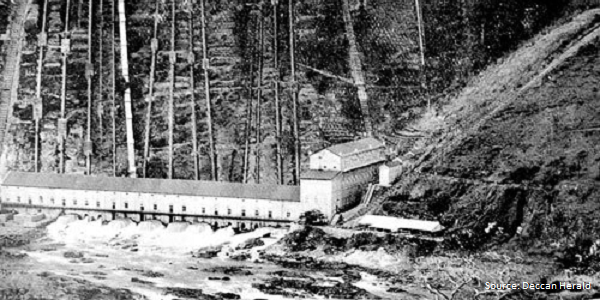

What it Took to Construct India’s First Hydroelectric Power Station

6 September 2019

Last week, I described the procurement process for the construction of the first hydroelectric power station built in India, at Shivasamudram in Karnataka, in the last years of the 19th Century. In this blog, I look at the complex government negotiations for constructing the station.

Even as the necessary approvals were secured for the selection of General Electric as the main contractor for the supply and commissioning of the electricity generation equipment, the Government of Mysore worked on settling the contracts through which they would sell the power they generated to customers. The main focus was to replace the steam power that ran the Kolar Gold Fields with cheaper and more efficient electric power. For this purpose, a 10 year agreement was entered into with the mines. This agreement provided for commercial terms and conditions and the modalities of power transmission and distribution within the mining area. The government extended its responsibility beyond installing the power generation and transmitting equipment, to purchasing and supplying the distribution plant to work the mining machinery. Even today, the transmission station built more than a century back, owned by the government, exists at the Kolar Gold Fields.

One of the key points to remember is that even as large scale infrastructure projects of this nature are constructed, simultaneously the return in these investments have to be worked out. In the case of the sale of power to the Kolar Gold Fields, the rates for the 4,000 HP promised to be supplied was fixed and graduated on the basis of an equitable return on capital, interest and profit, as at the end of a period of successful operation. The rates were gradually proposed to be lowered over time, as it was anticipated that the power demand would grow. The agreement provided how payments would be affected by interruption of power from any cause. The assurance to provide the contracted power was also matched by a corresponding assurance that the mine could not discontinue the use of power for the load that it assured. Work began in earnest on the construction of the project. After the first year’s working, the government was to hand over the distributing plant to the mines, free of cost.

It took a lot of hard negotiations for the agreement to be finalised. The seventh draft agreement was approved by the Government of Mysore and the mines, after which the approval of the Government of India was obtained.

The issue of water sharing was as live then as it is now. Since the Cauvery river for some distance above the waterfalls fell partly in Madras Presidency, the Madras Government had to be consulted on the terms and conditions of water use for power generation. The Mysore government justified its preferential claim to the water on the grounds that it was the first to investigate using the power potential, that it was prepared to carry out the construction utilising state revenue, and that the water at the falls came almost entirely for Mysore territory. Its utilisation of the river for power generation would not interfere with any existing interests in Madras Presidency.

The Mysore government also enlisted the support of the Government of India and the Viceroy for its proposal. After protracted negotiations also involving the Government of India, the Mysore and Madras governments entered into a concession agreement that stated out their rights on water use. Under this agreement, the Mysore government secured the rights to control the discharge in the river and its branches at and above the falls, and to utilise the whole power of the falls. It also undertook to respect existing legal rights for using water for irrigation and other purposes by the Jaghirdar of Shivasamudram and other private persons while reserving to itself a first right of refusal over the construction of new irrigation works that would diminish the water flow in the river. In order to address some of the above concerns, further changes were made in the technical conception of the project.

Once the complications regarding the sale of power and the rights over water were out of the way, attention shifted to the engineering aspects of the project. Being a hydroelectric project, the availability of adequate water was very crucial. At one heart stopping time, doubts arose where the water available was enough to generate the power required to transmit and deliver 4,000 HP at the mines. Briefly, the government toyed with the idea of supplementing a likely deficiency in hydroelectric power with steam power. After a thorough investigation of the water flows upstream, including an examination of the Madhava Mantri dam twenty miles above the falls, water sufficiency was conclusively established and the steam plant idea was dropped.

Simultaneously with the paperwork, local works were started on 16 August 1900 in the malaria infested jungle that surrounded Shivasamudram. The Cauvery was in high flood when construction started. Almost all the labour force of 5,000 people was brought in from elsewhere. For better mobility of men and material, a central depot was established near the Bangalore city Railway Station and a Tonga service was started between Maddur, the closest railhead, and Shivasamudram. Road transport of the heavy equipment from Maddur was undertaken through special imported road trolleys, with eight huge state elephants from the Mysore government doing yeoman service along with teams of bullocks. A material tramway was also completed on the face of the bluff to move material into the gorge.

Thus, it took a lot of hard negotiations for the project to be finalised.

Also Read: A Testimony to Integrity in Procurement