Trickle or Flow: Unpacking Fund Flow Pattern of Jal Jeevan Mission

18 May 2022

Launched in August 2019, Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) aims to provide functional household tap connections (FHTCs) to every rural household in India by 2024. At the start of the mission, 83 per cent rural households did not have any FHTCs. Three years later, and two years away from the deadline, 51 per cent of households are yet to receive FHTCs.

On investigating the progress of the scheme, we discovered that despite an increase in allocations every year, releases of funds (for the mission) to states have been constantly decreasing. In this blog, we unpack the possible reasons for the slow releases and their implications for the scheme.

What is the Jal Jeevan Mission trying to achieve?

A decentralised and demand-driven project, the mission shifts the focus of water supply from a group of houses (habitations) to individual households, and is trying to ensure potable water supply to all villages in India. Priority is given to villages in areas that have poor water quality, and drought-prone and desert areas. Besides households, JJM also takes into account providing FHTCs to schools, Anganwadi centres, Gram Panchayat buildings, Health and Wellness centres, and other community buildings.

While providing FHTCs is the primary goal of JJM, monitoring the functionality of already-installed tap connections, water quality surveillance, and ensuring the long-term sustainability of water supply systems also comes under the purview of this mission.

How are fund releases planned and how slow are the releases?

Prior to receiving funds, states need to prepare ‘State Action Plans’ (SAPs) after collating plans at the village and district levels. These SAPs are submitted to the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, which is the nodal department for the mission, along with other planning documents. Allocations and releases are then deliberated upon and dates are decided for the releases in different quarters of the year.

The fund sharing ratio between the Union government and the states is different for each component within the scheme. For example, the ‘Coverage’ component is shared in a 50:50 ratio while for ‘Water Quality Management System’ the ratio is 60:40. For states in the North Eastern Region (NER), funds are shared in a 90:10 ratio.

Releases for JJM take place in two instalments. The first instalment of 50 per cent of the total allocation is released in two equal ‘tranches’. The first tranche is released based on the opening balance as reflected on the Public Finance Management System (PFMS). The second tranche is released after 80 per cent of the first tranche is utilised. The second instalment is released in two tranches too. States are expected to upload Utilisation Certificates (UCs) and seek approvals from the Auditor General as well in order to receive funds.

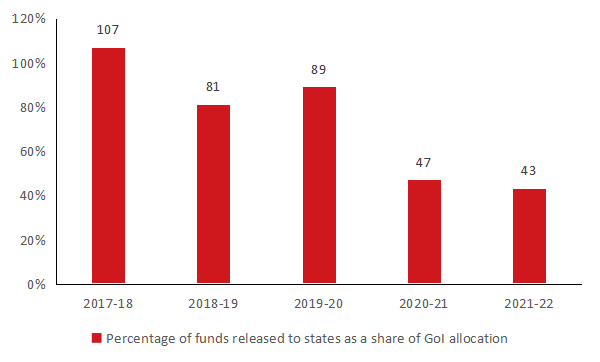

Since FY 2019-20, the pace of fund release for JJM has deteriorated significantly. A mere 47 per cent of funds were released in FY 2020-21 and this further declined to 43 per cent in FY 2021-22.

Figure 1: In 2021-22, only 43% of GoI’s share had been released

Understanding the processes involved in releases point at a common challenge many public schemes in India face — sluggish progress on account of procedural bottlenecks at all possible steps in receiving releases.

Why are the releases for Jal Jeevan Mission slow?

Improper utilisation of the funds provided for the mission is a major reason for the delay. This occurs when states take time to submit their UCs of the initial funds released. In other words, a lag in the submission of such receipts and certificates results in a significant delay in the subsequent release of funds to states.

Also, funds may be released later in the financial year if states have large opening balances carried over from the previous financial year. This opening balance is otherwise subsumed initially during the first release.

In addition, the slow release of a state’s portion of the funds for the mission can also result in a slow release of total funds for Jal Jeevan Mission. For example, in FY 2021-22, Andhra Pradesh released a mere 17 per cent of its matching shares to that of the central share.

States may also have their own drinking water supply schemes which lead to JJM finances entering muddled spaces. An example is Telangana’s Bhageerathi Mission which has received large allocations from the state’s own funds. In FY 2021-22, Telangana did not withdraw any funds allocated by the centre. In addition to higher state allocations for the Bhageerathi Mission’s objectives, the state saw funds being merged with that of JJM. In such cases, the probability of procedural complications and delays is higher.

What are the implications of low releases?

It goes without saying that the effects of lag in releases are experienced the most during grassroots implementation where the installation of necessary tap connections does not take place due to arrears in payments and lack of funds. To achieve ambitious goals such as ensuring functional tap connection for every household, following financial discipline is a necessity. Following this discipline ensures better management of tasks to be completed and newer ones to be taken up.

The release of grants for large schemes must follow the financial rules enforced by the Department of Expenditure at the Ministry of Finance better. These rules specify that after creating the necessary demand for grants, the state governments must transfer the Central share within 21 days to the implementing agency within the state and release its own share within 40 days of the release of the Centre’s share.

The current Management Information System (MIS) that monitors Jal Jeevan Mission’s fund releases and expenditures does not report low releases and the following action to be taken. With the Union making large commitments through Centrally Sponsored Schemes, it has been recommended by multiple expert committees that independent evaluators not involved with the implementation must be made part of the progress monitoring process.

In all, with less than two years for the scheme to meet its targets, both the Union and the states must work towards releasing a higher quantum of funds and ensure spending on necessary components.

Understanding the processes involved in releases point at a common challenge many public schemes in India face — sluggish progress on account of procedural bottlenecks at all possible steps in receiving releases.

Also Read: Making the Government System Climate Change-ready