If a mere ranking of States on a scale of corruption doesn’t mean anything, what is the solution to the problem of measuring corruption? A check on some of the approaches adopted worldwide, reveal some interesting ideas.

The first thing about a good corruption measurement mechanism is that it is inclusive and collaborative. For example, EU’s anti-Corruption reporting mechanisms are managed by a Committee of Ministers, supported by a group of experts selected from a wide variety of backgrounds, including the public and private sectors, law enforcement and the judiciary. These experts are selected through an open and transparent call and act in their personal capacities. The Committee of Ministers is supported by a network of local research correspondents. Surveys are conducted among the general population in any member states every two years, and is based on face to face interviews, covering a sample of about one thousand respondents. There are individual country wise chapters and tailor made recommendations for each country. In addition, one particular sector, say, public procurement across different sectors of the economy, is targeted for thematic focus in each report. The surveys cover both perception and questions on personal experience with corruption.

Another approach is to interlink the measurement studies on corruption with other surveys. For example, one could compare happiness and quality of life with corruption. Transparency International and World Bank have conducted surveys that links control of corruption with indicators of government effectiveness. Similarly, one could link studies on corruption with indices that measure the extent of free and fair competition, or the ease of doing business. However, when linking surveys for different facets of governance with measurement of corruption surveys, one must take care to note that several of these indices use the same sources of information for their data analysis. In such circumstances, correlation between surveys is not advisable, as that would amount to double counting of the same indicator.

A third facet of measuring corruption, somewhat obliquely though, is to use data concerning enforcement of criminal laws against the corrupt. However, here too, data may be misleading. For example, if crime statistics show spikes of anti-corruption complaints and cases, it may not mean that corruption has increased. It may be a reflection of the efficiency of the judicial system rather than the prevalence of crime. Furthermore, the lack of complaints against corruption reflected in the judicial system may be a result of a lack of confidence of the people in whistleblower protection laws. One can overcome these sources of prejudice in research through different methodologies. Thus, for example, Transparency International studies go beyond crime and court prosecution statistics to look into the actual content of court cases; to understand who the passive and active actors are and in what contexts they are engaged in corrupt transactions. However, the moment one goes beyond quantitative indicators to qualitative ones, the methodology of the research becomes complex, increasing its costs in terms of money and time.

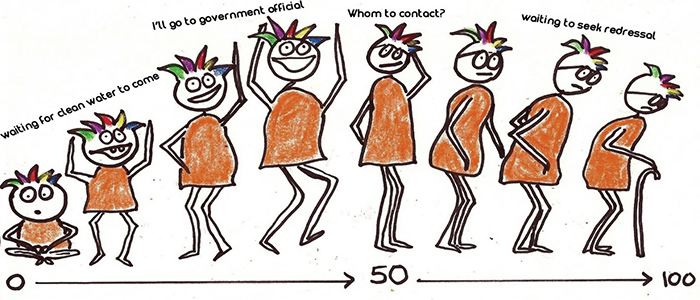

We then may be forced to take a second look at perception reports once more, namely, to use soft data to measure the social understanding of corruption. Such surveys are usually culture sensitive and may be misleading. I once heard a person who was experienced in conducting such surveys saying that if one asked people whether they would report instances of corruption, across the world they tend to largely reply in the affirmative, simply because (a) it is politically correct to say so, (b) concealing corruption may invite criminal action and (c) people want to say things that you want to hear. He said that in democracies that were till recently dictatorships, people also thought it was ‘wrong’ to report on others, because dictatorships had given a bad name to the habit of snitching on neighbours. Thus, a lot of people lie in surveys, about their involvement with and knowledge of the phenomenon of corruption. Nevertheless, it is important to pay care and attention to those who answer in the negative to such questions; that would be a measure of the lack of confidence of people in whistleblower protection arrangements.

Cutting across all methodologies, using surveys to measure corruption requires careful consideration of a series of methodological options. How one designs sampling is important; over representation of certain segments may give a distorted view of the problem. The placement of questions is important, because a wrong approach can mean a break in the train of thought of the one surveyed. Scaling of answers is important – a five point scale would invite a large set of people to seek to remain non-committed; in the centre of the scale. The length of the questionnaire and the type of survey procedure (face to face, email, and phone or internet based surveys) all can affect interest of the participant and veracity of the responses. Sadly, in practice, questionnaires are often copied and pasted from existing surveys, without developing and integrating a theoretical model underpinning the data collection process.