As with most other sectors, corruption in the health sector can be classified into two categories, petty corruption and grand corruption. In addition, there could be another category, namely, the widespread prevalence of unethical and abusive practices. Each is described below.

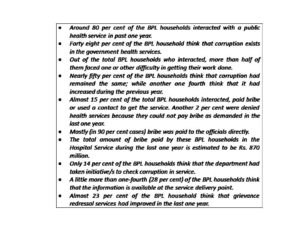

Petty corruption refers to relatively small amounts paid in order to get services that are either free, or subsidised. While these amounts might be individually small, they amount to a big burden because they are usually demanded of poor people.

The typical petty corruption related to the health sector that people experience are as follows:

- Bribes to gain access (to wards, to enter restricted areas such as labour wards)

- Bribes to jump queues, (out-patient department, laboratory sampling)

- Bribes to get free services (for X-ray, medicines, diet supplements)

- Bribes to get admission or discharge from the hospital, or to release bodies from the mortuary.

- Bribes to obtain certificates on medical condition, such as fitness certificates, disability certificates etc., which are required for various purposes such as foreign travel, professional recruitments etc.

Such bribes are usually picked up by the staff in medical institutions and doctors might not be directly involved (except in the case of the issue of medical certificates). However, the passing on of cuts to doctors might not be ruled out.

Grand Corruption relates to large volume corruption, often involving a team of officials, doctors, private sector agents and politicians. Instances of grand corruption in the health sector are:

- Procurement corruption (to win tenders for supply of pharmaceuticals, medical equipment and hospital supplies, civil construction or repair contracts). This can result in over-invoicing, supply of substandard equipment, supplies etc., sometimes having shorter life span or shelf life in case of medicines, over-supply of some items in excess of requirements. This might also result in excessive preference shown for one of the other brand of a drug, when cheaper generic (and equally effective) products are available.

- Corruption for postings and transfers of doctors and other staff to ‘lucrative’ positions, (where they have access to better private practice, more openings for diversion of medicines, or cultivation of influence).

- Corruption in certification of facilities and the provision of mandatory recognition of departments and medical colleges, following inspection.

- Corruption in admissions, examination marking and passing students in medical colleges, particularly in respect of specialty and super-specialty post-graduation courses.

An even more serious phenomenon is when grand corruption snowballs into increased petty corruption, because of artificial shortages, or more expensive medicines and other supplies, leading to a more bribes being paid for these at the customer interface level. Grand Corruption can also be integrated with petty corruption. Typically, this happens when profits from bribes taken at lower levels is shared up the ladder, through ‘pre-paid’ arrangements – a lump sum payment to secure a lucrative posting and regular monthly payments, collected from below, channelised upwards with a cut for everybody involved.

Other Unethical and Abusive practices:

Apart from the usually adopted classification of corruption into petty and Grand corruption, there is another category of corruption prevalent, which is in the nature of corrupt practices arising from the breach of the very same internal code of ethics that give doctors their credibility and status. I once held discussions a few years back with experts having a high moral foundation from a well-reputed health care institution in Bangalore. From this educative discussion, one pieced together some of these practices that are typically seen:

- Accepting percentages or gifts from other doctors, hospitals, laboratories, imaging centres, pharmacies, pharmaceutical companies and medical equipment companies for referring patients to them or using their products. Known as ‘cut’ practice, this is a widespread phenomenon, with both doctors and those who give them such gifts or percentage, not considering these to be bribery in any form.

- Suggesting unnecessary laboratory tests.

- Undertaking unnecessary treatments, such as Caesarians, when normal deliveries are possible.

Amongst doctors, there is very little understanding of the distinction between unethical and (corrupt) practices. There is a significant prevalence of unethical practices, with most doctors who indulge in these believing that these are not wrong at all. There is a group of doctors (probably a majority) who actually believe that there is nothing wrong with earning from kickbacks and cuts.

Unethical and monopolistic practices in the pharmaceutical business:

The pharmaceutical profession generates a large portion of the grand corruption seen in the health sector, largely because of extortionate and disproportional pricing of medicines beyond the raw material and production cost, in the name of covering R&D costs and IP protection and bribes in cash and kind paid to doctors for prescribing medicines.

Yet, in conclusion, it must be emphasised that many of these practices are certainly not considered to be ‘corruption’ within the strict framework of the law. For example, high prices by pharmaceutical companies are perfectly legal, even though one may call it a way to obtain windfall profits, through seductive advertising, cartelisation and ‘persuasion’ of doctors to prescribe such drugs. Furthermore, it is not as if all doctors are corrupt, if the strict definition of corruption to be an unacceptable act performed by a public servant is taken into consideration. Yet, there is a natural and moral understanding of the meaning of the word, ‘corruption’. Plenty of professional acts in the private sector, in the view of a reasonable man or woman, would certainly be considered as corruption.

In my next blog, I look at how such ‘grey areas’ of corruption may be tackled. I continue with my case study of the health sector.

This blog is part of a series. The first blog can be found here.