The schemes were: Child Protection Services (CPS), the Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP) under the ICDS scheme, MAMATA scheme of Odisha, and the Rashtriya Kishore Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) focussing on adolescent health in Sitapur, Uttar Pradesh.

Responsive Governance event

We closed the year by hosting the first Responsive Governance Special session with Dr. Gabrielle Kruks-Wisner, an Assistant Professor of Politics and Global Studies at the University of Virginia. Drawing on extensive fieldwork in rural India, she presented invaluable insights into whether, how, and why citizens engage with public officials to secure their entitlements. The findings are published in her book entitled ‘Claiming the State: Active Citizenship and Social Welfare in Rural India’. The event recording can be accessed from here.