Under-prioritisation of Women’s Safety in the Union Budget?

8 March 2022

In 2021, the National Commission for Women (NCW) registered a 30 per cent increase in the number of complaints related to crimes against women in India from 2020. Of this, the greatest proportion comprised cases of emotional abuse, followed by domestic violence, and harassment for dowry. India has various schemes for women’s safety, but a look at the funding status of key schemes and even their categorisation, reveals gaps.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) recognises that gender-based violence is a public and private phenomenon. It impacts women’s right to mobility and comprehensive well-being and empowerment. In 2015, for example, the MWCD initiated the One Stop Centre (OSC) scheme, which provides a range of services – from emergency redressal to shelter and psychosocial and legal counselling – under a common roof. Similarly, the Women Helpline Scheme (WHS), integrated with the OSC, allows women affected by violence to seek appropriate redressal measures. Schemes like Ujjawala[1] attempt to intervene at the community level to prevent trafficking and sexual exploitation of women and girls. Swadhar Greh (SG)[2], Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP)[3], Mahila Police Volunteers[4], among others, aim to prevent gender-based violence and provide rehabilitation to its victims, and attempt at making community spaces safe for women.

Thus, what seems counterintuitive is that the Government of India (GoI), under the MWCD, spends marginally on women’s safety. In this year’s Union Budget, the budgeted (or estimated) expenditure on the MWCD is ₹25,172.28 crores, which is 0.6 per cent of the overall budget. The government has allocated ₹3,184.11 crores on women’s protection and empowerment measures, which includes women’s safety, accounting for only 0.08 per cent of the ministry’s overall budget.

Reclassification of MWCD’s key schemes complicates prioritisation

Before diving into the funding status, it is important to understand the ministry’s categorisation of schemes linked with women’s safety. In 2021-22, MWCD streamlined its Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) under three umbrella schemes of Mission Poshan 2.0, Mission Shakti, and Mission Vatsalya. Under its erstwhile classification, schemes related to women’s safety like the OSC, Ujjawala, and SG, featured as standalone schemes under the Mission for Protection and Empowerment of Women. Now, reclassified under the Mission Shakti, these schemes have been clubbed under Mission Shakti’s sub-schemes of Sambal and Samarthya for achieving the objectives of safety and security, and empowerment of women, respectively.

Sambal comprises schemes such as the OSC, WHS, BBBP, etc. Samarthya, on the other hand, consists of Ujjawala, SG, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY), among others. As a consequence of this reclassification, there seems to be a dilution of what the government interprets as women’s safety. For example, the PMMVY, a maternity benefit programme previously under the Umbrella Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), is now a part of Samarthya. But, at the same time, schemes such as Ujjawala and Swadhar Greh, which focus on gender-based violence and women’s safety are also a part of Samarthya.

Fund allocation for Mission Shakti in this year’s budget is dismal

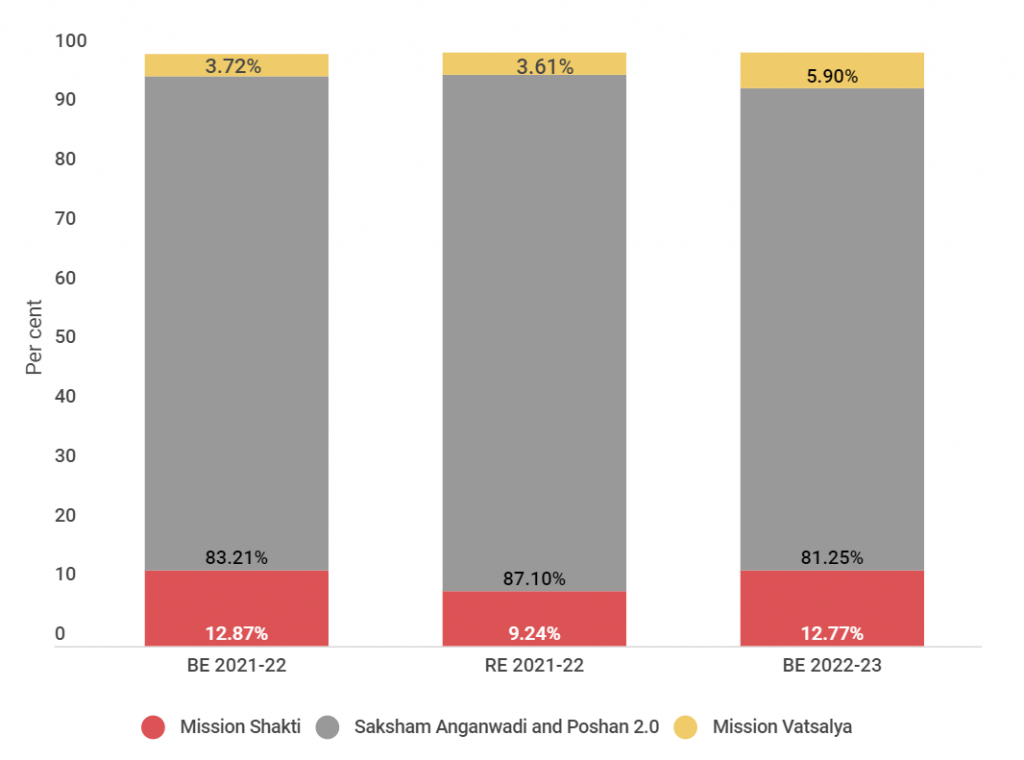

Zooming back out, in financial year (FY) 2022-23, allocations for Mission Shakti have marginally increased by 0.02 per cent, as a proportion of MWCD’s CSS outlay, from Budget Estimates (BE) 2021-22. Allocations for Mission Shakti are exceedingly small, especially compared to Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 (Figure 1). On the other hand, Mission Vatsalya, which comprises only one scheme – the Child Protection Services (CPS) – has seen an approximately 2 per cent increase in its proportional share. Both Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 and Mission Vatsalya are schemes related to women and children but do not exclusively look at women’s safety.

Additionally, schemes that do focus on women’s safety, such as those under Sambal, constituted only 17.65 per cent out of the total funds earmarked for Mission Shakti, decreasing by approximately 1 per cent from BE 2021-22. The decline in prioritisation for Sambal schemes was also observed in 2021-22, as allocations were 10 per cent less than the standalone allocations made under each of these schemes (OSC, WHS, etc.), respectively, the previous year.

Figure 1: Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 received the most prioritisation out of the total MWCD CSS outlay in FY 2022-23

Prioritisation in the Gender Budget

The Gender Budget (or GB) is another way to capture the government’s emphasis on reducing crimes against women. Created in 2005, the GB has been a regular budgetary exercise at the Union level to allocate a specific proportion of scheme-related funds exclusively for women. Part A of the GB reflects a 100 per cent scheme allocation for women. Part B, on the other hand, reflects 30 per cent of the scheme benefits for women. In the case of the MWCD, Part B received approximately four times more allocation than schemes in Part A in BE 2022-23.

All Sambal schemes feature under Part A. In 2022-23, allocations for Sambal schemes reduced by 1 percentage point to 16.81 per cent of the overall allocation under Part A of the MWCD’s GB. However, schemes under Samarthya (Ujjawala, SG, PMMVY, etc.) received the most prioritisation at approximately 76 per cent. Further, a minuscule percentage of Samarthya schemes are also allocated under Part B of the GB.

As mentioned above, schemes under Sambal and Samarthya appeared as standalone schemes in the GBs before FY 2021-22. A comparison of the composition of a few schemes under Part A of MWCD’s Gender Budget (Figure 2) suggests that while the proportional share of OSC had increased marginally from 2018 to 2020, the overall share of schemes – WHS, BBBP, Ujjawala, and SG – meant for women’s safety and empowerment remained low.

Figure 2: Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) forms the greatest proportion of Part A of MWCD’s Gender Budget among the selected schemes

![Figure 2: Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY)[8] forms the greatest proportion of Part A of MWCD’s Gender Budget among the selected schemes](https://accountabilityindia.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/image_2022-03-07_140702-1024x923.png)

Other ministries/departments also complicate allocating for women’s safety in their GBs. A previous blog reflected on some of the challenges associated with the lack of transparency in GB allocations. Schemes to strengthen women’s safety, such as those by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), have stopped featuring in the GB statement altogether. Additionally, existing schemes for women, such as the Crime against women – Juvenile Justice Human Rights of the Policy Department and the Scheme for Safety of Women on Public Road Transport of the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, feature in Part B of the GB statement.

A lot is yet to be done

In a previous series of blogs, T.R. Raghunandan highlighted the “inter-relatedness” of crimes against women, which warrants action in an integrated approach. To an extent, the Nirbhaya Fund[5] solicits action from ministries/departments, and state governments, to implement projects and schemes to prevent and redress crimes against women and promote women’s safety in India.

In the next blog, I will trace the challenges to the utilisation of funds for key women safety schemes – OSC, WHS, BBBP, and others – over the years and across ministries/departments and state governments, and what this might mean amidst the reclassification exercise of the MWCD.

Tanya Rana is a research intern at the Accountability Initiative.

NOTES

[1] Ujjawala is short for “Ujjawala: A Comprehensive Scheme for Prevention of Trafficking and Rescue, Rehabilitation and Re-Integration of Victims of Trafficking for Commercial Sexual Exploitation”.

[2] Swadhar Greh seeks to provide institutional support to women in difficult circumstances, providing relief and shelter, legal aid and counselling, vocational and skill training, etc.

[3] Beti Bachao Beti Padhao seeks to address (and reduce) sex-selective abortions, and promote the girl child’s survival, protection, and education.

[4] Mahila Police Volunteers have been envisaged to create a safe space for victims of gender-based violence to report crimes and seek necessary redressal. Like Women Helpline, this scheme is also integrated with the One Stop Centre.

[5] This non-lapsable fund was set up in the aftermath of the 2012 Nirbhaya rape case. MWCD, as the nodal ministry, is responsible for monitoring any schemes or projects sanctioned against this fund.