COVID-19 Response: Why Repackaged Health Spending Promises Offer Nothing New

27 May 2020

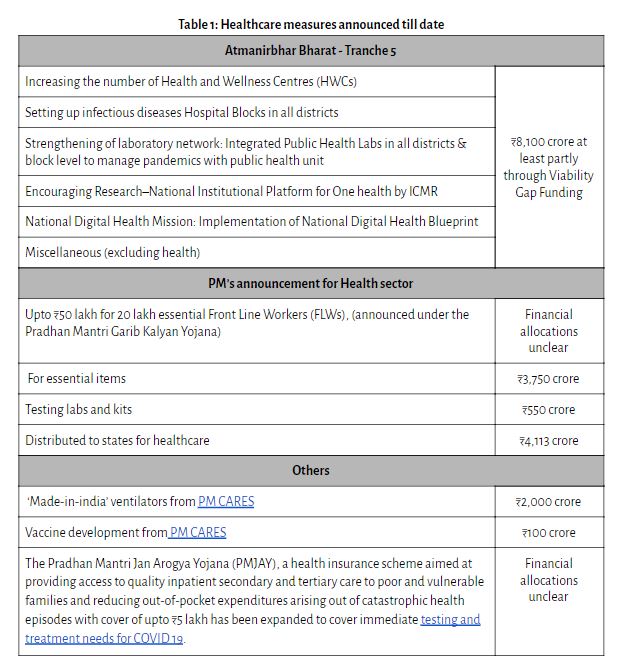

Breaking the silence on specific measures to increase health expenditure and infrastructure on 17th May, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman made health one of the key focus areas for the fifth and last tranche of the stimulus package under the Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-Reliant India) Yojana. Stating the need to ramp up public expenditure on health by focussing on strengthening investments at the last mile – particularly districts – the package included an allocation of ₹8,100 crore for increasing social infrastructure including Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs), at least partly through viability gap funding [1]. This announcement follows the previous announcements of ₹15,000 crore of which a portion is to be used for providing health insurance cover to essential Front Line Workers (FLWs); procuring essential items and kits, and establishing testing labs. Further, ₹4,113 crore has been distributed to states for healthcare, and the rest is to be used over the next one to four years. (See Table 1 for more details).

Yet, a closer look at the measures suggests that most had already been announced by the Government previously and thus do not offer anything new or radical, despite an ongoing public health emergency. Let’s look at some of these one by one.

Increasing Health and Wellness Centres

A focus on primary care through Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) has been a key priority of the government under the Ayushman Bharat scheme. Between FY 2018-19 and FY 2019-20, allocations increased 33 per cent from ₹1,200 crore in 2018-19 to ₹1,600 crore in 2019-20 Revised Estimates. Another ₹1,600 crore was allocated for this fiscal year. With over 40,000 HWCs completed till March 2020 and another 30,000 planned for this year, we are well on our way to meeting the target of building 1.5 lakh HWCs by 2022. But the larger question of how these HWCs will be able to respond to the pandemic remains unanswered. Currently, in the absence of an accessible HWC, most rural Indians rely on either private facilities or a network of primary health facilities including Sub-Centres (SCs), Primary Health Centres (PHCs), and Community Health Centres (CHCs). Data available in the latest Rural Health Statistics 2019 however reports that only 3% SCs, 8% PHCs and 22% CHCs function as per Indian Public Health Standard norms and in fact, the proportions have been falling yearly.

Building Hospitals in Aspirational Districts

The second key announcement of building infectious diseases hospitals in aspirational districts, also follows the one made in the Union Budget speech in February which called for increasing the hospital network in aspirational districts which didn’t have PMJAY empanelled hospitals. This was to be done in Public-Private Partnership (PPP) via viability gap funding, similar to the announcement made this time. The introduction of an additional 5% health cess on custom duty for medical equipment was to be used to support this vital health infrastructure. The main change thus is the additional gross budgetary support that will be needed, given that taxes on essential devices for COVID-19 treatment have now been removed. A lack of transparency on the details of the viability gap funding and of PM-CARES, however, means that the exact quantum coming from the Union government versus private players remains unclear.

Strengthening of laboratory network

The third announcement – which appears to be more directly linked to the pandemic – was the call to increase laboratories. As on 25 May 2020, a total of 612 labs comprising a network of 430 government and 182 private laboratories are conducting various COVID-19 diagnostics. The influx of workers returning home from cities, is going to require additional laboratories (and fast) not just in urban areas, but also in rural areas. While the announcement takes a step in recognising this need, here too, a look at the operation guidelines of HWCs suggests that these were already part of the plan. More importantly, difficulties in operationalisation has meant that as of September 2019, the number of diagnostics that could be conducted at HWCs converted from existing PHCs ranged from as low as 7 in Bihar to 63 in Manipur. Add to this the sheer absence of lab technicians across many PHCs (more than half the required posts are vacant), it is unclear how the government will be able to tackle existing operationalisation concerns amidst the need to expand capacity fast, including with an additional specialisation for COVID-19 testing.

Training Medical and Paramedical Workers and Others

Then there were the other announcements, from ensuring training to medical and paramedical workers, to the National Digital Blueprint for digitising patient records, and increasing health insurance cover to frontline functionaries. With the exception of the added health insurance, the first two were again already part of the Government’s original plan. The Budget speech in fact had stated the need to match skill sets with employers standards, given the “huge demand for teachers, nurses, paramedical staff and care-givers abroad”. It had thus proposed that “special bridge courses be designed by the Ministries of Health, Skill Development together with professional bodies to bring in equivalence.” Data on the number of frontline workers trained recently is not publicly available but interviews conducted by us with various functionaries have reported receiving relatively little training with respect to their new COVID-19 specific task requirements, including things like uploading data for active cases, amongst others. Similarly, the draft National Digital Blueprint was first announced by the National Health Policy and placed in the public domain in April 2019. The fact that most of these are repackaged erstwhile announcements is clear given that for most of these measures, associated fiscal costs have not been specified.

A closer look at the measures suggests that most had already been announced by the Government previously and thus do not offer anything new or radical, despite an ongoing public health emergency.

Increasing Public Health Expenditures

Last of course was the slightly vague announcement of increasing public health expenditure. Given the low levels of spending in the past – last year only 1.6% of India’s GDP was spent on health by the Centre and States combined – the importance of increasing public health expenditure goes without saying. Yet despite the National Health Policy calling for an increase to 2.5% of GDP, responses by both Union and State governments have been less than adequate. The Union government’s investments in healthcare have remained low – with budget allocations for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare increasing only 4% in 2020-21 Budget Estimates (BEs) compared to the Revised Estimates (REs) from last year. Moreover, as per a report on state finances by the Accountability Initiative at the Centre for Policy Research, the percentage of health expenditure among 17 states has remained well below 2% and has, in fact, declined this year for some states. The bulk of this expenditure has been on paying salaries. Capital expenditure (used for building health facilities) has been a meagre 10-15%.

There is no question that there is an urgent need to ensure adequate finances not just for dealing with the immediate pandemic but other pressing health concerns as well. Every day, 1,000 people in India die due to Tuberculosis alone, another 1,935 children under 5 die due to malnutrition. While details of the PM-CAREs fund aren’t publicly available, media reports indicate that only ₹2,100 crore has been dedicated to health so far through the ₹ 9,677.9 crore ($1.27 billion) fund for ‘Made-in-India’ ventilators (₹2,000 crore) and vaccine development (₹100 crore). At this critical juncture, with the number of COVID-19 cases nearing 1.5 lakh (as on 26 May 2020) healthcare must be prioritised and financed through this massive corpus of funds.

For the Union government, this also means ensuring adequate funds reach States in a timely manner and supporting states in developing disaggregated data systems for reviewing health outputs and outcomes. The members of the government and bureaucracy have their work cut out for themselves, in trying to balance the needs of the pandemic whilst maintaining existing healthcare needs. Moving forward, let’s hope there is more creative thinking on how to manage something unprecedented in India: massively increasing healthcare spending.

[1] Grant to support projects that are economically justified but not financially viable, typically used to support public-private partnerships.

To cite this blog, we suggest the following: Kapur, A. and Shukla, R. (2020) COVID-19 Response: Why Repackaged Health Spending Promises Offer Nothing New. Accountability Initiative, Centre for Policy Research. Available at: http://accountabilityindia.in/blog/covid-19-response-why-repackaged-health-spending-promises-offer-nothing-new/.