Original article was published in Huffington Post India available here.

1 फरवरी 2017 को वित्त मंत्री ने अपनी सरकार का चौथा बजट पेश किया। हर वर्ष की भांति इस वर्ष भी बजट भाषण के बाद राजनीतिक दलों और टिप्पणीकारों ने बजट में घोषित प्राथमिकताओं और आवंटनों पर खूब तर्क-वितर्क किया। खासकर सामाजिक क्षेत्र की योजनाओं के लिए आवंटन पर सबसे तीखी बहस हुई क्योंकि राजनेताओं और टिप्पणीकारों के लिए इस बात पर सहमत होना बड़ा मुश्किल है कि इस क्षेत्र के लिए आवंटित राशि बहुत कम है या बहुत ज़्यादा। लेकिन किसी सामान्य नौकरशाह और सामाजिक क्षेत्र की इन योजनाओं की वास्तविक लाभार्थी आम जनता के लिए बजट अनुमानों पर होने वाले ये बहस-मुबाहिसे बेमानी हैं।

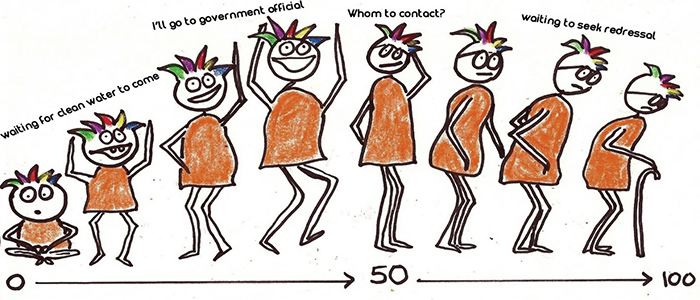

सच तो यह है कि आवंटित राशि को नौकरशाही के विभिन्न स्तरों के जरिये तेजी से और कुशलतापूर्वक लाभार्थियों तक पहुंचा पाना भारत सरकार के लिए बेहद कठिन रहा है। नतीजा यह होता है कि स्थानीय प्रशासन और नागरिकों के पास कोई गारंटी नहीं होती कि इन बजट आवंटनों में से कितनी राशि उन तक पहुंचेगी और कब तक पहुंचेगी। अधिकतर पाठकों को यह जानकार हैरानी होगी कि बजट-घोषणा के दो वर्ष बाद जब पूरी जानकारी मिलती है तो पता चलता है कि सरकार द्वारा व्यय की गयी राशि प्राय: बजट के वास्तविक अनुमानों से बेहद कम थी। ऐसा होने की एक महत्वपूर्ण वजह है निधियों के प्रवाह की धीमी गति। स्थिति तब और खराब होती है जब पैसा स्थानीय स्तर तक इस तरह पहुंचता है कि उसे स्थानीय जरूरतों और प्राथमिकताओं पर खर्च करना मुश्किल हो जाता है।

व्यय तंत्र की ये कमियाँ विशेषकर इसलिए भी गंभीर हैं क्योंकि कागजों पर भारतीय राज्य बेहद सहभागितापूर्ण है। महज यह सुनिश्चित करने के लिए कि सरकारी व्यय जरूरतों और प्राथमिकताओं के मुताबिक हो, नागरिकों को नियमित तौर पर सरकारी कार्यक्रमों में भागीदारी करने, उनकी निगरानी और ऑडिट करने के लिए आमंत्रित किया जाता है। मसलन, 73वें और 74वें संवैधानिक संशोधनों के द्वारा स्थानीय प्रशासन को योजनाएँ बनाने का अधिकार देकर और लोगों की सीधी भागीदारी सुनिश्चित कर शक्तियों के विकेन्द्रीकरण द्वारा सहभागिता को संस्थागत रूप दिया गया। इसके अलावा, सामाजिक क्षेत्र की हर योजना के तहत ऐसी समितियां बनाना ज़रूरी है जिनके जरिये नागरिक योजना निर्माण और सरकार की निगरानी में भागीदारी कर सकें। लेकिन वास्तविकता काफी अलग है।

आइये समझते हैं, कैसे। विकास के एजेंडे के महत्वपूर्ण घटकों की ज़िम्मेदारी स्थानीय सरकारों को सौंपने के बाद, उन्हें अधिकारों का वास्तविक अंतरण न हो, इसके लिए राज्य और केंद्र की सरकारों ने हर मुमकिन कोशिश की है। अधिकांश विकास गतिविधियों के लिए आवंटित राशि स्थानीय निकायों की बजाय समानान्तर संस्थाओं को अंतरित की जाती है। परिणामस्वरूप स्थानीय प्रशासन में कई संस्थाएं हो जाती हैं, और जिम्मेदारियों में दोहराव होता है। उदाहरण के लिए, एकाउंटेबिलिटी इनिशिएटिव के एक ताजा अध्ययन के मुताबिक कर्नाटक में, 2014-15 के बजट का 11 प्रतिशत अंश, जो पंचायतों को आवंटित किया जाना था, राज्य के प्रशासनिक विभागों को आवंटित किया गया। साथ ही, जो राशि पंचायतों को आवंटित की भी गयी, उसमें से 23 प्रतिशत राशि सरकारी कर्मचारियों के वेतन के लिए थी। लेकिन पंचायतों का इन कर्मचारियों पर कोई प्रशासनिक नियंत्रण नहीं होता, और ज़्यादातर की नियुक्ति राज्य का सरकारी तंत्र करता है। इस वजह से पंचायतों को आवंटित राशि पर उनकी स्वायत्ता बेहद सीमित हो जाती है।

जमीनी स्तर पर, पंचायत वित्त के संबंध में राज्य के एक ज़िले में किए गए हमारे एक सर्वेक्षण से पता चला कि किसी ग्राम पंचायत के राजनीतिक क्षेत्राधिकार में खर्च होने वाले कुल 6 करोड़ रुपयों में से ग्राम पंचायत महज 3 प्रतिशत यानी 20 लाख रुपये ही अपनी मर्ज़ी से खर्च कर सकती है! इससे न केवल ग्राम पंचायतों द्वारा स्थानीय स्तर पर किए जाने वाले योजननिर्माण का कोई अर्थ नहीं रह जाता- आखिरकार जब अपने इलाके में होने वाले ज़्यादातर खर्च पर आपका कोई नियंत्रण ही नहीं है तो आप योजना कैसे बनाएँगे; – बल्कि इससे निधियों के प्रवाह की निगरानी भी असंभव हो जाती है। क्योंकि किसी ग्राम पंचायत में कितनी राशि आती है, इसकी जानकारी के लिए आपको गाँव की हर सरकारी संस्था और गाँव में चलने वाले हर सरकारी कार्यक्रम के लिए बजट आवंटन और व्यय के लेखे-जोखे का पता राज्य सरकार तक लगाना होगा। और यह देखते हुए कि हर योजना का रिपोर्टिंग और वित्त प्रबंधन का तंत्र अलग है, यह एक नामुमकिन काम हो जाता है। सार्वजनिक वित्त की निगरानी करने वाले हमारे अनुभवी लोगों की टीम को भी इन आकलनों तक पहुँचने में डेढ़ वर्ष लगा! ऐसे मामलों में सूचना का अधिकार जैसे उपाय भी काम नहीं करते क्योंकि सरकार के पास ऐसा कोई तंत्र ही नहीं है जो किसी पंचायत के सम्पूर्ण राजनीतिक क्षेत्राधिकार में आने वाले व्यय आंकड़ों को इकट्ठा कर सके – कितना ही सदाशय सूचना अधिकारी हो, उसके लिए यह सूचना उपलब्ध कराना कठिन है।

राज्य सरकारों और केंद्र सरकार द्वारा चलायी जाने वाली योजनाओं का हाल भी कुछ अलग नहीं है। शिक्षा क्षेत्र को लीजिये। स्थानीय भागीदारी के सिद्धांतों के अनुसार, केंद्र सरकार की प्रमुख योजना सर्व शिक्षा अभियान के तहत अपेक्षित है कि बजट निर्माण स्कूल की योजनाओं के मुताबिक हो। ये योजनाएँ ज़िला प्रशासन और राज्य सरकारों से होते हुए अंत में भारत सरकार के मानव संसाधन विकास मंत्रालय के पास अनुमोदन के लिए पहुँचती हैं।

लेकिन जैसा कि एकाउंटेबिलिटी इनिशिएटिव के अध्ययनों से पता चलता है वास्तव में योजना निर्माण बेहद अलग ढंग से होता है। सर्व शिक्षा अभियान का बजट बेहद केंद्रीकृत है। स्कूल, कुल शिक्षा बजट का 1 प्रतिशत से भी कम अपने विवेक से खर्च कर सकते हैं, ऐसे में योजना और बजट निर्माण में स्कूलों की योजनाओं का कोई महत्व नहीं रह जाता। ज़िला प्रशासन वार्षिक योजनाएं बनाते हैं। लेकिन ऐसा करते समय उनके पास महत्वपूर्ण जानकारियाँ, जैसे किसी वर्ष में उपलब्ध संसाधनों की जानकारी नहीं होती। परिणामस्वरूप, ज़िला प्रशासन की योजनाएँ इच्छाओं की फेहरिस्त भर रह जाती हैं और अंत में जो बजट अनुमोदित होता है, उसका ज़िला योजनाओं से बहुत कम लेना-देना रह जाता है। जैसे, 2012-13 की ज़िला योजनाओं के हमारे विश्लेषण से पता चला कि बिहार के नालंदा ज़िले हेतु प्रस्तावित बजट का सिर्फ 59 प्रतिशत ही अनुमोदित हुआ। इसी प्रकार, 2011-12 में हिमाचल प्रदेश के कांगड़ा ज़िले द्वारा प्रस्तावित बजट का 79 प्रतिशत ही अनुमोदित हुआ। राज्यों को भी यह समस्या झेलनी पड़ती है और प्राय: अंतिम अनुमोदित बजट केंद्र सरकार द्वारा निर्धारित प्राथमिकताओं के मुताबिक ही होता है। नतीजतन ऐसा बजट बनता है जिसका स्थानीय जरूरतों और प्राथमिकताओं से बहत कम लेना-देना होता है। इस परिदृश्य में, स्थानीय प्रशासन की कार्य संस्कृति ऐसी हो जाती है कि वे निर्देशों का इंतज़ार करते रहते हैं, और जैसा कि एक कर्मचारी ने कहा, “आरामदायक परिस्थितियों में पूरा आराम करते हैं”।

कमजोर सार्वजनिक वित्त प्रबंधन तंत्र समस्या में और इजाफा करता है। मौजूदा व्यय प्रबंधन तंत्र का प्रारूप आदेशों की पदानुक्रमिक श्रृंखला द्वारा वितरण पर आधारित है। जहां प्रत्येक व्यय प्राधिकारी के पास अपने से अगले स्तर को धनराशि की एकमुश्त किस्तें जारी करने का अधिकार होता है। इन किस्तों को जारी किए जाने के लिए, प्राधिकार और मंजूरी के कई स्तर होते हैं। किसी भी एक स्तर पर देरी का असर पूरे तंत्र पर पड़ता है और ज़्यादातर ऐसा होता है कि योजनाएँ और बजट अनुमोदित होने के बावजूद भी निधियाँ शायद ही कभी समय पर आगे पहुँचती हों। उत्तर प्रदेश में राष्ट्रीय स्वास्थ्य मिशन के संबंध में किए गए एक हालिया अध्ययन में एकाउंटेबिलिटी इनिशिएटिव के शोधकर्ताओं ने पाया कि नवंबर 2014 तक राज्य के कुल वार्षिक बजट बजट का महज 10 प्रतिशत ही जारी किया गया था। चूंकि वित्त वर्ष मार्च में समाप्त होता है, इसलिए धनराशि देर से जारी होने का परिणाम होता है आखिरी समय में किसी भी तरह पैसा खर्च करने की हड़बड़ी। चार जिलों में व्यय के विश्लेषण से हमें पता चला कि कुल वार्षिक बजट का 56 प्रतिशत जनवरी से मार्च के बीच खर्च किया गया।

शिक्षा क्षेत्र की स्थिति भी ज़्यादा अच्छी नहीं है। जैसा कि हमने भारत के 50 प्रतिशत से अधिक स्कूलों के अपने सर्वेक्षण में पाया कि ज़रूरी खरीद के लिए स्कूलों को जो छोटे-मोटे वार्षिक अनुदान मिलते हैं, वे भी स्कूल के बैंक खातों में नवंबर-दिसंबर तक पहुँचते हैं – तब तक स्कूल का सत्र आधे से ज़्यादा बीत चुका होता है।

इस देरी से भारत को बहुत नुकसान उठाना पड़ता है। निधियों के इस धीमे प्रवाह का नतीजा होता है कम व्यय। खर्च न किया गया यह पैसा बैंकों में पड़ा रहता है – डॉ॰ संतोष मैथ्यू के एक आकलन के मुताबिक विभिन्न स्तरों पर विकास निधियों का लगभग एक लाख करोड़ रुपया बैंकों में जमा रहता है, बैंक उस पर ब्याज कमाते है, लेकिन देश के लिए उसका कोई उपयोग नहीं हो पाता।

इससे भी दुखद यह है कि जब वित्त वर्ष के अंत में आवंटित राशि पहुँचती है तो वित्त-वर्ष की समाप्ति से पहले उसे खर्च करने और कागजी कार्रवाई पूरी करने का बड़ा दबाव रहता है। इसकी वजह से ऐसी अफरा-तफरी होती है कि व्यय का जमीनी जरूरत से कोई संबंध नहीं रह जाता। गत वर्षों में, हमें ऐसे उद्यमी प्रधानाध्यापक मिले हैं जिन्होंने आवंटित राशि का उपयोग करने के लिए बिना भवन वाले स्कूल के लिए अग्निशमन यंत्र खरीद लिए; मेज कुर्सियों के होते हुए और मेज कुर्सियां खरीदीं, साफ़सुथरी दीवारों पर फिर से पुताई करवाई ताकि लेखापरीक्षकों के निरीक्षण के समय और अगले साल की किस्त जारी होने के लिए उनके उपयोग प्रमाणपत्र तैयार हों।

दुखद वास्तविकता यह है कि यह समस्या सर्वविदित है और इसका समाधान भी मौजूद है। निधियों के त्वरित प्रवाह की व्यवस्था वाले व्यय तंत्र को विकसित करने के लिए आसानी से प्रौद्यिगिकी की मदद ली जा सकती है। इस बारे में कई समितियां बनी हैं, जिनमें नवीनतम है 2011 में नन्दन नीलकेणी की अध्यक्षता में बना प्रौद्यिगिकी सलाहकार समूह जिसने निधियों के प्रवाह के लिए व्यय सूचना तंत्र बनाने की सिफ़ारिश की थी। लेकिन इनमें से किसी भी समिति की रिपोर्ट से जमीनी स्तर पर कोई बदलाव नहीं आया है।

विमुद्रीकरण (नोटबंदी) के जरिये प्रधानमंत्री मोदी ने जनता में अपनी भ्रष्टाचार विरोधी छवि को और मजबूत बनाने का प्रयास किया है। लेकिन अगर वे वास्तव में उस भ्रष्टाचार को खत्म करना चाहते हैं जिसका अधिसंख्य भारतीय अपने रोज़मर्रा के जीवन में सामना करते हैं तो शुरुआत यह सुनिश्चित करने से होनी चाहिए कि सरकारी पैसा सही जगह और सही व्यक्ति तक, पारदर्शी ढंग से और समय पर पहुंचे। उपाय मौजूद हैं-बस उन्हें लागू करने की देर है।