Navigating the Subsidised Grain Delivery Labyrinth

2 May 2013

The Mid-Day Meal (MDM) Scheme, the world’s largest school-feeding programme,[1] guarantees a hot, cooked meal to each school-going child between the ages of 6 and 14 years in government elementary schools. Its main objectives are to increase enrolment, attendance and retention, while also improving the nutritional status of students. The scheme is beset with several problems in its implementation.[2]One of the most critical issues being that of delivery of quality grains to schools.We had recentlycarried out a qualitative study on the functioning of the MDMS scheme in a few districts. This blog highlights a number of issues we discovered which essentially stall the final delivery of grain to schools.

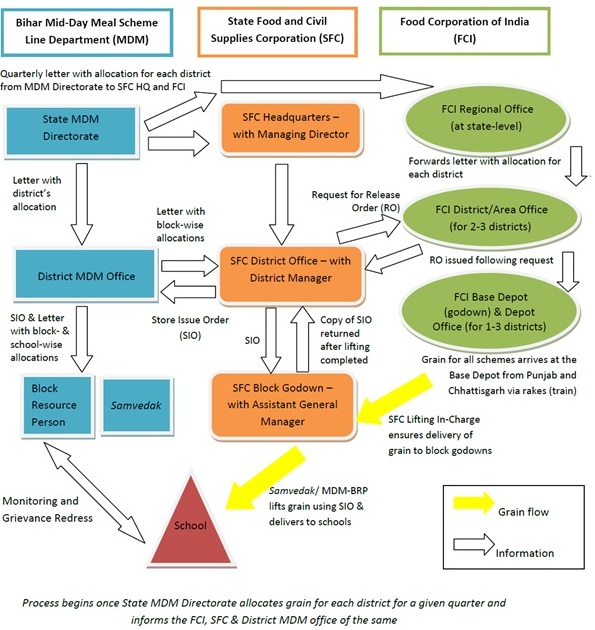

Before delving into these problems, it would be useful to briefly describe the process of lifting and delivering grain to schools. We will not describe here the complete process of allocating foodgrains to schools. Suffice it to say that the State MDM Directorate shares each district’s allocation with the District MDM Offices, State Food and Civil Supplies Corporation (SFC) and the FCI Regional Office (see flow-chart below). On the basis of these allocations,the FCI issues Release Orders (RO) to the SFC. These ROs allow the district to lift grain from the FCI base depot in the district. The SFC has to send its trucks to collect the grain from the FCI base depot. These trucks then deliver the grain to the SFC block godowns based on the allocations made by the district MDM authorities for each block. From the block godowns,the Samvedak (a contractor in charge of delivering the grain to the school) lifts the grain and delivers it onward to the school.Our findings reveal numerous bottlenecks responsible for delaying grain delivery at every step of this process.

Figure 1: Grain Flow & Organogram of Mid-Day Meal Scheme (State-level & below)

Bottlenecks at the FCI depot: Based on our interactions with the SFC District Manager, grain is not always available at the FCI base depot, due to delays in arrival from Punjab and Chhattisgarh, from where the grain is always procured. In one district during the second-half of financial year 2012-13, the FCI depot in the district headquartershad been shut down due to a pending investigation against the Depot In-Charge. So the district SFC had been reassigned to a depot in a neighbouring district. The new depot was already handling grains for three districts and, with the addition of one more, became greatly overburdened. Thus, the SFC trucks were not always able to lift the allocated amount of grain. Also, the surveyed district’s SFC had trouble transporting the grain back from the reassigned district as they were not allowed to take their own trucks to the new depot by the local truck unions. This was because the local unions demanded rangdaari tax (Protection tax) to allow the transport of grain. In another instance, the trucks which were sent to lift the grain were reassigned by an official of the new depotfor other work.

Bottlenecks at the Block godowns: To compensate for such delays, the SFC would unofficially make adjustments at the block godowns by using the grain for the Targeted Public Distribution Scheme (TPDS) for MDM. In the SFC’s parlance, this is known as “balance transfer,” or BT. While not an officially-advocated practice of the SFC or FCI, this form of “adjustment” of grain is common-place in the surveyed district.In addition, there is often pressure on the block godownsfrom PDS dealers to allow them to take the MDM grain. According to one of the Samvedaks we spoke to, the Assistant General Manager (AGM) at the block godowndoes not always inform them when the MDM grain has arrived,thereby allowing the PDS dealers to take the grain. While one AGM we spoke to, denied any practice of this sort, the Samvedaktold us that he has to keep in touch with some local people near the godown who inform him about grain arrival. A couple of times, the Samvedakreached the godown and found the MDM grain being taken by the PDS dealers. In suchcases, the Samvedak has to call the SFC district manager, who then instructs the AGM to correct the situation. Resolving this matter usually takes a long timeand the Samvedak is unable to deliver the grain to the schools on that day. The severe lack of manpower in the SFC further complicates matters. Currently, there are ten block godowns which supply grain for MDM, each of which is required to have an AGM; however, there are only three officials in charge of all ten.Despite having a schedule of days when each godown would be open, the lack of adequate human resources makes it harder for the AGMs to open the godowns as scheduled and manage the grain lifting.The Samvedak receives a Store Issue Order (SIO) from the SFC, which allows him to lift grain from the block godowns. There have been a few instances where the Samvedak has reached the block godowns with the SIO but the grain has not been available at the godown. Technically, the SIO is not supposed to be drawn unless there is grain available at the block godowns.Thus, along with the delay, the Samvedak also incurs a large cost here as he has to pay for the trucks he has taken on rent. The labour at the godowns also charge high amounts for loading the grain onto the Samvedak’s trucks, as they are not paid by the SFC for loading grain to the clients such as samvedaks or PDS dealers. The Samvedak has tried bringing his own labourers but the local labourers did not allow them to enter. Despite repeated complaints to the MDM authorities, the problems with the labour union have not been resolved as the MDM authorities have no power over the labour union. The MDM authorities have also complained to the SFC District Manager and to the District Magistrate, to no avail.

Finally, the fact that block godowns open late in the day (around 11am-12pm, according to MDM authorities and Samvedak) poses problems for Samvedaks, who are not only required to deliver the grain on the same day that they lift it, but to also inform the district MDM authorities and the MDM Directorate in Patna of the same. The SFC district administration and AGMs, however, claim that the godowns are open by 10:30am and that it is the Samvedaks who arrive late to lift grain.

Bottlenecks in final delivery to schools: Delays in lifting grain from the godown on a given day imply thatthe Samvedak is often forced to deliver them to schools late into the evening. He usually requests the teachers to stay in their schools on such a day; however, some teachers leave before the grain arrives and thus the Samvedak is forced to either take back the grain or leave it at a neighbouring school. The Samvedak also said that it is difficult to deliver grains to schools in the interior areas as the trucks and tractors cannot reach these places. Thus, local labour is required to carry the grain and they demand a high price. During the monsoon season, this problem is further exacerbated.

These were some of the issues that came up in our qualitative analysis of the grain delivery process in one of the states we studied. We can see that even after the RO has been issued, there are a number of stages that the grain goes through before finally reaching the school, and each stage has its set of bottlenecks which can delay the delivery of grains to the schools.Considering the crucial role the FCI and the SFC play in the provision of MDM, it is important to delineate accountability structures such that the schemes are not adversely affected. In the current MDM set-up, we find that the MDM department has no authority to question delays on the part of the SFC or the FCI. Similarly, the Samvedak, who has been contracted by the MDM department, has to resort to contacting the SFC District Manager in case of problems. Since there are two separate entities working together, the problems can take longer to resolve. The roles and linkages between these two entities need to be thought out more carefully so as to minimise the scope for problems.To this end, strengthening the channels of information-sharing and communication between all the stakeholders (FCI, SFC, the MDM department and schools) is imperative. Developing the capacities of district- and block-level Steering-cum-Monitoring Committees to hold each actor responsible at their own levels would alsobe a vital step in closing the accountability gap.

[1]Khera, R., 2006, “Mid-Day Meals in Primary Schools: Achievements and Challenges,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 46 (Nov. 18-24, 2006), pp. 4742-4750.

[2]For instance, see the following: 1. De, A. et al., 2010, PROBE Revisited: A report on elementary education in India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2. Drèze, J. and A. Goyal, 2003, “Future of Mid Day Meals,” Economic and Political Weekly; Vol. 38, No. 44, pp. 4673-4683. And 3. Singh, A., A. Park, and S. Dercon (2012), “School Meals as a Safety Net: An Evaluation of the Mid-Day Meal Scheme in India,” Working Paper No. 75, Young Lives, Oxford, UK: University of Oxford.