A six week drought on the blogging front was not without its compensations; I wandered and connected with people and friends. One of the interesting conversations that I had was on social media groups of my former colleagues in the civil services and the IAS. Social media can be stressful and mind-numbing at its worst and the temptation to walk away is often high. My civil services and IAS group are exceptions, because there is always something to learn, some elevating thought that rises above the usual jokes and banter.

One of the conversations that developed well on these groups was about the successes that were achieved by some of our colleagues. I would not deny that most civil servants are fiercely competitive, driven by the fact that the pyramid narrows at the top, but my colleagues are genuinely generous in their praise of the achievements of others.

That brings me to Kurien.

Anybody who uses the International Airport in Kerala’s commercial capital Kochi, would notice that it is quite an unusual structure. While most airports sport an anonymous façade; of an industrial shed with ultra-luxurious embellishments, Kochi’s airport harmoniously integrates Kerala temple architecture with the needs of a busy airport. The furniture in the domestic terminal comprises cushioned sofas made of wood, which would be more at home in a living room than in a busy air terminal. And busy, it is. Kochi airport is now the fourth busiest international airport in the country in terms of number of international flights and the traffic handled, following Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru.

V.J. Kurien is the Managing Director of the Cochin International Airport Limited (CIAL), the Company that owns and manages the airport. He is currently serving his third term as the Managing Director and his name is synonymous with the airport. The story goes that all you need to mention is Kurien’s name to the taxi drivers in Kochi and they will take you to his home, or office.

So how did it all start? From the start of his career, Kurien earned a name not only for his hard work, but for his capabilities as a bridging individual of high integrity. Kerala is not your typical Indian State and hierarchies don’t work too well. People regard leaders only on their intrinsic merit and there is little bowing and scraping to authority. That often means that decisions are delayed, because consensus should evolve beforehand. Ideas and projects, even good ones, cannot be stuffed down the average Malayali’s throat. Kurien’s affable nature, patience and persistence endeared himself to everybody as a team builder.

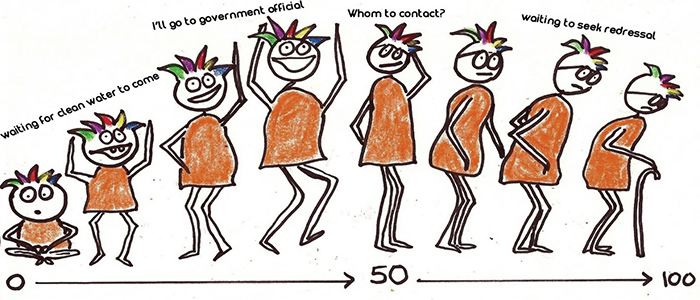

As district collector of Kochi district, Kurien tried to facilitate the expansion of the Naval airport, built on Willingdon Island, a manmade island in Kochi harbor. However, the project was not feasible, due to limited space. Kurien turned his attention further inland and conceived of the idea of building an airport that would be within striking distance of Kochi and Trissur. To overcome the constraints in financing, he proposed a model of public private partnership, with funding drawn from the considerable Keralite diaspora that would benefit from direct international flights into Kerala. However, it is was not easy to commence the project. People in Kerala are passionately attached to their land, and while they all recognised the need for an international airport, they feared loss of livelihood if they were dispossessed of their land. With its culture of mass movements, local opponents to an airport in their vicinity organised themselves well to prevent the project from taking off.

Kerala is not your typical Indian State and hierarchies don’t work too well. People regard leaders only on their intrinsic merit and there is little bowing and scraping to authority.

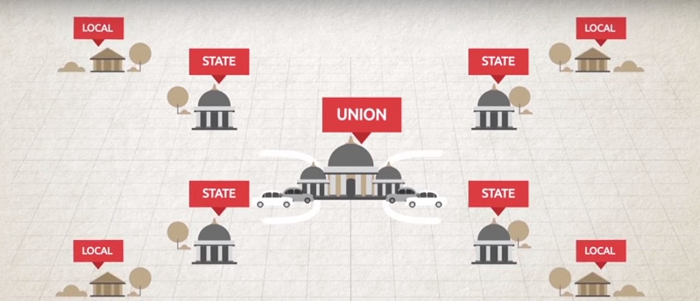

Just when a stalemate seemed inevitable, Kurien was able to obtain the support of the local government in the area, the Nedumbassery Panchayat. Local leaders began to see the sense in the airport coming up in their area, as it would enhance property values. Furthermore, the airport assured all those who would lose their lands for the airport, not only adequate compensation, but also stable employment. The airport, contrary to other similar projects elsewhere, agreed to pay property tax to the Panchayat. None of this would have been possible if it were not for Kurien’s credibility as someone who strived for consensus and peoples’ participation in decisions for the common good.

I will continue the story of Kurien’s success next week.