India’s Public Distribution System in the Pandemic

26 August 2021

This blog delves into the importance of the Public Distribution System (PDS) during the COVID-19 pandemic, and its functioning.

What is the Public Distribution System?

The PDS system in India, with its focus on the distribution of foodgrains, took shape in the 1960s due to a critical shortage of food. In June 1997, the Government of India launched the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS), which was linked to poverty estimates. Under the PDS, states were required to formulate and implement foolproof arrangements for the identification of eligible beneficiaries for the delivery of foodgrains, and for grain distribution in a transparent and accountable manner at the level of the Fair Price Shop (FPS).

The National Food Security Act (NFSA) enacted in the year 2013, delinked the coverage under TPDS from erstwhile poverty estimates. Eligible households/beneficiaries under NFSA comprise the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) households and persons belonging to Priority Households (PHH) categories. As per NFSA norms, among Priority households, each member is entitled to 5 kgs of grain per month at Rs. 2/kg for wheat and Rs. 3/kg for rice. Antyodaya households get 35 kgs/month at the same price, irrespective of family size.

Coverage under NFSA was linked to the population estimates and inter alia entitles up to 75 per cent of the rural population and up to 50 per cent of the urban population for receiving subsidised foodgrains under the TPDS. It thus covered nearly two-thirds of the country’s population.

How does the PDS System in India work?

There are two systems of procurement of foodgrains: a Centralised Procurement System (CPS) and a Decentralised Procurement System (DCP). Under the CPS, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) is responsible for the procurement, storage, transportation, and bulk allocations of foodgrains to state governments. Under the DCP, state governments undertake direct purchase of foodgrains, and are also responsible for the storage and distribution under NFSA and other welfare schemes.

Foodgrains are procured from farmers by FCI or a state government, depending on the procurement system in place, at government notified prices known as the Minimum Support Price (MSP). The total cost of procurement is then MSP plus other incidental costs such as transportation. The foodgrains are then sold by FPS at a subsidised price, which is called the Central Issue Prices (CIPs). The difference between the total cost of procurement and CIP is reimbursed by the GoI to FCI (in the case of CPS) and states (in the case of DCP) as food subsidy.

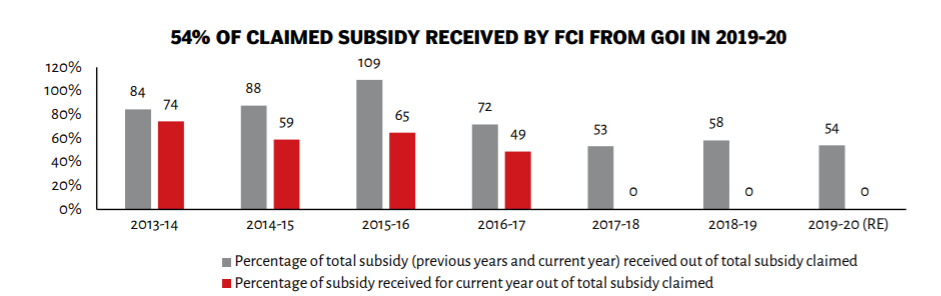

The PDS system faces several challenges and bottleneck issues. Firstly, over the past few years, there has been an increasing gap in GoI’s allocation for food subsidy and reimbursements claimed by the FCI.

Source: Food subsidy released and due for FCI. Available online at: https://fci.gov.in/finances.php?view=22. Last accessed on 26 January 202

Consequently, since 2013-14, FCI’s debt has increased almost four times. The outstanding debt at the start of the FY 2020-21 stood at more than 3 lakh crores as on 31 December 2020.

Secondly, there are significant exclusion errors with eligible beneficiaries not being able to access PDS. The current calculations of eligible beneficiaries is based on the 2011 Census data. Since 67 per cent of the population is to be covered under NFSA, according to the 2011 Census, the number of beneficiaries to be covered comes up to 81.4 crores. However, this calculation does not take into account the population growth over the last decade. If we take the 2020 projected population as per the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, an additional 10 crore beneficiaries should be covered under the NFSA.

Importance in the Pandemic

The global COVID-19 pandemic has overwhelmed India’s health infrastructure and disrupted the economy. Additionally, recent data on malnutrition paints a worrying picture. India has one of the highest proportions of undernourished children in the world, in terms of both stunting and wasting. Moreover, the National Family Health Survey 2015-16 and 2019-20 rounds show that there is either a stagnation or worsening of several malnutrition indicators in several states. (The NFHS-5 data pertain to the situation before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.)

Studies have shown that households continued consuming less food several months after the nationwide lockdown in 2020, than before it. A survey by the Centre for Sustainable Employment at Azim Premji University found that over 75 per cent of the households were eating less during the lockdown than before it. There was a slight recovery post-lockdown, but 60 per cent of the households still reported eating less than before the lockdown. Moreover, disadvantaged households have been disproportionately affected. For example, almost half of the informal workers in a survey said that they were eating less than before.

In this context, PDS can be all the more important to help vulnerable families tide over the pandemic-induced food insecurity.

As the pandemic spread through the country, the GoI announced the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana, providing 5 kgs of rice or wheat and 1 kg of pulses to eligible people free-of-cost, in addition to the regular entitlement of quota of foodgrains. The scheme was initially meant to be implemented from April 2020 to June 2020 but was later extended till November 2020. In April 2021, as the second wave of infections spread, the GoI again announced 5 kgs of free foodgrains per person per month for the months of May and June. This was further extended till November 2021.

But, as systemic issues such as the significant exclusion errors of eligible beneficiaries persist, vulnerable families are likely to struggle to cope with the economic effects of the pandemic.