The Changing Shape of India’s Health Crisis

1 August 2018

How far has India progressed on securing welfare of all? This blog is part of a series which uses data to unpack the status of health, education and policy reforms in India’s 71st year of freedom.

There has been sea change in the kind of diseases that are making people in India unhealthy with the disease burden among adults now shifting to non-communicable conditions. Improvements in health and nutrition have been only marginal in the last two decades, leading to a dual challenge of a shifting disease burden and malnutrition in India. This blog gives a glimpse into the current health challenges facing adults in India.

A shifting disease burden and new challenges

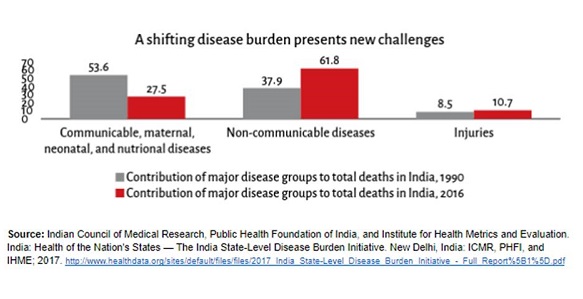

There are three main contributors to ill health – the first are communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases, the second encompasses non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and the third comprises injuries. Communicable diseases are spread through contact with infected people, contaminated objects, disease carrying insects, and through air and water. Diseases not caused by infectious agents or are non-transmissible are called non-communicable diseases (NCDs). For example, the flu is a communicable disease, while cancer is not.

In the last three decades, India has undergone an epidemiological transition – that is, the disease patterns have changed. Mortality due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases has decreased, but the contribution of NCDs to health loss and death has nearly doubled from 1990 to 2016.

Unfortunately, while NCDs are responsible for a majority of deaths, easily preventable diseases continue to haunt a large number of people resulting in a compounded disease burden. Diarrhoea, lower respiratory, and other common infectious diseases still contribute to approximately 1 deaths out of 6 in the country.

The Dual Burden of Malnutrition

As with diseases, India is also increasingly facing a dual burden of malnourishment: under-nourishment and over-nourishment. A useful measure to understand varying contributions of different ailments to the total losses suffered due to illness, is the disability-adjusted life year (DALY). It is a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability, or early death. What is telling is that the contribution of nutritional deficiencies to DALYs has increased between 1990 and 2016 in India, indicating that nutritional problems persist and require urgent action.

To get a sense of how healthy someone is, one can look at three different aspects of a person’s nutrition profile.

- Their body-mass index (BMI) (weight in kg divided by the square of height in metres);

- Their nutrient and calorific intake; and

- Their heights during adulthood.

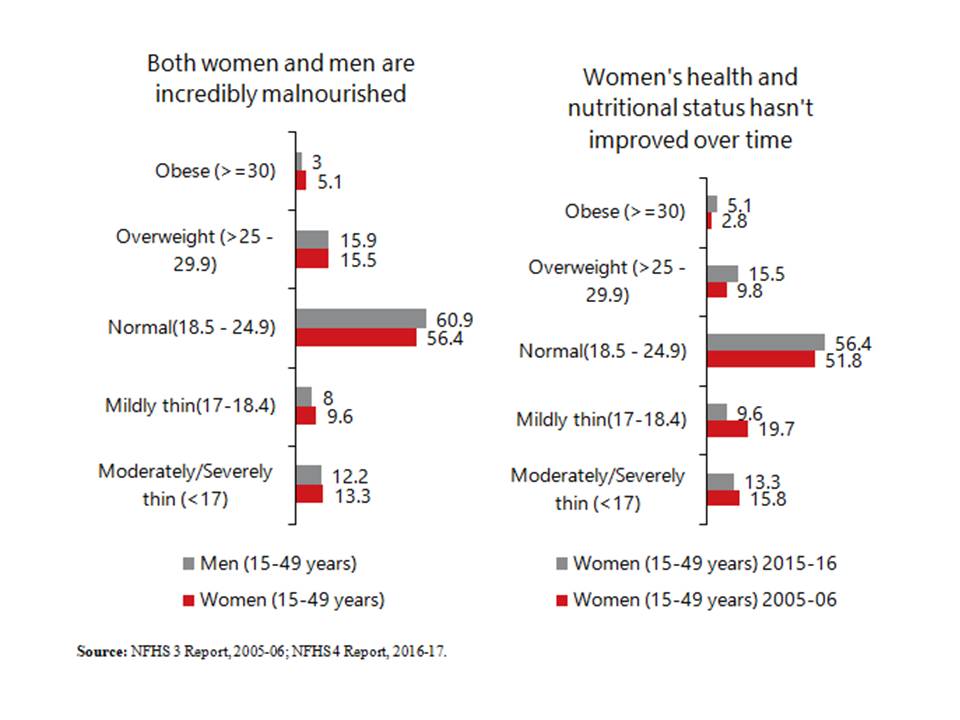

Measuring health through BMI suggests that approximately 4 in 10 people in the country are outside the ‘normal’ range: 2 out of 10 are thin, and 2 out of 10 are overweight. Between 2005-06 and 2015-16, the proportion of mildly thin women declined by 10 percentage points, but the proportion of severely thin women has only decreased minimally (2 percentage point decline). On the other end of the BMI spectrum, the percentage of overweight and obese women has increased as well. Similar trends can be observed for men as well. Moreover, NFHS-4 data shows that the very poor are likelier to be thinner than ideal (normal BMI range – 18.5 to 25), and the rich are likelier to be overweight.

adverse maternal outcomes and health risks for unborn children. This has likely contributed to the consistently demoralising state of child health in India. Therefore, while undernourishment has always been a problem, over-nourishment is rapidly emerging as source of alarm.

adverse maternal outcomes and health risks for unborn children. This has likely contributed to the consistently demoralising state of child health in India. Therefore, while undernourishment has always been a problem, over-nourishment is rapidly emerging as source of alarm.

Nutrient consumption has declined, despite incomes rising

Another useful measure to study the changing pattern of India’s health burden, is a look at consumption patterns, specifically the consumption of nutrients. In their article reviewing trends in food intake and nutrition in India, economists Jean Dreze and Angus Deaton point out that calorie consumption has been declining in rural areas. A calorie decline can be partly explained by a decline in calorie requirements due to economic development – such as mechanisation in agriculture, a drop in physically demanding tasks like carrying water over long distances, the emergence of sedentary jobs, etc.

The decline in calorie consumption seems acceptable, if calorie requirements have indeed declined. But the intake of proteins and other nutrients has declined too, with the exception of fat, revealed by the increase in the number of overweight and obese people.

The decline in proteins and other essential nutrients is particularly concerning, especially because this has occurred despite rising incomes, increasing per capita expenditure on food, and relatively stable prices– indicating that people are consuming fewer nutrients and calories per rupee spent, or that people are consuming more expensive nutrients and calories.

Gender biases exacerbate an already dire situation

Finally, the third indicator of long-term nutritional status of the population is to look at heights of adults. Taller populations are better-off, more productive, and live longer, according to various studies. Given the staggering amount of stunting during childhood in the country, it isn’t surprising that Indians are among the shortest people in the world, as Deaton points out. While Indians have been growing taller, Indian men have been doing so at more than three times the rate of Indian women. This suggests that nutritional gains have been unequally shared across men and women.

Inequalities between men and women, borne of patriarchal tendencies, highlight the fact that tackling this crisis is complicated. Inequality and subsequent distribution within the household is something that health programmes ought to focus on, and there is a need for a concerted effort to change the way people think about these things.

A shift in the disease burden comes against the backdrop of more people accessing private healthcare options due to an already weak public health system. These options are far costlier than government healthcare, and a large number of people have to shell out huge amounts of money, which pushes people further into poverty. Is the government spending enough? Is it reprioritising to account for the shift in the disease burden and current trends in malnutrition, and is it spending smartly? Do we have the public infrastructural capacity to deal with the diversity of health problems? And what would be the consequence for preventable health issues that can be easily dealt with – what policy makers like to call ‘low-hanging fruit’? While there is no straight answer, it seems the government has recognised the need for change in direction albeit not prioritised it. I take a closer look at this in my next blog.

Avani Kapur and Avantika Shrivastava contributed to this article.

The first part of this series can be found here.