The 15th Finance Commission Report: What has Changed on Fund Transfers to States?

23 April 2021

On 1 February 2020, the 15th Finance Commission (FC) of India tabled its interim report. But the world was already changing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in a redesign of macroeconomic forecasting models around the globe. In India, as the pandemic took root in March 2020, Union and state governments soon struggled with the allocation of fiscal resources, since previous estimations of budgets were no longer valid. Weak revenue generation was a prime factor. By the time the FC submitted its final report in 2021, it too had to revise its economic outlook for the next five years.

Knowing about the changes is important because the FC is a very important body for Centre-state fiscal relations. The Union government has traditionally had more resource-raising powers while the state governments have, over the decades, become responsible for a higher share of development and welfare-oriented expenditure. The 15th Finance Commission has thus had to tread a fine balance on the centralisation of transfers versus the fiscal autonomy of states to meet states’ needs in the face of an unprecedented pandemic.

In the first blog of a series on recommendations, I will discuss the overall trends in resource transfers and compositional change introduced by the 15th Finance Commission in aggregate transfers [1], which is linked to the sharing of taxes by the Centre with the states.

What is the Finance Commission?

But, before we get into some of the new recommendations, it is worthwhile to understand the role of the Finance Commission.

The inadequacy of the states in resource raising powers vis-à-vis their expenditure responsibility was recognised by the Constitution of India, that laid out the principles of resource-sharing between the Centre and states. The particulars of the sharing pattern was vested in a Constitutional body – the Finance Commission [2]. (Finance Commissions are constituted every five years, and the most-recent one is the 15th Finance Commission.)

Specifically, the Finance Commission was made responsible for addressing fiscal imbalances that arise between i) the Union and state governments (known as vertical imbalance), as well as those that arise ii) across states (known as horizontal imbalance).

Broadly, the Finance Commission advises the Union government on the following:

- The distribution of resources between the Centre and states from the divisible pool of taxes.

- The principles of distributing grants-in-aid (GIA) to states, which are additional sums paid to states in need of assistance.

- The principles of transfers to local bodies of states, which include Gram Panchayats and Municipalities.

The resource-sharing architecture has undergone several changes. This evolution has partly been the result of a changed political reality. As India witnessed coalition governments at the Centre, state-level political parties slowly began to have more say in national policy. Also, economically, a growing mismatch between revenue resources and the quantum of expenditure between different levels of government also assisted in bringing about this change.

Trends in resource transfer to states

As a response to a widening vertical imbalance, the 14th Finance Commission (2015-16 to 2019-20) had recommended that states receive a share of 42 per cent of the divisible pool [3], increasing the previous Finance Commission’s recommendation by 10 percentage points (Report of the Fourteenth Finance Commission, 2015). (More on 14th Finance Commission recommendations can be found in this blog.)

This was a landmark decision at the time. The higher quantum of revenues dedicated to states changed the state resource envelope considerably. This was significant because tax devolution to states, in intergovernmental fiscal transfers (IGFT) parlance, is ‘untied’. This means that states are simply entitled to them without having to fulfil criteria set by the Centre. This creates more room for fiscal autonomy for states.

The 15th Finance Commission, however, has only marginally changed the share of taxes to states from 42 per cent to 41 per cent on account of the status of Jammu and Kashmir changing from a state to a Union Territory (Report of the Fifteenth Finance Commission, 2021).

The Finance Commission – which is also Constitutionally mandated to determine the quantum flow of select GIA to states – has recommended an increase in conditional transfers. These are ‘tied’ funds. States are eligible to them only upon fulfilling certain criteria. All conditional grants are meant to ‘nudge’ states towards best practices in public finance management, with a view towards fiscal prudence. However, conditional grants are also Centrally-dictated; states themselves cannot access these resources unless they comply with the mandate determined by the Centre. The fiscal autonomy of these grants is, therefore, comparatively limited to untied funds.

The GIA, as a share of total transfers has increased to 19.65 per cent of aggregate transfers while tax devolution comprises 80.35 per cent. In comparison, the 14th Finance Commission had recommended a sharing pattern of 11.97 per cent for GIA and 88.03 per cent for tax devolution out of the total aggregate transfers recommended. Therefore, a higher share of aggregate transfers are now tied funds.

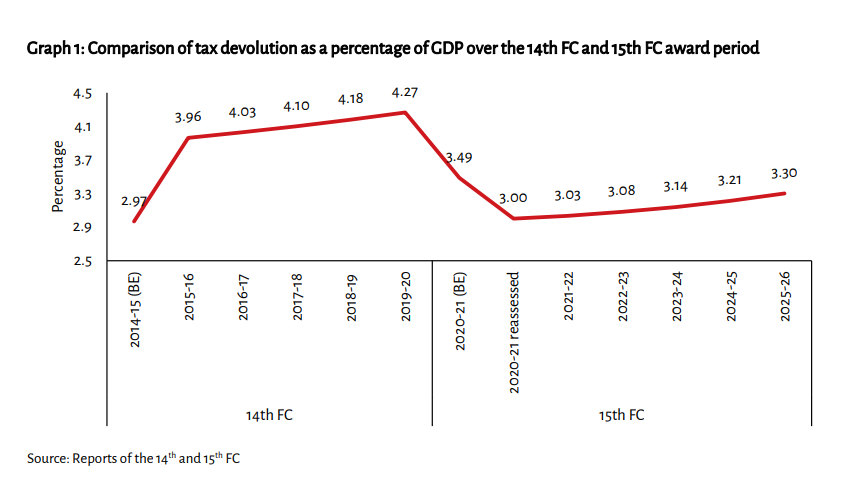

The average share of tax devolution as a percentage of GDP has also reduced from the 14th Finance Commission award period to the 15th Finance Commission award period. Total tax devolution to states in nominal terms has increased by 7 per cent from ₹39.5 lakh crore to ₹42.2 lakh crore. However, as a percentage of projected GDP (projections made by both FCs respectively), the share has gone down by one percentage point from 4.11 per cent to 3.15 per cent.

This reassessment has been done largely due to a weak revenue performance following the pandemic (more here). This indicates that, even though the actual value of tax devolution has increased, the growth in share of resources to states has not kept pace with the GDP.

Total tax devolution as a percentage of GDP in FY 2020-21 has also been revised from the Budget Estimates (BEs) of 2020-21 (refer to Graph 1). The reassessed share is 3 per cent for 2020-21. By the end of the 15th Finance Commission award period in FY 2025-26, it is estimated to go up to 3.3 per cent.

fincomindia

fincomindia

There are two things of note here. Firstly, the share of tax devolution is not even estimated to cross 2020-21 BEs even in the last year of the 15th Finance Commission award period. This indicates that the FC does not foresee a full-fledged recovery of revenues to pre-pandemic levels soon. Secondly, there is an increase in the share of conditional grants, but states can access these only when specific reforms are introduced.

While the share of conditional grants was equivalent to only 17 per cent of the total FC transfers under the 14th Finance Commission period, it has now increased to nearly 57 per cent of approved transfers under the 15th Finance Commission (Jayanta Roy, Aditi Nayar, 2021). This has led to a “compositional alteration”.

The new Finance Commission report has addressed this “compositional alteration”. Even though the experience of states with unconditional transfers has generally been more productive, it notes, the transfers are met only if Central taxes are buoyant. In other words, if the economy starts to do well and GDP increases, taxes are also swiftly generated. Fixing a certain share of the increasing taxes to states guarantees resources to state governments.

However, as per the 15th Finance Commission, taxes will not be as buoyant during the post-pandemic recovery period. At a time like this, “fixed absolute numbers” of conditional grants would be a comparatively more assured way of transferring financial resources to states (Report of the Fifteenth Finance Commission, 2021).

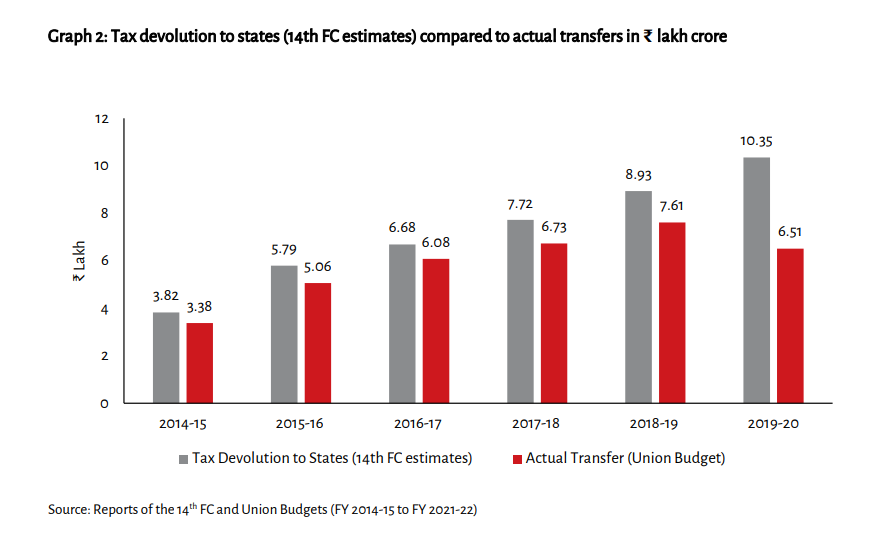

A comparison of the estimated tax share against the actual quantum of transfer over the award period of the 14th FC demonstrates the above point. From FY 2015-16 to FY 2019-20, the actual transfer was less than 17 per cent (on average) of the estimated devolution. In FY 2019-20 the decline was as much as 37 per cent in the face of lower than estimated generation of revenues and an economic slowdown at the time.

Meanwhile, states have been consistently arguing for more fiscal room (FirstPost, 2017). The new compositional change may further restrict the fiscal autonomy of states at a time they require it most.

Thus, even though the 14th Finance Commission recommendations changed the landscape of fiscal federalism in India with its landmark recommendations that would have increased state fiscal autonomy, statesfincomindia have had to adjust to resources that were much lower than estimated. This will most likely remain the case in the post-pandemic recovery period as tax revenues pick up, albeit slowly. As a result, the divisible pool of taxes may itself shrink due to lower than expected share of tax devolution despite the optimistic GDP growth estimates made by the 15th Finance Commission.

If states have less and less autonomy over their resources, then recovery from the pandemic, with very little fiscal room, will be very slow. Crucial spending on capital may suffer due to this, resulting in longer term disruptions to sub-national economic growth and higher inequality among states.

The next blog will explore another important set of recommendations that determine funds with states – those linked to the changes in the tax devolution formula.

Meghna is a Research Associate at Accountability Initiative.

[1] Aggregate transfers refer to the total resource transfer to states. It comprises: 1) Total tax devolution to states from the shareable pool of taxes, and 2) Total FC grants to states. As per the recommendations of the current FC, these grants include i) the revenue deficit grant, ii) disaster relief grant, iii) grants to local bodies, iv) state specific grants, and v) sector specific grants.

[2] Articles 280 and 281 of the Constitution provide for the setting up of Finance Commissions. Constitution of India: https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/COI_1.pdf.

[3] The divisible pool is that portion of gross tax revenue which is distributed between the Centre and the states. The divisible pool consists of all taxes, except surcharges and cesses levied for specific purpose, net of collection charges.

References

Report of the Fifteenth Finance Commission. (2021). Report of the Fifteenth Finance Commission. Retrieved from https://fincomindia.nic.in/ShowContent.aspx?uid1=3&uid2=0&uid3=0&uid4=0&uid5=0&uid6=0&uid7=0

Report of the Fourteenth Finance Commission. (2015). Report of the Fourteenth Finance Commission. Retrieve from

https://fincomindia.nic.in/writereaddata/html_en_files/oldcommission_html/fincom14/others/14thFCReport.pdf

Firstpost. (2017, November 29). Finance Commission to look into tied grants for states: A nudge strategy by govt after loan waivers or a U-turn? Retrieved from Firstpost: https://www.firstpost.com/business/finance-commission-to-look-into-tied-grants-for-states-a-nudge-strategy-by-govt-after-loan-waivers-or-a-u-turn-4233135.html

Jayanta Roy, Aditi Nayar. (2021, February 23). The Indian Express. Retrieved from The Indian Express: https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/fifteenth-finance-commission-has-increased-proportion-of-grants-conditional-on-reforms-by-states-7200026/