The debate started with a simple question: How does a society ensure that resources are distributed efficiently and equally to a diverse and heterogeneous society?

We take this question to leading economists and public finance theorists to find the rationale behind it.

Kenneth Arrow, Richard Musgrave, Paul Samuelson: In a democracy, the government is the custodian of my society’s interest and hence should be responsible for maximising my welfare.

Richard Musgrave, Paul Samuelson: In a democracy, the government is the custodian of my society’s interest and hence should be responsible for maximising my welfare.

James Buchanan: But, government agencies are guided by their own self-interests and are no different from individuals. So, it cannot be a single powerful agent seeking to maximize benefits for the society.

Richard Musgrave: However, the government need not be indivisible. There can be different levels where the highest level takes the responsibility of redistributing resources to keep the economy stable. This is important as mobile voters can reduce the potential of redistribution through the lower levels of government.

Wallace Oates: That being said, local level governments continue to play an important role among immobile voters as tastes and preferences vary across regions.

Charles Tiebout: Exactly, and to add there exists a class of goods called the ‘’local public goods’’ for which people effectively sort themselves into homogenous groups. Demands acros s groups vary and therefore I feel decentralized finance holds potential.

s groups vary and therefore I feel decentralized finance holds potential.

Mancur Olson: Smaller groups are likely to be better in attempting collective action as there is less incentive for free-riding at the cost of others. This is because they can be more easily detected. Also, large groups would face relatively high costs when attempting to organize collective action, as compared to local action by small groups. Plus, different levels of government can provide output of public goods whose benefits coincide with the geographical scope of that jurisdiction. And when a service or function can be delivered equally well or better at a lower level, then why do it at a higher level?

Wallace Oates: But hey, there can hardly exist a perfectly coincided jurisdiction with the geographical benefits of public goods. So, there will be spill-over benefits. But then I guess it is still better than uniform, centrally determined level of public outputs.

If we all agree on fiscal decentralisation as a way of better governance, then how should it be institutionalised?

Wallace Oates: If one level of government generates tax revenues in excess of its expenditures, then it can transfer the surplus to another level through inter-governmental grants and revenue sharing. Also, higher order government can give conditional1 grants in the form of matching2 grants where local services generate spill-over benefits for other jurisdictions.

Frank Flatters, J. Vernon Henderson, Peter Mieszkowski: True. Grants are also needed to correct migration patterns and provide desired assistance to poorer jurisdictions.

Wallace Oates: And, unconditional3 grants can be used for fiscal equalization. In the absence of such grants, fiscally stronger local governments can exploit their position to promote continued economic growth, some of which may come at the expense of poorer ones. Besides, the Centre has limited information and are under political constraints to not give generous grants in one jurisdiction over another.

Richard Musgrave: I disagree. I think local public sector should be financed by its own-source revenue like user charges and local taxes such as property tax. Similarly, consumption tax should be left to the States and income tax to the Centre.

Barry R. Weingast, Ronald McKinnon: But local governments should not rely excessively on debt financing because it can destabilize the economy as a whole. Local governments need hard budget constraints.

George Break: One second…and what if competition among local governments for economic development lower the outputs of public services by holding down tax rates?

second…and what if competition among local governments for economic development lower the outputs of public services by holding down tax rates?

Wallace Oates: Nah, local governments compete for mobile resources which not only generates income but also provide taxes for them. Therefore, local governments will try to pull these by adopting efficient levels of output.

Alice Rivlin: I think this competition can easily be tackled with some kind of a revenue sharing mechanism of national taxes which would free the states from worrying about losing business to other states with lower taxes.

After this stimulating discussion, do YOU think fiscal decentralisation is a way forward for better governance?

This view of fiscal federalism as stated above – also known as the First Generation of Fiscal Federalism or FGFF) assumes that public officials seek the common good without considering the behaviour of political agents which also seek to maximise their objectives in a political setting. Moreover, it was limited only to efficient allocative and distributive functions of the government and took for granted issues like asymmetrical availability of information and the existence of an effective political decision making process. Continued debate and exploration on the subject led to the Second Generation of Fiscal Federalism or SGFF which we will cover in our next blog.

** Viewpoints and text of the authors cited above have been edited for simplicity.

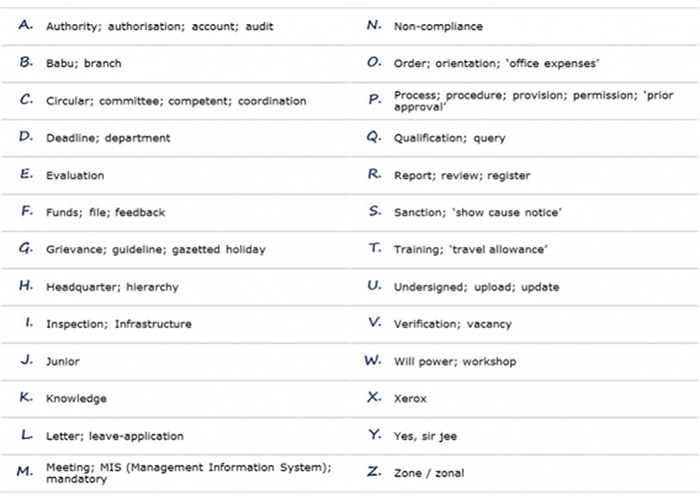

Footnotes

- Conditional grants: These grants place various kinds of restrictions on their use by the recipient.

- Matching grants: Grantor finances a specified share of the recipient’s expenditure.

- Unconditional grants: These are lump-sum transfers to be used in any way the recipient wishes.

References

Arrow Kenneth (1970), “The organization of economic activity: Issues pertinent to the choice of market versus non-market allocation”, in Joint Economic Committee, The Analysis and Evaluation of Public Expenditures: The PPB System, Vol. I (Washington, D.C.:U.S.GPO)

Bird, Richard M. 1999. “Threading The Fiscal Labyrinth, Some Issues In Fiscal Decentralization”.

Brennan, Geoffrey, and James M. Buchanan (1980), “The Power to Tax: Analytical Foundations of a Fiscal Constitution” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Hansen, Alvin, and Harvey Perloff (1944), “State and Local Finance in the National Economy” (New York: Norton)

Inman, Robert P. and Daniel L. Rubinfield (1997), “Rethinking Federalism”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (Fall), 43-64.

McKinnon, Ronald I. (1997), “Market preserving federalism in the American Monetary Union”, (London: Routledge), 73-93

Musgrave, Richard A. (1959), “The theory of Public Finance” (New York: McGraw-Hill).

Musgrave, Richard A. (1983), “Who should tax where and what?” in C. McLure, ED., Tax Assignment in Federal Countries (Canberra: Australian National University), 2-19.

Oates, Wallace E. 1999. “An Essay on Fiscal Federalism”. Journal of Economic Literature 37 (3): 1120-1149.

Oates, Wallace E. 2005. “Toward A Second-Generation Theory of Fiscal Federalism”. International Tax and Public Finance 12 (4): 349-373.

Olson, Jr., Mancur (1969), “The principle of Fiscal Equivalence: The Division of Responsibilities among different levels of government”, American Economic Review 59, 479-87.

Samuelson, Paul A. (1954), “The pure theory of Public expenditure”, Review of Economics and Statistics 36 (Nov.), 387-9.

Tiebout, Charles (1956), “A pure theory of local expenditures”, Journal of Political Economy 64 (Oct.), 416-24.

Weingast, Barry R. (1995), “The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-preserving federalism and Economic development”, Journal of Law and Economic Organization 11, 1-31.

Richard Musgrave, Paul Samuelson: In a democracy, the government is the custodian of my society’s interest and hence should be responsible for maximising my welfare.

Richard Musgrave, Paul Samuelson: In a democracy, the government is the custodian of my society’s interest and hence should be responsible for maximising my welfare. s groups vary and therefore I feel decentralized finance holds potential.

s groups vary and therefore I feel decentralized finance holds potential. second…and what if competition among local governments for economic development lower the outputs of public services by holding down tax rates?

second…and what if competition among local governments for economic development lower the outputs of public services by holding down tax rates?