The Status of Gender Budgeting in India

10 February 2023

The blog was initially published on 23 December 2021 and has been updated with Budget 2023 data.

In 2005, India started releasing a gender budget along with its Union budget. The gender budget is an exercise that applies a gendered-lens to the allocation and tracking of public funds. The focus is on improving women’s welfare through government policies [1]. But a look at data reveals that, even now, the gender budgeting exercise faces issues, and that gender budgets are still away from realising this objective.

Before considering the gender budgeting exercise, it is first important to look at budget allocations. For FY 2023-24, the total allocation for Gender Responsive Budgeting (GRB) increased by a mere 2 per cent from the Revised Estimates (RE) of FY 2022-23.

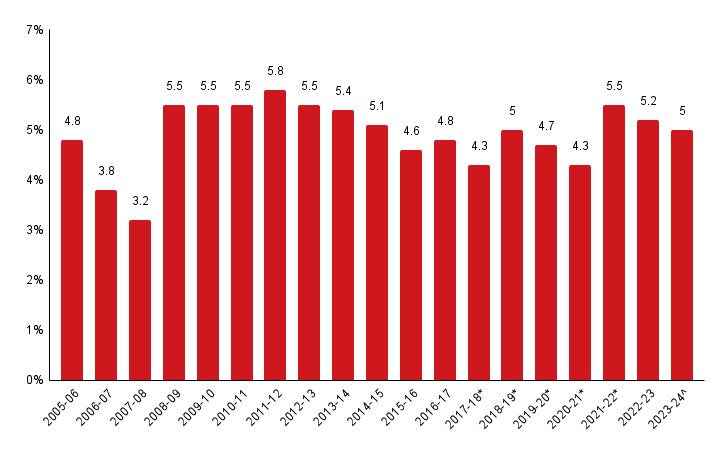

The allocation to gender budgets in India as a proportion of the total Union budget has remained constant since its inception, ranging from around 3 to 6 per cent of the Union budget [2]. For FY 2023-24, the total allocation for Gender Responsive Budgeting (GRB) increased by a mere 2 per cent from the Revised Estimates (RE) [a] of FY 2022-23. In recent years, the actual allocation to gender budget as a proportion of the union budget peaked in the pandemic in FY 2021-22. However, it has been falling since then. In FY 2022-23, the RE of gender budget accounted for 5.2 per cent of the Union Budget. For FY 2023-24, the Budget Estimate (BE) [b] of the Gender Budget accounts for just 5 per cent of the total Union Budget.

Figure 1: Allocation to Gender Budget as a Proportion of the Union Budget Fell From 5.2% (2022-23) to 5% (2023-24)

Note: All figures are Revised Estimates, except figures marked with * which are Actuals, and ^ which are Budget Estimates.

Skewed Composition

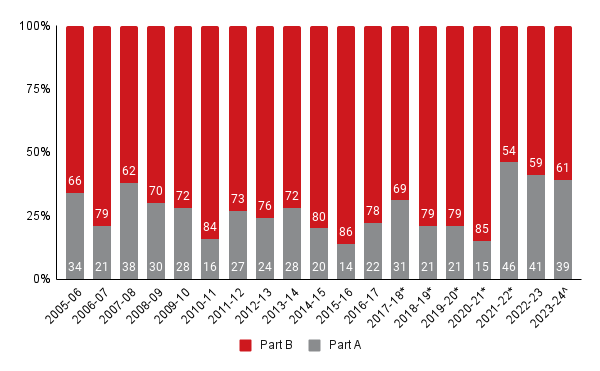

The gender budget in India comprises two parts: Part A encompasses schemes that allot 100 per cent of the funds for women (such as maternity benefits). Part B consists of schemes that allocate at least 30 per cent of funds for women (such as the Mid-Day Meal scheme). Since its initiation, the gender budget has increasingly been dominated by Part B [3].

As seen in Figure 2, in FY 2005-06, Part A and Part B accounted for over 34 per cent and 65 per cent of the GRB. Since its inception however, the Gender Budget is skewed by allocations in Part B, with Part B occupying 85 per cent of the gender budget in the pandemic in FY 2020-21.

In FY 2021-22, the share of Part A in the total Gender Budget peaked at 46 per cent, for the first time. However, since, it has been falling. In FY 2022-23, Part A accounted for 41 per cent of the gender budget while Part B accounted for 59 per cent. In FY 2023-24, however, Part A, went further down to 39 per cent, while Part B increased to about 61 per cent of India’s gender-responsive budget. This implies wholly-women-specific schemes do not form the majority of the gender budget as of now.

Figure 2: Allocations to Part A and Part B as a Proportion of Gender Budget

Note: All figures are Revised Estimates, except figures marked with * which are Actuals, and ^ which are Budget Estimates.

Key Concerns

It is also important to note some systemic issues on gender budgeting in India. The first is the basis on which schemes are included or excluded.

Firstly, the gender budget does not take into account some of the major schemes that benefit women. For instance, the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) aims to provide household tap connections to all rural households by 2024. Tap water can particularly improve women’s [c] quality of life because it is mostly women and girls who gather water in households that do not have regular water access [4]. Yet, none of the allocations in the JJM have been reported in the gender budget [5].

The present segregation into parts A (100 per cent) and B (30 to 99 per cent) also means that schemes that earmark less than 30 per cent of their funds for women are excluded from the gender budget. The way schemes allocate at least 30 per cent of their funds for women also seems unclear.

For instance, the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana – Gramin (PMAY-G) accounted for 24 per cent of the gender budget in 2023-24 and was placed in Part A of the GRB because the scheme encourages houses to be owned by women and thereby might benefit women. On the other hand, only 27 per cent of the funds allocated under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) accounted for Part B of the GRB, despite women being 55 per cent of MGNREGS workers [6].

In terms of methodology, lack of a transparent mechanism that details weights attributable to various schemes for furthering gender equality [7] could be one explanation for this paradoxical allocation, wherein a scheme that evidentially targets and benefits women (MGNREGS) is placed in Part B, while gender-neutral scheme, is placed in Part A.

The gender budgeting exercise thus does not seem to fully take into account prevailing gender dimensions as they play out in society, and leaves space for errors. Additionally, the lack of gender-segregated data leaves a gaping hole for an effective GRB. Reporting allocations in Part B, specifically, becomes difficult in the absence of such data [8]. This is why some scholars have pointed out that the entire process has become an aggregation exercise [9] more than a potent tool.

Ria Kasliwal is a Research Associate at the Accountability Initiative.

References:

[1] Gender Budget, Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India.

[2] Gender Budget, Union Expenditure Profile for FY 2005-06 to FY 2023-24.

[3] Gender Budget, Union Expenditure Profile for FY 2005-06 to FY 2023-24.

[4] Press Release on Jal Jeevan Mission: during lockdown by Ministry of Jal Shakti dated 2 July 2020.

[5] Scheme Guideline on Jal Jeevan Mission by Ministry of Jal Shakti, 2010.

[6] Gender Budget, Union Expenditure Profile for FY 2021-22.

Notes:

[a] Revised Estimates (RE) are estimates of projected amounts of government receipts and expenditure until the end of the financial year.

[b] Budget Estimates (BE) are budget allocations announced at the beginning of each financial year.

[c] This was stated in scheme guideline document as well as press releases.

Also Read: Under-prioritisation of Women’s Safety in the Union Budget?

I came looking to understand if the Budget announcement of opening 157 Nursing Colleges – where approx 80% of staff and students will be women was included in your analysis . Hope to hear more about it in the future. Concerned that 10 Crore non-recurring Budget per CON sounds too little esp if hostels and classes need to be constructed.