MGNREGA: Women’s Participation and its Impact

26 August 2014

Launched in 2006, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) legally enshrines the “right to work” and ensures livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.

An important objective of MGNREGA has been to encourage women’s effective participation, both as workers and as administrators. For instance, according to MGNREGA guidelines, at least one-third of the beneficiaries shall be women who have registered and requested for work under the programme. Further, since employment is provided within 5 km radius of the village[1], it has the potential to bolster women’s participation. But how far has MGNREGA been successful in fulfilling this objective? This blog provides some insights into the implementation of the scheme in terms of providing equitable and easy access to work to rural women.

68th round of NSSO data shows that between 2004-05 and 2011-12, there has been a negative trend in women’s labour force participation rate (LFPR or the proportion of labour force to total population) in rural India. Rural female participation fell from nearly 25% in 2004-05 to 21% in 2009-10 and then even lower to around 17% in 2011-12. However, a study by Mehtabul Azam using nationally representative National Sample Surveys (NSS) data found that MGNREGA has helped mitigate the situation. The study exploited the phase-wise expansion of the MGNREGA[2] and found that the decline in labour force participation in MGNREGA districts has been lower than the decline observed in non-MGNREGA districts. This effect is found to be more pronounced in the case of female labour participation. Significantly, female share of works under MGNREGA is greater than their share of work in the casual wage labour market across all states[3]. Women are participating in the scheme much more actively than they participated in other forms of recorded work[4].

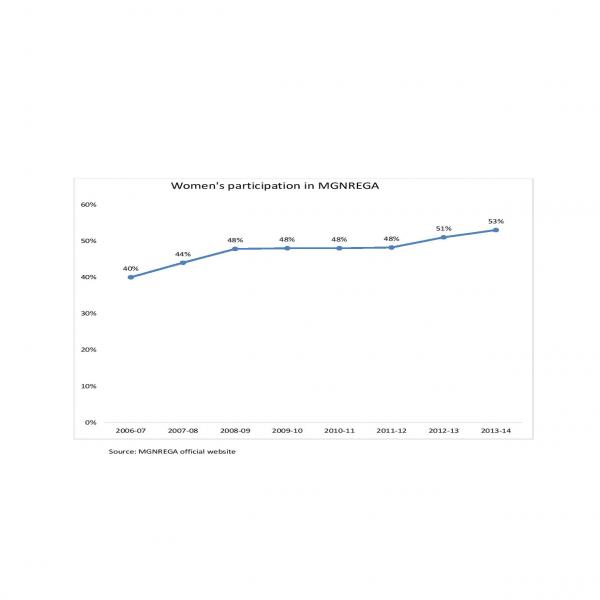

MGNREGA’s own official data shows that women’s participation in MGNREGA has been on the rise. At the national level, it increased from 40% in 2006-07 to 53% in 2013-14. However, there are wide variations across states and across districts within a state. While the statute mandates that at least one-third of the beneficiaries shall be women, the actual proportion varies, ranging from 22% in Uttar Pradesh to 93% in Kerala in 2013-14. The southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh show a higher rate of participation. Among the northern and some eastern states, however, the pattern has been low, with Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh being the exceptions.

The interstate variations in women participation can be attributed to a host of factors ranging from socio-cultural norms around female participation in labour force, mobility and intra household allocation of roles and responsibilities, opportunity costs in terms of wage differentials between private sector and MGNREGA, efficiency of implementing institutions at the State and local government levels and influence of Self-Help Groups and NGOs. For instance, in the case of Kerala, where MGNREGA has turned out to be an almost “ladies only” affair, the fact that Kudambashree (a State government initiative for poverty eradication through networking of women’s groups) has been placed in charge of its implementation has also made a striking difference to the level of women’s participation. This convergence has played its part in evolving the economic identity of the rural woman – as skilled labourer and farmer cultivator. It has also created a development interface for women to negotiate with local governments and power structures, giving new meaning to participatory governance. In Rajasthan, active youth groups and other social movements have been deeply involved and encouraged women participation in the programme. As a result, general levels of awareness are much higher than they would have been if advocacy had been left exclusively to the district administration. [5]

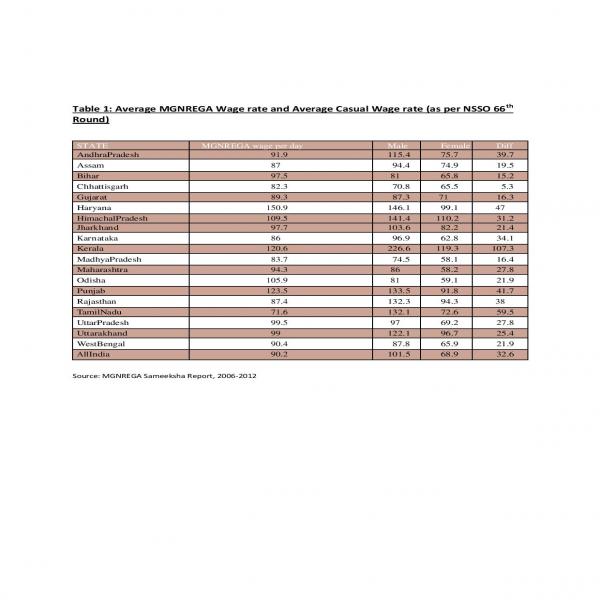

Under MGNREGA, the clause of equal pay for men and women has also been adhered to and has resulted in shaping out a better socio-economic scenario for rural women of India. NSSO 66th round data brings out the clear gender wage gap in unskilled wages (See Table 1 for more details).This difference was much larger in other public works; 98.3 per day for men and 86.1 per day for women. Such gender wage gaps are high across the country and among the highest in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The NSSO data shows that MGNREGA has reduced the traditional wage discrimination in public works. Women therefore, have looked upon MGNREGA, where minimum wages are to be paid, as a viable alternative. This may explain to an assured extent, the higher women participation in states where the initial condition in unskilled agriculture work is more imbalanced between men and women. An interesting example is that of Kerala which has the highest gender wage gap in agricultural labour and also the highest participation rate in MGNREGA. (93% female participation in MGNREGA).

Improved access to economic resources and paid work has had a positive impact on the socio-economic status of women. Studies[6] indicate that women exercise independence in collection and spending of MGNREGA wages, indicating greater decision-making power within the households. Women have also reported better access to credit and financial institutions. The mandatory transfer of wage payment through bank accounts has ensured a greater financial inclusion of women. Despite these improvements, certain factors such as non-availability of work-site facilities like crèches, long work hours, gender relations, implementation challenges continue to occlude women’s full participation. Functional and safe mobile crèche services, flexibility in terms of women’s working hours and provision for gender-specific life cycle needs are likely to provide women with more time and opportunity to participate actively in MGNREGA. This would be an important step in narrowing down the prevalent gender gap in rural India.

[1] In case, work is provided beyond 5 kms, extra wages of 10 percent are payable to meet additional transportation and living expenses.

[2] In February 2006, it was launched in 200 backward districts. An additional 130 districts were covered in 2007-08 in the second phase and the scheme went on to cover all districts in the third phase in 2008-09.

[3] Dutta, Murgai, Ravallion and Dominique, ‘Does India’s Employment Guarantee Scheme Guarantee Employment’.

[4] J. Ghosh, ‘Equity and Inclusion through Public Expenditure: The Potential of the NREGS’, New Delhi: Paper for International Conference on NREGA, 21–22 January 2009.

[5]Sudarshan, ‘India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act Women’s Participation and Impacts in Himachal Pradesh, Kerala and Rajasthan.

[6] C. Dheeraja and H. Rao. ‘Changing Gender Relations: A Study of MGNREGS across Different States’, Hyderabad: National Institute of Rural Development (NIRD), 2010.