Safeguards Needed in the Face of Inevitable Urbanisation

1 October 2018

This blog is part of a series on policy decisions, the causes and consquences of the Kerala floods. The first blog can be found here.

Kerala is caught in a bind where its urbanisation has led to a continuous and thickly populated settlement pattern, but there is little safe land left for more habitation development. The 2016 report of the State’s Working Group on Urban Issues highlights this problem, in the following words:

“Kerala also needs to focus on what is internationally gathering momentum – the goal of sustainable urbanisation – which is to now seen to be central to strategies for mitigating climate change. Economising on emissions and promoting energy efficiency in urban areas has much to do with how cities are spatially configured and serviced. Apart from local land use regulation that steer settlements away from disaster prone areas and sensitive ecosystems, building compact cities around public transport and pedestrian movement constitute measures that can considerably improve energy efficiency of cities, reducing their climate change impact.”

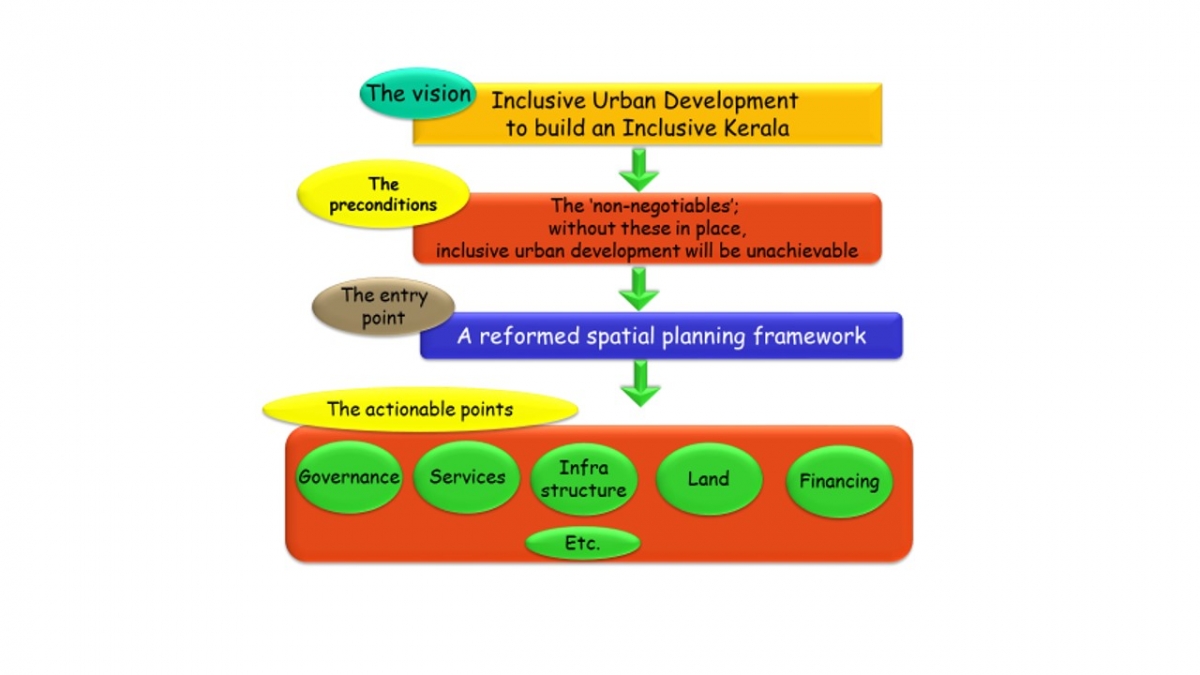

Keeping this overarching vision in mind, the report goes on to lay down its approach, as follows:

To derive appropriate policy to ensure the achievement of the vision of inclusive urban development, the report goes on to lay down five non-negotiable principles that aim to make urbanisation sustainable.

The first, the report says, is to realise that the carrying capacity of urban areas is not infinite, but is limited by environmental constraints and conservation of natural and heritage resources. When one considers lands that cannot be diverted, such as the Coastal Restricted Zone and paddy fields, or heritage zones that cannot be taken up for inner city redevelopment, then the land that is open to green-field development gets considerably limited. This calls for tough choices, where preservation of the natural or existing built environment that is part of the State’s invaluable cultural heritage.

The second, according to the report, is that everything that has the effect of making our cities safe to live in should be done and anything that has the potential to make our cities unsafe in any fashion whatsoever, should not be rationalised or attempted to be done. Safety is a wide ranging idea and can include issues that touch the city as a whole (for example, where landfills should be located or whether reclamation of land from lakes should be attempted) to those that are very local in their span of influence (such as location of streetlights or public lighting in parks, or police stations and frequency of police beats). Furthermore, the components of a safe environment and therefore, the prioritisation of their implementation, can radically differ from stakeholder to stakeholder. What a child, a senior citizen, a differently abled person, a woman or a migrant labourer wants might vary dramatically from the priorities of an average citizen. For example, while mobility affects everyone, women and men often have substantially different patterns of demand for transport services. Personal safety is a major concern for working women who commute after dark and this often limits the choice and locations of their work. Therefore, planning for better law and order and safety should take precedence over other priorities in planning.

Third, the participatory process in planning and implementation cannot be bypassed. In Kerala’s context of decentralized planning with peoples’ participation, it is essential to have the active involvement of people as stakeholders from the very beginning of Plan formulation stage. While Grama Sabhas in rural areas have a high degree of participation from women, particular care will need to be taken to ensure the meaningful participation of children, the elderly, and the differently abled in participatory processes. Instruments of participation may need to be differently configured, in order to take care of the diverse nature of urban stakeholders and the fact that unlike the rural counterpart, the interest in urban services is not confined to that available near the residence of the stakeholder concerned.

Fourth, considerations of departmental turf should not become a constraint in achieving coordination. The government should not be swayed by vested interests whilst attempting the departmental redesign to streamline processes and improve coordination. Departments that are redundant or inappropriate in their current form, should be reformed or even done away with, if necessary. Institutions blaming the other for failure to achieve the common objective should be avoided.

Fifth, the concept of users paying for the services enjoyed and the polluter paying for the pollution caused, should be enforced. Wherever affordability is an issue, targeted transparent and measurable subsidies should be provided for the disadvantaged, marginalised and poor across all segments of growth.

I shall highlight what the report suggests, should be the spatial approach to local planning, in my next blog.

The previous blog in the series is here.