How Secure are Construction Workers?

1 April 2020

Construction workers have been out of employment due to the countrywide lockdown to combat the Coronavirus pandemic. On 24th March, the Government of India directed all states and Union Territories to make use of unutilised cess funds created for the welfare of such workers. The aim is to provide them some relief and financial assistance. A look at the cess fund utilisation pattern for the delivery of welfare services till now is revealing.

Construction cess is imposed on construction projects, applicable to any establishment engaging 10 or more workers and to projects costing more than ₹10 lakh. State-level Construction Workers’ Welfare Boards pay social security benefits to workers who register with them. Workers aged between 18 and 60 years who have participated in building or construction work for at least 90 days in the preceding 12 months are eligible to register.

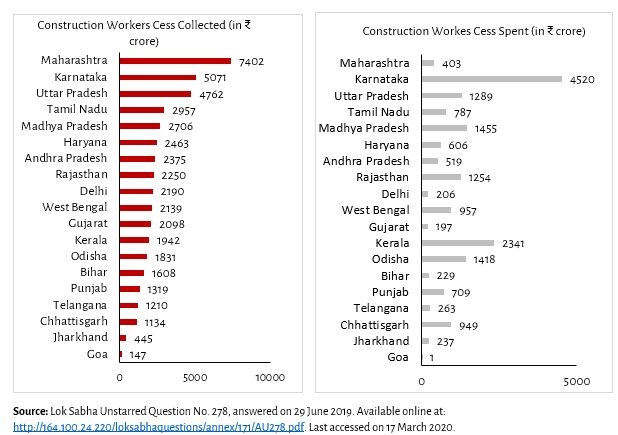

An amount of ₹49,675 crore of cess was collected by states and UTs till March 2019, but only 39% (less than ₹20,000 crore) has been utilised. There are wide differences among states. As many as 21 of the 37 states and UTs spent less than 30% of their collected funds. Kerala was the only state to have spent more than the collected funds (121%). But states which collected the highest amount of cess have spent the least on the welfare of construction workers. For instance, Maharashtra spent only 5% of ₹7,402 crore that it had collected. Similarly, Delhi collected ₹2,190 crore, but spent only 9% of the amount. Goa (1%) and Gujarat (5%) had the lowest utilisation of funds.

The welfare boards were established in states and UTs to regulate the conditions of construction workers under the Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Condition of Services) Act passed by the Parliament in 1996. They were supposed to regulate working hours, provide drinking water, crèches, first aid, canteens etc. and ensure safety and health measures. The Act was the result of a decade long struggle of workers between 1985 and 1996.

The Parliament also passed another legislation viz. the Building and other Construction Workers’ Welfare Cess Act, 1996, which empowered the states and local authorities to levy and collect cess on the construction costs incurred by employers, government, public and private companies. The rate of cess imposed was envisioned to be not more than 2%, and not less than 1%. This is the cess that is passed on to welfare boards.

With low fund utilisation, however, it is unlikely that welfare boards have been able to deliver the proposed benefits to construction workers. But the need for protection measures was immense even before the Coronavirus pandemic began.

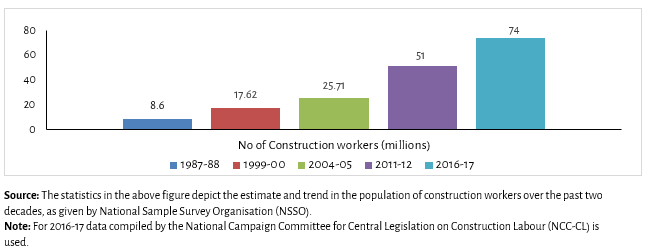

As per the National Sample Survey Organisation (2016-17), there are an estimated 74 million construction workers across the country. They come from poor economic and social backgrounds, usually lack education and have poor vocational skills, if at all. Poverty, illiteracy and poor language skills often contribute to their weak bargaining power when it comes to employment. This is exacerbated by a general lack of awareness of their rights with respect to minimum wages, working conditions, social security benefits and government welfare schemes. They are majorly employed in constructing roads, highways, flyovers, metro rails, malls, residential housing, etc.

A new Labour Code on Social Security and Welfare by the Government of India is in the offing, and seeks to replace 15 laws on social security (including the BOCW Act). Many benefits presently accessible under the Act may not exist under the new code, and revoking it can have a catastrophic effect on construction workers as registrations of workers will lapse. There is already a huge gap between the estimated number of construction workers and registered workers with welfare boards (less than 50% of estimated workers are registered with such boards). Further down, it will also lead to the closure of 37 State and UTs BOCW boards and workers will have to again enrol themselves with the suggested state welfare boards. These newly formed state boards will also consist of other unorganised sector workers, and all of them will be listed in the same place. Moreover, the cess collected for the construction workers would go into a shared social assistance fund.

Thus, as the Coronavirus pandemic exposes construction workers to a difficult future, there is a need to reexamine what can be best done to secure them. This will require critical assessment of why less than half of the funds meant for their welfare have remained unspent in the first place.

References:

Katole H. (2016). A study of contract labour at a real estate and construction company. International Journal of Management. 7(3)

Moavenzadeh, F. (1978). Construction industry in developing countries. World Development, 6(1), 97- 116.

Mahajan, K. (2018). Rural Construction Employment Boom during 2000-12.

Prasad, R. S., Rao, K. V., & Nagesha, H. N. (2011). Study on building and other construction workers welfare schemes/amenities in Karnataka. SASTech-Technical Journal of RUAS, 10(1), 59-66.

Sharad is a Research Associate at Accountability Initiative.

Editorial inputs by Avantika Shrivastava