The Grey Area of Professional Corruption

1 July 2019

In my blog of 14 June, I referred to the phenomenon of private sector corruption and listed four categories of such corruption. One of the important areas of private sector corruption is the corruption engaged in by those in professional occupations in the private sector.

It is difficult to define Professional Corruption with any degree of precision, for two reasons. First, as private sector corruption is not criminalised, there is no definition of the kinds of corruption that is engaged in by professionals in the private sector. Second, many of those who carry on occupations of professionals holding a position of a fiduciary nature in the private sector, do not even think that what they engage in constitutes corruption. They at worst, think of what they do as a business sharp practice, never corruption.

What exactly do I mean by those who are in fiduciary positions? By this, I refer to doctors, media persons, chartered accountants, lawyers, company secretaries and such like. These professions are governed by strict codes of conduct; indeed, these can be considered as codes of honour, to which professionals who practice these are to strictly comply. These professionals are also governed by voluntary associations of themselves, such as the Institute of Chartered Accountants, the Bar Councils, the Indian Medical Council and the Press Council. These professional bodies lay down the yardsticks to define integrity with reference to their respective areas of professional skill. Violation of these codes of conduct can lead to various degrees of punishment, which depend upon the extent to which unethical and corrupt acts of those belonging to the guild constitute unacceptable behaviour.

In the case of lawyers, for example, a transgressor of the do’s and don’ts of conduct laid down by the Bar Council, can be punished through censuring, or in the most grave of cases, with deregistration and the withdrawal of permission to practice in various courts. In the case of doctors too, there can be a withdrawal of registration, which results in those de-registered not being able to carry out their practice as doctors.

Are these effective?

Not by a long shot, even though the extent of compliance can vary from one profession to another. Two examples will suffice to show the patterns of compliance or lack of it, in selected professional guilds.

The first case study is of corruption in the health sector, and in particular, that which is prevalent amongst doctors, both as individuals and as part of an institution.

The health sector has been identified in many countries as being relatively more prone to corruption. In developing countries, this is often attributed to the fact that health services are in great demand, while the resources to provide adequate services are often inadequate, leading to a premium on their availability. This can also be attributed to the relative concentration of medical services in urban areas in such countries, which drives rural people to come to urban areas for treatment, where they are more vulnerable to fall prey to demands for bribes.

Extent of Corruption in the Health Sector:

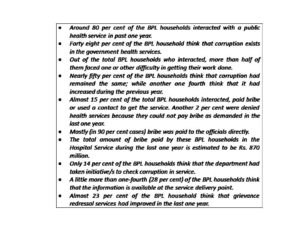

According to the India Corruption Study 2007 undertaken by Transparency International and the Centre for Media Studies, Health stands at the seventh position in terms of most corrupt services, out of 11 studied. (Above health comes, Police, Land Records/Registration, Housing, Water Supply Service, NREGS, Forest and Electricity. Health ranks worse than PDS, Banking and School Education). The corruption in the sector is mostly to do with non-availability of medicines, getting admission into hospitals, consultation with doctors and availing of diagnostic services. In particular, the survey revealed the following particulars (Box 1):

More about health sector-related corruption in my next blog.

This blog is part of a series. The first blog can be found here.