School Education Financing Needs Rethink in the Current Fund-Crunch Situation

15 July 2020

India’s public school education system is currently confronting multiple challenges. First, the urgency to adapt to ICT-enabled modes of education delivery during the extended months of school closure. Second, a fund-crunch situation fuelled by a steep drop in government’s revenue collection during COVID-19, exacerbated by an unprecedented demand for funds to fight the health crisis. School education financing will have to be rethought by States to identify priority areas that are non-negotiable based on their needs.

A recent report by the Accountability Initiative at the Centre for Policy Research provides insights on expenditures incurred by eight State governments on school education from financial year (FY) 2014-15 to FY 2017-18. We have found that the average expenditure incurred per-student varies widely across States. But, as COVID-19 upturns traditional classroom-based schooling, resources will be needed to continue education with relevant digital means and health safety protocols. For such future financial planning to take place, it will be important to understand how different States have financed school education in the past.

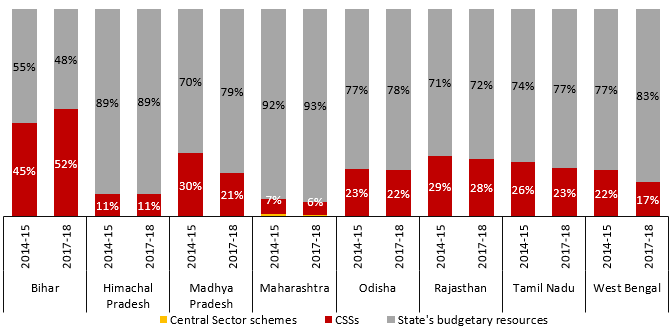

Apart from their own budgetary resources, States rely on Central Sector (CS) schemes and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSSs) to fund school education. While CS schemes are fully funded by the Union government, CSS funds are shared between the Union and the States in a 60:40 ratio for most States.

Figure 1: Distribution of school education expenditure across instruments of financing (%)

At present, the two major CSSs related to school education are Samagra Shiksha and Mid-Day Meal (MDM). Samagra Shiksha (implemented since FY 2018-19) has unified three of India’s longstanding education programmes – the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA), and Teacher Education (TE). Our analysis shows that some States rely on CSSs more than others. For example, in FY 2017-18, while CSSs made up 52% of Bihar’s school education spending, the share for Maharashtra was only 6%.

Moreover, as the report reveals, the provision of elementary education is dependent on CSSs than secondary education in most States. In Rajasthan, for instance, CSSs constituted 56% of elementary and 6% of secondary education expenditure in FY 2017-18. Therefore, any suspension in CSS spending is going to impact elementary education more.

It is important for States to access these funds in the current revenue-crunch situation for two reasons. Firstly, as the financial burden for CSSs is shared by the Union, it would be relatively easier for States to access these funds by contributing a smaller share. Secondly, there is limited scope to play around with States’ own budgetary resources as the majority is spent on committed liabilities such as paying teacher salaries. Since CSSs have been observed to give relatively higher importance to aspects such as incentives to students, school infrastructure, quality etc., they might provide more room to reprioritise in the future.

School education financing will have to be rethought by states to identify priority areas that are non-negotiable based on their needs.

However, the pandemic has introduced fresh challenges. The Department of School Education and Literacy under the Education Ministry has been asked by the Finance Ministry to restrict expenditure in the first quarter of FY 2020-21 to 15% to 20% of Budget Estimates (BEs). Generally, during the first quarter, the Department releases the first batch of installments for most schemes and can ideally spend at least 25% of total budgets allocated for that year. This decision is likely to result in a decline in funds approved for the States. To illustrate, for FY 2020-21, the total approved allocation for Samagra Shiksha by the Education Ministry is Rs. 8,000 crore for Bihar (which was Rs. 8,625 crore in FY 2019-20) and Rs. 5,700 crore for Rajasthan (which was Rs. 6,297 crore in FY 2019-20).

Even though overall budgets approved are likely to decline, the Union government probably won’t cut central shares of whatever is approved for the flagship schemes. However, the challenge for States would be to avail these central shares. A necessary condition for a State to utilise CSS funds is to add in their respective shares to the central shares released. States are presently finding it difficult to contribute their shares, which is creating uncertainty around eventual utilisation.

This is a major concern for States like Bihar that are highly dependent on CSSs. The Bihar government recently requested the Union government to bear both State and Central shares in all CSSs. Even for States like Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, where around 20% to 30% expenditure was funded through CSSs in FY 2017-18, this is a concern. All government departments in Odisha were recently asked not to spend any CSSs funds unless they received the corresponding Central shares.

Given the potential drop in funds available for States through the CSS route or otherwise, there is an urgent need to rethink planning and financing for school education by the states to ensure efficient education delivery through ICT-enabled modes and address related access issues. ICT infrastructure, teacher training, school management committee training etc. are some areas that require immediate attention. One of the ways to achieve this is by giving greater flexibility to States by the Union government to use CSS funds as per their needs, which is otherwise not possible since CSS funds are tightly earmarked for pre-decided activities at the approval stage itself.

To cite this blog, we suggest the following: Bordoloi, M., Pandey, S. & Irava, V. (2020) School Education Financing Needs Rethinking in the Current Fund-Crunch Situation. Accountability Initiative, Centre for Policy Research. Available at: http://accountabilityindia.in/blog/school-education-financing-needs-rethinking-in-the-current-fund-crunch-situation/.