‘Pulling’ Mobile Governance into the Mainstream

24 July 2020

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman launched the PM eVidya online and mobile education platform in May 2020. This represents yet another step towards embracing ICT for governance in India. However, citizen engagement with ICT-based services has tended to be low.

Shortfall of engagement with Mobile governance (m-governance) can arise from designing initiatives without sufficiently taking into account factors that foster user demand, such as an awareness of, and acceptance and recognition of benefits by potential users. Other key issues influencing m-governance access and usage have been – infrastructure challenges, regulatory frameworks and multiplicity of overlapping services.

M-governance utilises mobile technology – SMS, apps, Interactive Voice Response Systems (IVRS), geo-location and others – to improve access to public service delivery, and enhance accountability and citizen participation in policy-making and execution. Globally, the ubiquity of mobile phones has been channelled towards enhancing supply and efficacy of government services across policy domains – from opening up telemedicine, to reporting corruption [1] [2].

In India, government actors have been capitalising on the rapid rise in mobile penetration and internet service provision. India now possesses a tremendous user base of wireless and mobile telecom subscribers, with almost half located in rural areas [3]. The government introduced Mobile Seva, a country-wide initiative in 2011 to facilitate central, state and local governments extending a variety of mobile services.

Catering to over 3,500 government departments, Mobile Seva presently offers 944 mobile apps in domains that include healthcare, agriculture, sanitation and education. Collectively, these have seen over 81 million downloads so far [4]. Other m-governance initiatives include: the Aarogya Setu (tracking COVID-19 exposure and vulnerability), eNAM (connecting farmers and traders with agri-markets) and SDMC 311 (South Delhi Municipal Corporation’s flagship service) apps.

Despite these seemingly impressive statistics, m-governance is not a routine feature of government-citizen interaction in India. For instance, a closer look at the services offered on the Mobile Seva app store shows that downloads usually range to a few thousand, with active usage likely to be lower.

Why do citizens in India not take advantage of the m-governance drive more often?

Given that usage statistics [5] are unavailable, app downloads can serve as a proxy indicator for user awareness and uptake. The average number of downloads per app from Mobile Seva is presently around 86,000. The download count for MyGov – the Centre’s flagship participatory governance platform, launched in 2014 – exceeds 1 million. Contrast this with the recent uptake of Aarogya Setu, which already has over 100 million downloads and is a mandated download. These aspects underscore the significance of responsiveness to demand.

Experience from other countries suggests that this is not just an Indian phenomenon – in general, e-governance initiatives suffer from short-lived successes followed by a dearth of scalable and sustainable engagement. Lack of citizen awareness has been cited as a factor that can diminish the potential of the m-governance programme in India too [6].

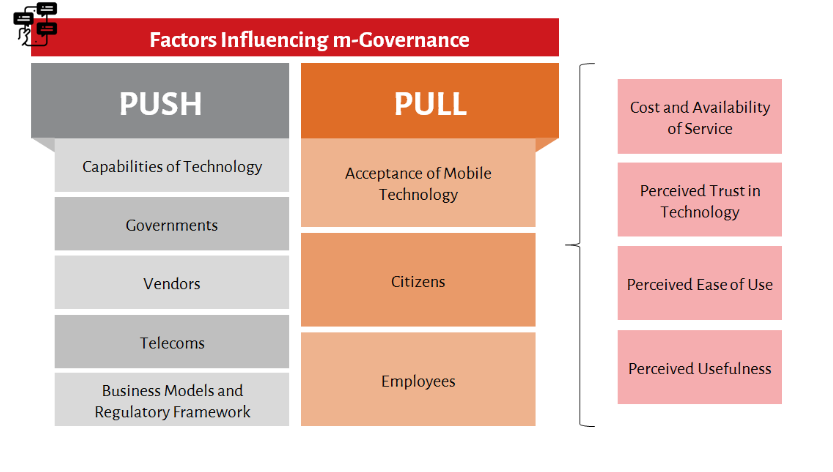

Delving deeper, m-governance uptake can broadly be influenced by ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors [7], as outlined in Figure 1 below. Push factors create an enabling environment and foster m-governance service provision. These include the level of technological and infrastructure development in a country, the role of governments and telecoms, business models, and legal frameworks. For instance, engendering access to mobile phones, internet and electricity facilitates the supply of m-governance services – hence, these qualify as push factors.

Concurrently, pull factors influence demand and adoption of m-governance services. These are centered on individuals – particularly, citizens and government functionaries – who need to be informed of these services. They should be able to access them easily and cheaply, possess the necessary skills for usage and perceive advantages. An example is the prevalence of mobile literacy as it would enable potential users to pull into usage the services on offer.

Acceptance and mainstreaming of m-governance relies not just on the availability of these services but also on overcoming pull-side deficiencies that affect user demand and acceptance.

Figure 1: Push and Pull Factors of m-Governance

Source: Framework adapted from Carroll (2006) [7] and Almarashdeh & Alsmadi (2017) [8]

The lack of knowledge and infrequent use of m-governance suggests that, in line with global experience, India too has overemphasised activating the push side of the equation. This includes leveraging mobile technology, setting up infrastructure and making m-governance services available – without understanding or strengthening user demand.

To overcome this, focus should shift to developing services wherein citizens can readily recognise value of using such services, and that simplify and foster greater engagement with governments. Improving awareness of m-governance initiatives and digital literacy are also crucial.

Thus, while not discounting their significance, the government would benefit from moving beyond its focus on infrastructure and supply-side issues to adopting a more demand and user-centric approach. This will help move closer to a ‘Digital India’ and prevent m-governance from becoming just another buzzword in the policy-making landscape.

References:

[1] Hellström, J. (2009). ““Mobile phones for Good Governance: Challenges and Way Forward”. Retrieved via URL on 20 June 2020: <https://www.w3.org/2008/10/MW4D_WS/papers/hellstrom_gov.pdf>

[2] Kanyam, D. et al. (2017). “The Mobile Phone Revolution: Have Mobile Phones and the Internet Reduced Corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa?”. World Development, Vol. 20.

[3] inc42 (2019). “Is India Reaching The Saturation Point For New Mobile Subscribers?”. Retrieved via URL on 20 June 2020: <https://inc42.com/features/has-india-reached-a-ceiling-point-of-new-mobile-users/#:~:text=With%20rampant%20onboarding%20on%20new,between%201.3%20and%201.4%20Bn.>

[4] Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. Mobile Seva website, retrieved via URL on 20 June 2020: <https://mgov.gov.in/>

[5] Daily Active Users or 1-Day Active Users – the number of unique users who initiated activity on a website or mobile app – is a metric used to track the level of engagement with an online service. For instance, see URL: <https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/6171863?hl=en>

[6] Kumar, R. (2016). “Enhancing the Reach of Public Services through Mobile Governance: Sustainability of the Mobile Seva Initiative in India”. Electronic Government, Vol. 12, No. 2.

[7] Carroll, J. (2006). “‘What’s in It for Me?’: Taking M-Government to the People”. Retrieved via URL on 20 June 2020: <https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=bled2006>

[8] Almarashdeh, I. & Alsmadi, M. (2017). “How to make them use it? Citizens’ Acceptance of M-government”. Applied Computing and Informatics, Vol. 13, Issue 2.

Udit is a Senior Research Associate at Accountability Initiative.

Also Read: Sustainability and Accountability Issues of Common Service Centres