This blog is part of a series on policy decisions, the causes and consquences of the Kerala floods. The first blog can be found here.

They say that what is true of Kerala is generally not true of other states. That is not only true of its long standing position in the forefront of states with higher education and health indicators, but also of its spread out habitation patterns. For decades now, barring city states like Delhi, Kerala has had the highest density of people per square kilometre. The statement that Kerala is an urban-rural continuum is now made so routinely that it is a cliché. However, that is also not a recent phenomenon; Kerala’s spread out habitation patterns have been a feature of the past too.

Take my own ancestral village in Mankurussi village, Mankara Panchayat, Palakkad district. Here, not very far from the dense jungles of the Western Ghats, are the rich rice fields of Palakkad. The soil, contrary to popular notion, is not very rich in nutrients. Much of the clay and alluvium has been washed down from the low tumbling laterite hills into shallow valleys, now long since tended and moulded into paddy fields. The homes are crouched on these laterite hills; they may be as many or as few, depending upon the availability of water. Behind each such home there is usually a small, almost natural forest, known as a Thodiga. The trees vary in a Thodiga from the Palmyra to the locally known Kazhani, a twisted thorny tree that has excellent timber, to a few teak trees and the ubiquitous Jack and wild Mango. Thodigas act as water sinks, break the fall of the heavy rain, and soak it in like a sponge. They provide plenty for the family’s needs, from an occasional tree cut down for rafters and reapers for roofs – even the fibrous Palmyra transforms to dense timber over the years – to Jack and Mango fruit, mushrooms, Chena (amorphophallus yam) and Chembu (knows as Arbi in Hindi) and plenty of vines and shrubs useful for various Ayurvedic medicines.

To visit each home in Mankurussi, is not an easy task of just walking down a main street and a few side lanes. The old houses in Mankurussi dot the laterite hills and the village roads twists and turns through the Thodigas to reach them. There are people always on the roads, but one does not necessarily see their houses, tucked away as they are behind each home’s forest. And so, Mankurussi meanders into the next village and the next.

Back in the mid 1880s, when the British built their strategically important railway line linking Madras to Mangalore, the line dipped southward to Coimbatore and then went westward through the Palghat Gap, a 30 kilometre wide breach in the Western Ghats that provided the easiest entry to the west coast. The survey of the line went directly through the low laterite mound on which my forebears had built their mud and thatch naalukettu house; one with four sides and a courtyard enveloped within. My great grandfather, displaced from his home, built his next home on a hill not far away. The laterite was chipped away and a mud foundation rammed in. The walls were made of mud too, mixed with several ingredients, an art long lost to the world now, to provide an enormously strong structure that went up two floors. The earlier thatch was replaced with the more upmarket tiles in more prosperous times.

Over time, the homes in Mankurussi have become more modern. The old homes remain, but in their compounds are built new concrete boxes, brightly painted. Worse, in violation of the law that prohibits the conversion of low lying paddy land into other uses, homes have been built in them as well. The thodigas are now converted into more ‘useful’ spaces; these jungles have been replaced by rubber and coconut plantations. They are not quite the same thing; no leaf mold carpets the jungle floor.

With each such step, of replacing old ways with the new, the people of Kerala have become more vulnerable. Floods could inundate the houses in paddy lands, but what’s more, rubber and coconut plantations have not a fraction of the water absorbing quality of the thodigas they replaced.

When the rains hit Palakkad district last month, the Malampuzha dam was opened like the rest of the dams in Kerala, and water breached the banks of the Bharatapuzha River. The rain poured for several days, and water entered many modern concrete and steel homes. Those who built their homes in paddy fields were especially hard hit, as the flood waters rose. Yet, my grandfather’s hundred and thirty year old mud house, built without as much as a kilo of steel or cement stood impassively against the rain, with no damage at all.

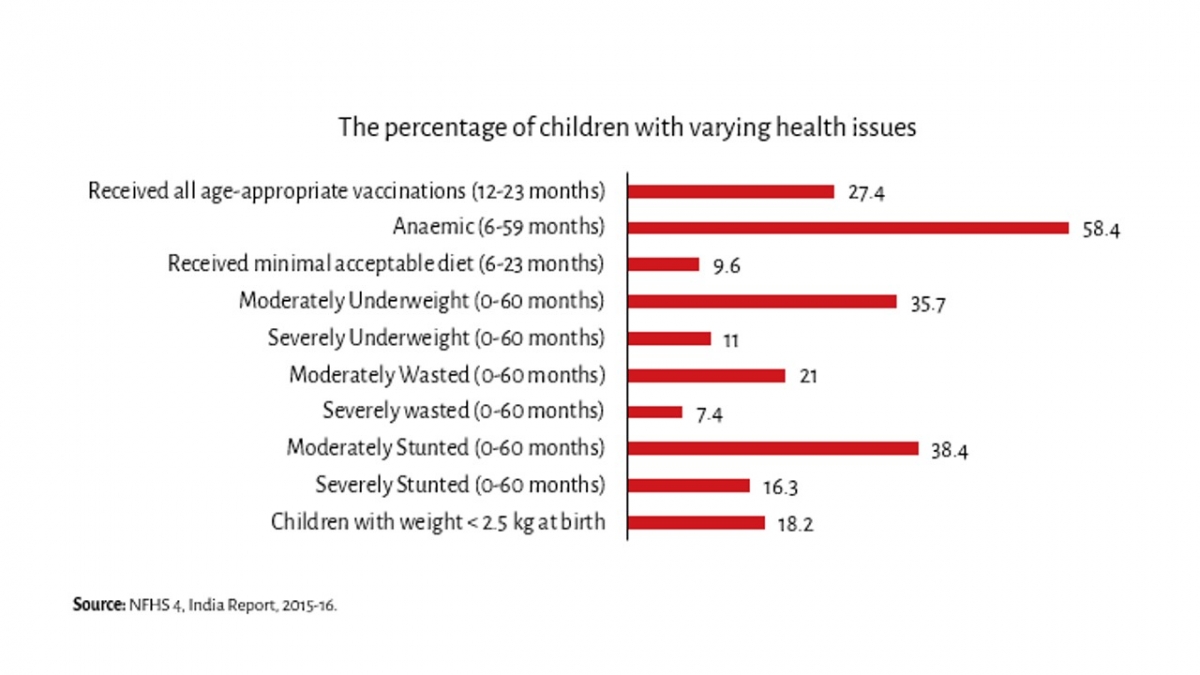

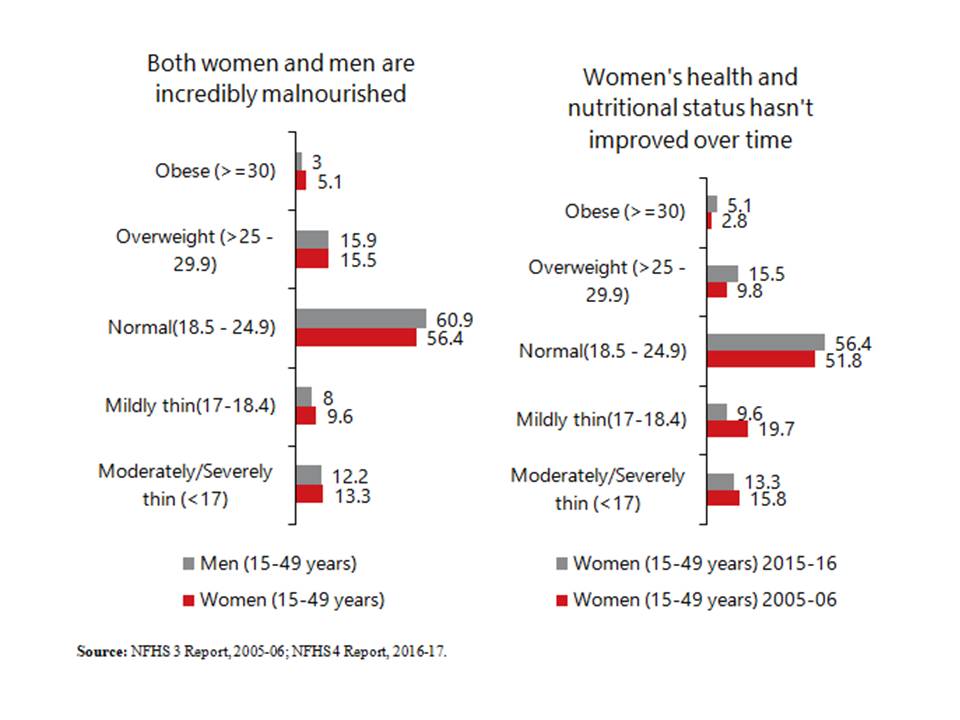

adverse maternal outcomes and health risks for unborn children. This has likely contributed to the consistently demoralising state of child health in India. Therefore, while undernourishment has always been a problem, over-nourishment is rapidly emerging as source of alarm.

adverse maternal outcomes and health risks for unborn children. This has likely contributed to the consistently demoralising state of child health in India. Therefore, while undernourishment has always been a problem, over-nourishment is rapidly emerging as source of alarm.