What Municipalities Do: A Framework for Research

16 April 2021

This blog is part of a series unpacking the ‘PAISA for Municipalities‘ research which analysed urban local body finances in Tumakuru Smart City of Karnataka. The first part offers why the study was conducted, the backdrop to the study, and the researchers involved. It can be found here.

Any study of functional assignments to local governments begins with going through the legal provisions concerned with a fine-tooth comb. This is a task not meant for the impatient. The Karnataka Municipalities Act is a detailed legislation containing more than 400 sections. This Act was enacted in 1976, 18 years prior to the enactment of the 74th Constitutional Amendment and was not replaced by a new Act when the latter came into force. We had to wade through a legacy of outdated and repetitive provisions, as the law had accumulated amendments along the way.

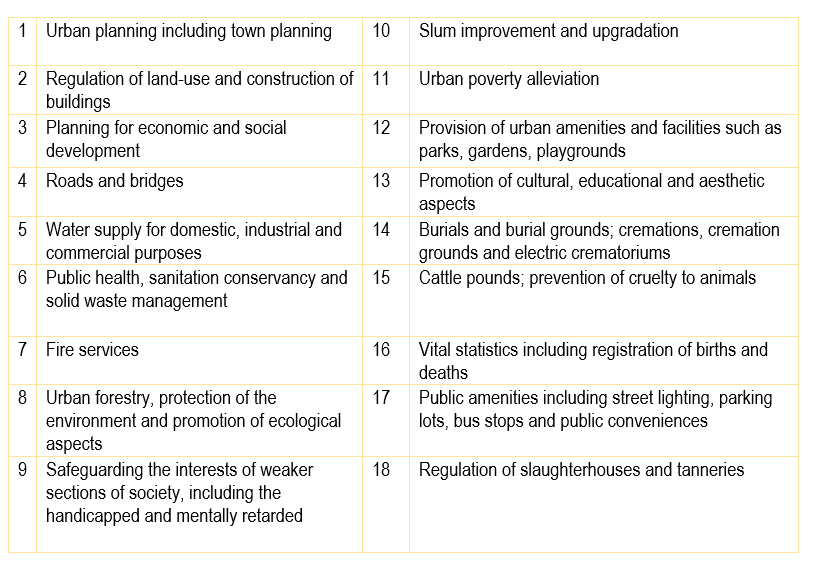

A simple thumb rule for undertaking functional assignment analysis in India, would be to start with the Constitutional provisions. Article 243W gives States the flexibility to endow Municipalities with powers and responsibilities which enable them to function as effective institutions of self-government. This is with respect to the preparation of plans for economic development and social justice; and the implementation of schemes entrusted to Municipalities. An illustrative list of the subjects to which these schemes could pertain is listed in the 12th Schedule of the Constitution. There are 18 subjects, as seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Matters listed in the Twelfth Schedule of the Constitution

We began with using these 18 matters as a template to classify the functions listed in the Karnataka Municipal Corporation Act. However, we realised that many sections in the law listed out overarching taxation and regulatory powers that spanned many subjects listed in the 12th Schedule. Therefore, we decided to add Taxation and Regulatory Matters as separate and distinct functions in themselves, whilst unbundling functions listed in the law.

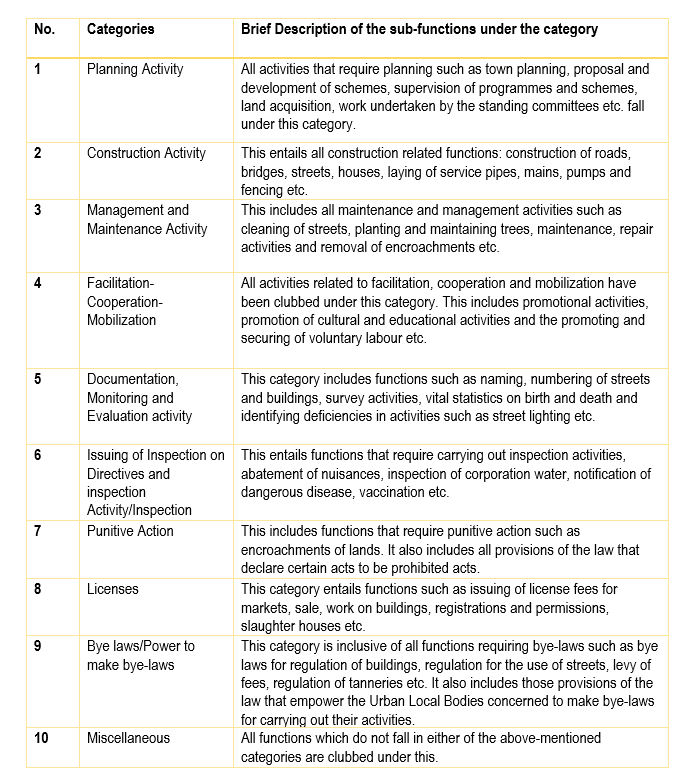

Then came the task of identifying functional categories or patterns, which cut across different sectoral areas. We identified 10 such cross-cutting activity categories, which are relevant and applicable to each of these matters (Table 2).

Table 2. Categories and sub-functions of activities

A grid was created, with functional sectors along the rows and functional categories along the columns, and each section of the law was read to allocate it to a box in the grid. It was a painstaking task, which my colleague Tanvi undertook with diligence.

At several junctures, we had to apply discretion while classifying activities under the most appropriate function. For example, where doubts arose as to whether a particular regulatory activity (such as imposition of fines, inspections etc.) should be classified under the relevant matter listed in the 12th Schedule or whether it should be classified under the generic function of regulation, a subjective assessment was made to determine under which function the activity fit most appropriately.

There would always be grey areas in such an approach, but the result was still useful, because it allowed us to step back and look at the larger pattern of the assignment of functions to Municipalities in Karnataka.

I shall describe our findings in my next blog.

T.R. Raghunandan is an Advisor at Accountability Initiative.

Also Listen To: Following the Money in Tumakuru Smart City